“Panorama of the City of Interzone. Opening bars of East St. Louis Toodleoo … at times loud and clear then faint and intermittent like music down a windy street…. The room seems to shake and vibrate with motion…”

That was how William S Burroughs introduced the world to the ‘Interzone’ in his heroin-and-hashish-soaked 1959 novel ‘Naked Lunch’. Those few bars of Duke Ellington were just the beginning. Rarely has a writer had as much of an impact on rock’n’roll as Burroughs, who was born 100 years ago today on 5 February 1914.

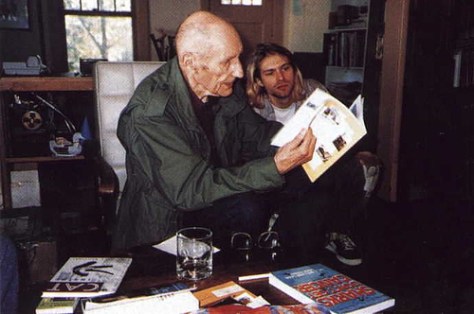

Kurt Cobain was such a big fan that he played discordant guitar on a spoken-word performance called ‘The “Priest” They Called Him’. The Beatles put him on the Sgt. Pepper’s sleeve. Jagger and Richards used his ‘cut-up’ technique of rearranging words from their notes to help them write lyrics for ‘Exile On Main St.’s ‘Casino Boogie’.

While Burroughs lived all over the world, including in London and in Tangier, in north Morocco, the city that inspired ‘Interzone’, he is perhaps most associated with the New York scene that he inhabited with fellow poets and writers like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. In later life, these writers became icons to the city’s burgeoning punk rock scene, particularly songwriters like Lou Reed, Patti Smith and Richard Hell.

Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore moved to New York as a teenager to become a part of this scene. I spoke to him about his memories of the author as an old man:

What was your first impression of Burroughs?

I used to live near him in New York City. I first moved to New York in ’77 and he was living in ‘The Bunker’ in the Bowery, which was a sort of mythological place that John Giorno, the poet, resided in. Burroughs lived downstairs from him, underneath the street. I would see Burroughs walking around sometimes in the Bowery. You saw all those cats walking around at that time: Allen Ginsberg lived down the street from me with Peter Orlovsky. I would see them holding hands on the subway, which was fascinating. It was more of a small town in New York City in those days. Everybody knew each other. You would see all the people who were celebrated in that scene, such as those guys, and then the punk rock people like Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell and Patti Smith. Everybody lived in sort of the same area. There was this little village, and the area was starting to draw attention to itself because of CBGB.

Was he going to the shows?

When I first saw William Burroughs he was sitting in the audience at CBGB when Patti Smith was playing. It was really interesting, because usually that club was just crammed full of kids my age, 19 or 20 years old. I remember going to see Patti Smith there, late 76 or early 77, and she was pretty much at her apex at that point. I remember the place being really crowded, and in the day CBGB had tables and chairs and they served hamburgers and there were dogs walking around. I don’t think it was really set up to deal with the capacity crowds that started coming in there. They got rid of the tables and chairs after a while, but they still had them then. I remember it being jam-packed and sitting tightly up against this little round wooden table, and all of a sudden people who worked there came into the middle of the room and just started yelling, pulling people out of the chairs and pushing people away. They slammed down a table right in the middle of the room and threw some chairs around it. Everybody was really upset while this was going on. Then they escorted William Burroughs and a couple of his friends in and sat them down very diplomatically at this table. I remember sitting there thinking: ‘Oh my God, it’s like William Burroughs’. He was this old, grey eminence in a tie and a fedora. He sat there and looked around at us. He didn’t seem to feel very guilty about taking up all this space. Then Patti came out in leather trousers and absolutely decimated the place. I remember that was probably the most fabulous Patti Smith performance I ever saw. She was on fire, knowing that William Burroughs was sat right in the middle of the room watching this concert.

When I first saw William Burroughs he was sitting in the audience at CBGB when Patti Smith was playing. It was really interesting, because usually that club was just crammed full of kids my age, 19 or 20 years old. I remember going to see Patti Smith there, late 76 or early 77, and she was pretty much at her apex at that point. I remember the place being really crowded, and in the day CBGB had tables and chairs and they served hamburgers and there were dogs walking around. I don’t think it was really set up to deal with the capacity crowds that started coming in there. They got rid of the tables and chairs after a while, but they still had them then. I remember it being jam-packed and sitting tightly up against this little round wooden table, and all of a sudden people who worked there came into the middle of the room and just started yelling, pulling people out of the chairs and pushing people away. They slammed down a table right in the middle of the room and threw some chairs around it. Everybody was really upset while this was going on. Then they escorted William Burroughs and a couple of his friends in and sat them down very diplomatically at this table. I remember sitting there thinking: ‘Oh my God, it’s like William Burroughs’. He was this old, grey eminence in a tie and a fedora. He sat there and looked around at us. He didn’t seem to feel very guilty about taking up all this space. Then Patti came out in leather trousers and absolutely decimated the place. I remember that was probably the most fabulous Patti Smith performance I ever saw. She was on fire, knowing that William Burroughs was sat right in the middle of the room watching this concert.

There was another club downtown called The Mudd Club. I started going there and you’d never know what was going to happen. There were no flyers or anything. Sometimes it would be a band or some performance art or a poet or whatever. One of the first times I walked in there they set up a folding card table onstage and William Burroughs did a reading. He did it a few times during those first few years of The Mudd Club, 78-79. That was fabulous. It was a very neighbourhood thing, and he was really acerbic. Cutting and biting.

Around that time they had the Nova Convention, which was one of the first celebrations of William S Burroughs. John Giorno instigated it. There were things that happened all over the city but there was a main concert which I got tickets for. There was a cavalcade of people announced for it: Patti Smith, Frank Zappa, Keith Richards, Brion Gysin and all the literary people. Everybody was there, except Keith Richards never showed up. Much to the audience’s dismay, because I think he sold a lot of tickets! We were all excited to see what that was all about because it was purported that Keith Richards wrote the lyrics to ‘Satisfaction’ after reading William Burroughs. It was a great event, and that was the first real gracing of William Burroughs as a cultural icon. That was a wonderful thing.

Did you meet him?

I didn’t meet him until he moved away. He relocated to Lawrence, Kansas and Sonic Youth was on a little miniature tour opening up for REM. REM were playing huge arenas and Sonic Youth would come out and the audience would sit there confounded. That happened all through the tour. It happened that we were in Kansas and James Grauerholz, who was his assistant/confidante/lover was a Sonic Youth fan. He was also possibly an REM fan, and Michael Stipe certainly moved in literary circles. He was a huge Patti Smith fanatic, as we both were, although she had disappeared from the scene at that point. She had married Fred Smith and to all intents and purposes she had vanished from the culture as an active presence. So we got this invite from Grauerholz for REM and Sonic Youth to visit Burroughs. So we went and that’s where we met him. I always remember walking into his little house in Lawrence, Kansas, which was one of these houses that Sears Roebuck had sold during the Fifties as Do-It-Yourself build-your-own house deals. It was quite interesting. He was extremely welcoming. He was elderly. He had magazines and books everywhere about knives and guns. That was a little off-putting. I didn’t know what to think of that because that was the last thing I was interested in. I tried to engage him in conversation: ‘So you’re obviously really into knives and guns?’ I asked him if he had a collection and I think he said yes. I asked him if he had a Beretta and he said: ‘Ah, that’s a ladies’ pocket-purse gun. I like guns that shoot and knives that cut.’ He was pretty sweet. I remember Michael Stipe had a hat on and he was going to toss it down. William thought he was going to toss it on the bed so he said: ‘No, no, no, don’t throw it on the bed!’ He really believed in these superstitions. I always remember that, even though of course Michael said: ‘I was never going to throw it on the bed. That was not my intention.’ Anyway, we had a nice visit with him. We visited his Wilhelm Reich orgone machine in the back yard. I sat in it and it was full of cobwebs.

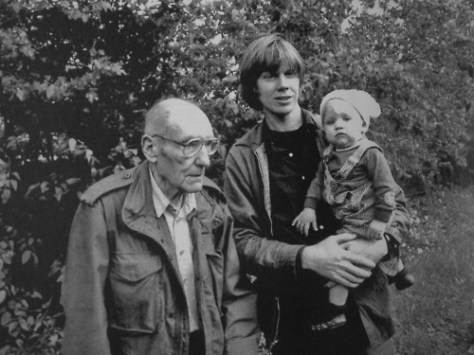

Sonic Youth went back independently a few years later. It was right after Kurt Cobain had died. They’d done that recording together. I always remember William talking to me about it. He had this look in his eye like: ‘Why would anybody take their own life?’ He couldn’t make sense of it. Why would you do that? Why would you disturb your energy and your cosmic soul like that? You don’t do that. You protect it. You have to fight for it. You can do whatever you like, you can take heroin your entire life, you can be an alcoholic or you can be a creep, but you don’t eradicate yourself. You don’t kill yourself purposefully. He had this look on his face that was very childlike. He was questioning why anyone’s psychology would take them there? I said, ‘I don’t know, but I think some people get overwhelmed by their own bio-chemical, depressive feelings. They feel like they can’t take it. They get really lost. It’s nothing we can intellectualise.’ That was interesting. We talked. My daughter was in her first year, I remember. She was starting to make some noise in the house while he was talking. She was in my arms and she was whining. He put his hand up towards her face. I thought: ‘Uh oh! I need to stand tall here’ but basically he just did this little hand movement and she immediately quieted up. It was like this magician’s hand movement. He was a father. His son died tragically while he was still alive. I think William dealt with a lot of personal horrors of intimacy, with his wife, his son and his own personal and sexual feelings.

How much impact did his work have?

He was very radical to me as a writer. I first read about him in rock’n’roll publications, especially Creem Magazine in the early Seventies when Lester Bangs was the editor. He would talk about William Burroughs in conjunction with Lou Reed or the Velvet Underground, and certainly Patti Smith would reference William Burroughs. Right around 73 or 74 I started reading him. I read it as prose poetry. There’d be these repetitive lines that would be added to rat-a-tat-tat. He had this American gangster kind of language. It was very curious and intriguing, and it was very musical, what he wrote. It was somewhat like reading Kerouac. He had a complete knowledge of literature but also a disregard for regulations.

Did he influence your own songwriting?

I think he influenced me. I think that describing things that were horrific, but transforming them into romantic notions, I think it was that. I think I was probably more inspired by people he had inspired. Certainly writers like Patti Smith, Lou Reed, Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell. Even John Lydon was influenced by him. Characters like Johnny Yen. I think certainly Iggy Pop was very inspired by Burroughs. Those songs on ‘Lust For Life’ and ‘The Idiot’. Then journalists like Richard Meltzer and Lester Bangs.

At the Nova Convention he read this poem that he introduced by saying it had been inspired by a trip to London. He had this whole connection to the London underground of radical poetry, people like Jeff Nuttall. Then he was also publishing pieces for men’s magazines like Mayfair. He was living on Drury Lane and being part of the scene around the Indica Bookstore that Barry Miles had. He was a big part of the London scene, hanging out with Ian Sommerville, Iain Sinclair and all those guys. London was a big part of his history. For me now living in London it’s something I really relate to, Burroughs’ time here, as an American in London. I remember at this reading he said: ‘There’s a rock’n’roll group in London called the Sex Pistols who have a song called ‘God Save The Queen’. I’ve written my own song. It’s called ‘Bugger The Queen’. It was a really anti-authority, anti-royalty and anti-privilege piece of writing. It was wonderful, because a lot of people in New York, a lot of Americans, don’t really have much consciousness about royalty at all. It’s this funny thing that happens in the rest of the world that happens in Walt Disney films. It has no effect in any cultural way. The whole audience was chanting the phrase ‘Bugger The Queen’ every time he said it. ‘Bugger The Queen!’ I’ve always wanted to record that song, but I don’t want to get thrown out of the country now I live in England.

I think the idea of writing under the influence of genuine vision, and to be locked away with your typewriter and just let it roll like that, will always make him an influence on new artists. I think his influence continues, and certainly with this centennial this year it seems that lots of people are interested in representing different aspects of William Burroughs’ life, here in London, New York and Boulder, Colorado. That’s where NaropaUniversity is, where he taught and where I lecture every summer. This year I’ll be doing a course a which focuses on Burroughs’ relationship to rock music. There’s a real relationship there. There are bands who named themselves after his writing. Soft Machine. Matching Mole, which comes from the French for Soft Machine. Even punk bands like Dead Fingers Talk. Iggy Pop singing songs like ‘Here comes Johnny Yen again’. Even the phrase ‘heavy metal’ comes from his ‘heavy metal kids’, which is something Lester Bangs brought into the lexicon of rock’n’roll. I talk about all that, and any music that is trying to exhibit ‘Burroughsian’ ideas. We look at what that means. It comes out of the fall-out of ‘hippy’ and utopian desires and all this kind of thing. There’s a kind of anger and it takes the piss out of this dream of utopia. It’s somewhat naïve to the powers of the establishment, which is where people like McClaren and the Pistols and The Clash started to come in. For any of us coming in at that point that was what we had to do if you had any interest in defining yourself. He was really central to that, and Allen Ginsberg as well.

He interviewed Jimmy Page for Crawdaddy magazine. Page was into mysticism and Aleister Crowley’s writing. Burroughs was certainly interested in metaphysics and outer space. He was very interested in life beyond the human realm. He was very interested in Scientology as well. He researched all this stuff. I don’t think he was a cultist, because I think he probably took that line that he wouldn’t want to belong to any group that would have him as a member.

Did you use his ‘cut-up’ technique?

The cut-up process was definitely something I used, and I do that not only with literary language but with music as well. You’re working traditionally with verses and choruses and bridges, but something I’ve always been interested in is what happens if you take things and move them around. In a way, that was always the modus operandi of Sonic Youth. There was always talk of Sonic Youth being this experimental band in terms of guitars or other things, but actually the most experimental thing about the band was song structure. How we took traditional song structure and would try techniques with it. One of those techniques was certainly that cut-up technique. I would certainly do that with lyrics. I would take pieces from different notebooks and I would cut them up to create new meanings, or a new unity. I always liked that. I think it was really successful. I thought it was really interesting when I read an interview with Jagger talking about doing that on ‘Exile on Main Street’. He found it to be a successful strategy for lyric writing.

An abridged version of this interview appeared in NME, 8 February 2014 under the headline ‘The beat goes on’.

‘It’s got lust and love and danger and jealousy on it. It feels “red”.’ Sadly, Katy B is not talking about the Big Red pizza bus where we’re sat in Deptford. She’s describing her second album ‘Little Red’, the follow-up to her rave-igniting, Mercury Prize-nominated 2011 debut ‘On a Mission’. After digging in to a rocket-loaded Giardiniera pizza, the south London R&B icon opens up about dating, dancing and her past life as Peckham’s answer to Vinnie Jones.

‘It’s got lust and love and danger and jealousy on it. It feels “red”.’ Sadly, Katy B is not talking about the Big Red pizza bus where we’re sat in Deptford. She’s describing her second album ‘Little Red’, the follow-up to her rave-igniting, Mercury Prize-nominated 2011 debut ‘On a Mission’. After digging in to a rocket-loaded Giardiniera pizza, the south London R&B icon opens up about dating, dancing and her past life as Peckham’s answer to Vinnie Jones.

NME Radar Artist Of The Week, 7 December 2013:

NME Radar Artist Of The Week, 7 December 2013:

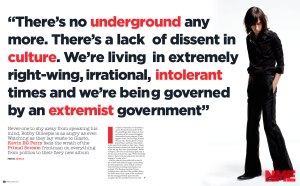

Up on the roof of the studio after the photo shoot, the 38-year old – whose well-worn passport reads Mathangi Maya Arulpragasam – has changed into an oversized t-shirt bearing a kitsch Hindu print. She stands 5’5’’ in flat shoes but her presence is immediate. Maybe it’s that she’s talking sixteen-to-the-dozen. She riffs like Wikipedia incarnate, following ideas down rabbit holes like a kid with a short attention span who’s just discovered hyper-links. She laughs a lot. It’s a conspiratorial laugh, as if you’ve just caught her doing something she shouldn’t be and she’s trusting you not to call the police. Right now she’s curled over a laptop, pulling up Google Images to illustrate how she stumbled across the ideas that would inform ‘Matangi’, her fourth record. The one the record label didn’t get. The one they delayed and delayed because Maya hadn’t delivered what they expected.

Up on the roof of the studio after the photo shoot, the 38-year old – whose well-worn passport reads Mathangi Maya Arulpragasam – has changed into an oversized t-shirt bearing a kitsch Hindu print. She stands 5’5’’ in flat shoes but her presence is immediate. Maybe it’s that she’s talking sixteen-to-the-dozen. She riffs like Wikipedia incarnate, following ideas down rabbit holes like a kid with a short attention span who’s just discovered hyper-links. She laughs a lot. It’s a conspiratorial laugh, as if you’ve just caught her doing something she shouldn’t be and she’s trusting you not to call the police. Right now she’s curled over a laptop, pulling up Google Images to illustrate how she stumbled across the ideas that would inform ‘Matangi’, her fourth record. The one the record label didn’t get. The one they delayed and delayed because Maya hadn’t delivered what they expected.

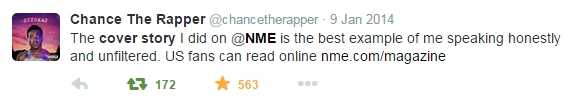

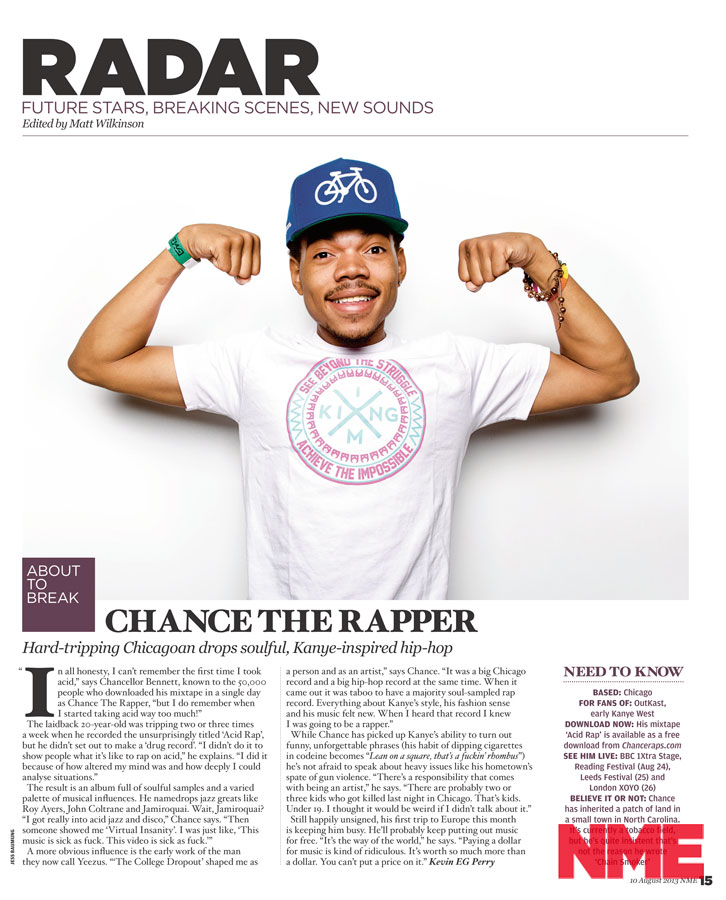

“In all honesty, I can’t remember the first time I took acid,” says Chancellor Bennett, known to the 50,000 people who downloaded his mixtape in a single day as Chance The Rapper, “but I do remember when I started taking acid way too much!”

“In all honesty, I can’t remember the first time I took acid,” says Chancellor Bennett, known to the 50,000 people who downloaded his mixtape in a single day as Chance The Rapper, “but I do remember when I started taking acid way too much!”

NME: Millions of people will be watching Glastonbury on primetime TV and it’s a become a social fixture. It might have started as a hippy, alternative festival, but it’s now the mainstream, isn’t it?

NME: Millions of people will be watching Glastonbury on primetime TV and it’s a become a social fixture. It might have started as a hippy, alternative festival, but it’s now the mainstream, isn’t it?