Part 1: Beginnings

I was watching Björk play the Other Stage at Glastonbury in 2007 when the dreadlocked man in front of me took a live snake out of his backpack. “Jesus!” I said, “Is that a live snake?” The serpent danced slowly in his hands, flicking out its tongue inquisitively as Björk’s rhythms filled the air. The man looked back at me with a distant smile: “He loves the vibrations.”

Well, don’t we all? Over the last two decades Björk’s vibrations have established her as pop music’s preeminent innovator, a fearless and restless proponent of the avant-garde whose discography defies the staid categorisation of genre. When I meet her on a summer afternoon in West London her enthusiasm for her work is infectious and the ebullient conversation as eclectic as you’d expect. We talk about education, about feminism and Lady Gaga’s outfits, about why she’s like ‘carrot soup and tequila’ and Coldplay are like ‘chips and sausages’, about political activism and aluminium mining and even about the lack of punk spirit in proprietary software, a topic she acknowledges she probably shouldn’t talk about.

Fittingly for someone who can make even reptiles shimmy, she also talks about the passion for nature which informed her latest wildly ambitious project, which shares its name with the hypothesis that humans have an innate affinity with the natural world: Biophilia.

It’s an idea she relates to. We’re in Little Venice, where she has kept a house since the time of Debut, and she tells me that the canals here are her surrogate for the sea: “Yeah, when I came here in ’93 I looked first for places by the Thames, but I didn’t really find anything I liked. Maybe it was a bit industrial, too. I guess I settled for the canals, I just like walking…”

This is a nicer place to walk than down by the river. “Yeah, I have a routine where I will go for walks and I can work on my melodies. I actually use the canals, but then I discovered because I go to the swimming pool in Westbourne Grove that I can walk through – there’s all these tunnels underneath the motorway. They’re quite good for working on my melodies actually. They’ve got a really nice echo. I sort of have to go somewhere where no one is, or they’ll arrest me and put me away.” She giggles. “In Iceland, even though you’re in the capital you can always walk for five minutes and you’re on your own. That’s kinda how I’ve worked on my melodies since I was a kid.”

The evidence for this is there in her songs: she says they’re all 83 BPM because that’s the speed she walks at. “Yeah, it’s pretty pathetic!” she laughs, “I’m actually trying to push one of the songs on the album now above 100 BPM but it’s proving hard!”

When Björk says she’s been working on melodies since she was a kid, she means it. She first became a star in Iceland at the age of 11 after one of her music teachers sent a recording of her singing a cover of ‘I Love to Love’ by Tina Charles to RÚV, at the time Iceland’s only radio station. When the recording was broadcast Björk was offered her first contract by local label Fálkinn, and with the help of her stepfather released a self-titled album in 1977. Björk has since said that she felt strange receiving praise for songs she had only sung, not written, although she did contribute one track which showcased her precocious talent and her maverick aspirations: an instrumental piece for flute named after Icelandic painter Jóhannes Kjarval.

She didn’t remain that cherubic child for long. As a teenager she shaved her eyebrows and joined a series of punk bands: she drummed for an all-girl group called Spit & Snot, was flautist for the proggier Exodus and then joined Tappi Tikarrass, whose name translates as ‘Cork the Bitch’s Ass’. Her next band, KUKL, recorded a couple of albums for Crass Records before spawning The Sugarcubes, whose 1988 single ‘Birthday’ and subsequent album Life’s Too Good gave Björk her first real taste of global acclaim.

After three albums The Sugarcubes split in 1992 and Björk moved to London to establish herself as a solo artist. She made it look effortless. The album she recorded with producer Nellee Hooper of Soul II Soul, Debut, won her ‘Best Newcomer’ and ‘Best International Female’ at the Brits in 1994, while her music videos were already beginning to make her an icon: the Michel Gondry-directed video for ‘Human Behavior’ was nominated for a Grammy.

For 1995’s follow-up Post she worked with an assortment of producers drawn from jungle and trip hop, including Tricky and Graham Massey of 808 State, to create an album she described as “musically promiscuous”. 1997’s Homogenic reacted against this, setting out to explore her Icelandic identity against a backdrop of explosive, distorted beats. Her next album Vespertine was another about turn. When it was released in 2001 she told Simon Reynolds that she wanted it to be “a love affair to the home, about creating paradise under the kitchen table. It’s about creating peaks without outside stimulants… The kind of peaks you reach reading a book.”

Looking back at her career, Björk acknowledges that the clearest pattern is her stubborn refusal to repeat herself. She offers by way of explanation the fact that she adores a challenge, which often manifests itself in her choosing to take on genres she ordinarily dislikes. She wasn’t sure about a cappella music, she says, so she made Medúlla. She wasn’t excited by protest music, so she made Volta . “I guess with each project I have some sort of personal taboo I have to break,” she continues. “I don’t know why. It’s some sort of a kick I get out of it. I mean, obviously I’m also embracing a lot of things that I like, like nature, electronic music, vocals, choirs…”

For Biophilia, which will be simultaneously released as a series of musical and educational games built into an app for iPad and iPhone, part of the challenge was to take the idea of generative music, music created by a system, and use it to actually write great music: “I guess I’ve been going to galleries and museums – not often, but once in a while – and I’ve always thought it was such a strange brand of music. A lot of it is such a good idea, an amazing concept, and you walk through it and it’s interactive in space – but would you be able to then go home and listen to that song on your stereo, without knowing that, and it still be a good song? Or hear it on the radio? In most cases, that’s not the case. I don’t blame it; because of course it’s still good. Certain music is good in films, certain music is good in porn movies, certain music is good in clubs… that’s the good thing about music, it’s everywhere. I guess my challenge with this project was to do generative music but that it was still ‘songs’. I gave it my best shot that if in ten years somebody listens to the CD, or whatever format is going on then, and they don’t know anything about it… it would be just like my other CDs. It wouldn’t be that you needed the apps to get it. So in that way I wanted to unite those two worlds, you know?”

Part 2: Biophilia

Björk‘s new project Biophilia does not want for ambition. It has been billed as the first ‘app album’: Each of its ten tracks are being released alongside a corresponding app version for iPad and iPhone. These apps can be bought and accessed through the central Biophilia app, which appears as a galaxy waiting to be explored and navigated, with the songs as stars in its constellation. Zeroing in on a star enables you to hear the song as Björk recorded it, or to play a game which will involve you manipulating the music in some thematically-appropriate way. For example, on ‘Virus’ you play the part of a cell defending itself from viral attack, while on ‘Thunderbolt’ you draw Tesla coil charges which alter the bass lines you hear.

I’d been playing with the apps before we met and while they all seemed intuitive at the time, my notebook ended up covered in a bewildering cobweb of ideas: something about ‘continental drift’, something else about ‘seduction’, something about ‘DNA’, something else about ‘piano keys’. I look at Björk helplessly. Can she put it into words? “In a way, every app is a visualisation of the song. You are inside the song,” she explains eagerly. “I think when you listen to music on headphones and you close your eyes it’s very… internal. I wanted it to be that you could see the sounds, you know?”

Her career has already given us a series of beautiful and intensely original music videos, so I ask whether that experience of working with directors helped to inform her design work with the app developers? One immediate obvious difference is that she’s not onscreen for the apps: “With all the video directors I’ve worked with in the past I’ve always had just a couple of clues about each song: ‘This one is about walking on roofs’ or ‘This one is confrontational’ or ‘No, it’s not pink’. I’ll have a few clues about each song, and then I will try and work with them and try and bridge that gap between the image and the sound. But I mean I think this is even better, for me. For me it was never really about the way I look.”

I have to stop her there. This is a woman who wore a swan to the Oscars, whose dress at the Olympics in 2004 unwrapped itself to reveal a 10,000 square foot map of the world, and who, more immediately, is currently sat opposite me beneath a copper dome of hair that blossoms around her ears in the shape of a bell. She’s one of the most iconic pop stars in the world. It must, I suggest, have been a little bit about the way she looked. She laughs. “Yeah, of course it is, but it’s really about the core, and the core of it to me is the song. I guess I learned after being in bands for fifteen years before I did my solo stuff, and we were punks and we were like: ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter how things look it’s all about how they sound’ and then somebody would just take a picture of us and put us in the papers and you would be upset – not that it was ugly, nothing to do with vanity – just that it didn’t fit the music. So I guess I had fifteen years of kinda…” she shrugs indifferently, “and then once every few years I would meet somebody who totally got it. So I learned, almost like I was a pupil. So for fifteen years I learned that if you match the right image to the right sound it makes my life a lot easier! But I think it has changed as I get older and become more idiosyncratic with the music – like, I used to collaborate more but now in the studio I make all the decisions!”

You’re an auteur now? “Yeah, yeah, yeah! I’m bossy! I’m a bossy-boots!” She laughs. “Well to be honest it’s mostly me and the engineer so there’s no one to boss around anyway, but I’ve kinda managed to develop more so I know more what I want there, so by the time I work with the visual people, or the app people, or the photographers, it’s like I’m back in a band. It’s like ‘Oh!’ You all sit in a circle and say: ‘How about crystals?’ ‘How about this?’ So it’s more like being in a band. So I enjoy the process, in that way.”

What struck me when I played with the apps was how immersed you become in the music and in the myriad ways that your actions could affect it. In an age where music seems to have been devalued by its sheer ubiquity, these apps demand your full attention. Was that the aim? “Hmm… that’s a good question.” She pauses to think, and when Björk is thinking she does this thing where she rotates her jaw as if chewing distractedly. “To be honest, I wasn’t focused on that but maybe unconsciously! I can’t promise you totally… my focus was kinda more on the fact that we had the touch-screen. We were performing on it on the Voltatour from 2006 to 2008 and all I could see was opportunities. The thing I was more conscious about was how I was unsatisfied with my music education in school. I mean obviously there were a lot of amazing things. I was there for ten years and I loved it, don’t get me wrong, but I felt it wasn’t tactile enough. It was more ‘booksy’ or, I don’t know what you say in English? Like ‘academic’?”

‘Didactic’, I suggest? “Yeah! So because I had such strong feelings about musicology, and about how I see rhythms.” She laughs. “Well, I said it there, didn’t I? How I see rhythms, and how I see different chords and different scales and different speeds, and what I feel like at the beginning of a song, when I go inside and when I come out the other end. I wanted to include that somehow, and I kept thinking: ‘For kids’. I guess because I spent three years on trying to get it as true to how I feel about music as possible, I could say ‘yes’ to your question and say I wanted other people to be able to see it too. But to be honest I wasn’t so much thinking of that because two years into the project I didn’t know that it would come out on touch-screens because they hadn’t even made iPads! I was mostly writing it for our touch-screens, we had Laniers. I was making programs: ‘The structure of this song is crystals, so it’s this shape. Let’s write a program that’s like that.’ Then I’d sing about it and put the emotion in there as well, so for me it was trying to connect things which very often are not connected and I feel they should be, you know?”

She’s overflowing with excitement about the project now: “In my mind I was trying to simplify something but I guess it comes across as being the most complicated project I’ve ever done! I think it is in print, but I think once you sit down and play with the apps it’s something like… ‘Oh! You go three times round the galaxy and then you tap on something and then lightning comes at you’… it’s very hard to describe in print, because basically then you’re making it didactic again, when you write about it! Basically this project, to cut a really long story short, is about making things that I feel have been too didactic into a 3D tactile experience. You know, you take up the spoon and you get to turn it in circles.” She picks up an empty coffee mug and whisks a tea spoon inside it. “The other idea is to do with electronic music, because I love electronic music. I’ve been doing it for a very long time, but it had its limitations and one of the criticisms I’ve heard for twenty years from people who prefer indie music or classical music or jazz or whatever is that they’ll be like: ‘Yes, but it has no soul’ and I’ve been doing that debate for twenty years now!” She laughs. “It’s like, well, it’s because nobody put it there!”

So this album is not just about bringing together music, technology and nature, it’s also about putting the soul into electronic music? “Yeah, and with the touch screens now you’re not stuck with a grid. That’s why the songs are like they are. The grid is water. The grid is a pendulum. The grid is DNA multiplying. It’s not 4/4. It’s not TCK-CH, TCK-CH, TCK-CH, TCK-CH. It’s basically liberating you from the grid, but it’s still electronic music.”

Björk’s quest to give electronic music a soul reminds me of a contrary attempt by Coldplay to use a machine to help their drummer sound less like a machine. In a recent New Yorker article by Burkhard Bilger about a study into time perception by neuroscientist David Eagleman, Coldplay’s Will Champion describes how the band had been using a click track when playing live to keep time but then, having found that playing to it made them sound too rigid, the band decided not to do away with it but to speed it up and slow it down in places to artificially recreate the mood of a live gig. Coldplay now use elaborate “tempo maps” for their live shows and, as Champion told the magazine: “It re-creates the excitement of a track that’s not so rigid.”

As I describe how uncomfortable the idea of Coldplay’s tempo map makes me, Björk is nodding furiously: “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.” It seems strange to me, I tell her, that a machine is actually helping them to sound human. “It’s a really interesting point, because obviously I’ve been doing gigs since Debut and I’ve tried to solve this riddle ten times! It’s like the tenth time I’ve tried to solve this same riddle, in a way, but I just get better tools now! I mean, I personally would not have gone about it that way, because I feel you should let the tools be good at what they are good at. It’s not that the tools are pretending to be human or that the humans are pretending to be tools. Then again, I’m a very different musician to Coldplay. I like extremes. I think they probably like the middle a bit better than I do.”

Björk: queen of the understatement. She smiles. “I’m not saying that as a bad thing, you know? I quite enjoy a fierce techno beat with a pipe organ, do you know what I mean? I like that contrast, you know? Some people don’t. It’s kinda like having carrot soup and tequila, not just chips and sausages.” She laughs. “So I quite enjoy that. I mean the way I’ve done it in the past, what I’ve found really helpful, is if you solve this riddle in a few different ways in each concert, and then you never have songs back-to-back that are solved the same way. That puts the musicians on their toes. Say for example, on the Post tour: I had an accordion player who could play like Beethoven, he was a virtuoso accordion player and he played all the string arrangements but he was playing on a grid… so you had something very human, that no machine could do, and then you had something that only a machine could do. The next song, it would be electronic samples, very techno or whatever, played by a drummer not on a grid. He would be playing that and then I would be singing on top of that, you know?”

So varying the use of click-tracks or grids is your way of keeping things fresh? “Yeah. On one song the accordion player would just press ‘play’ on a computer and you’ll have a beat that doesn’t vary in speed. It’s just like a grid. Then you have a virtuoso musician do something that only a human can do. The next song would be a totally different approach, where again you would have electronic sounds that are very electronic – they’re not pretending to be acoustic – but they’d be played by a drummer so they wouldn’t be on a grid, or on a clock, and then you have musicians playing along with that. Then the next song would be just me and a keyboard, and then the next song would be everything on a grid. In that way, things can be dynamic. It keeps people on their toes. I’ve been in bands where nothing is on a grid and that can also, funnily enough, become stagnated. It brings different things out in people if you do that, but I think life is like that, anyway, and nature is like that. You can have something very grid-like such as your calendar, or your heartbeat, but you have to work around it. Aging, for example. It’s not dynamic. You’re not 10, and then you’re 50, and then 5. It’s a grid that you have to work around. You might as well just let it be very ‘griddy’ and then bring something that’s the opposite and… spunk it up!” She collapses into a fit of giggles. “I don’t know what word to use!”

Another example of throwing opposites together is the fact that the electronic sounds the Biophilia apps make are based on a series of acoustic instruments, many of which she had built specifically for this project: “Basically, I kept thinking of the kids. So, I wanted them to have a touch-screen, to have access to an algorithm from nature, to be able to play it with one finger and then for it to be connected with either a pipe-organ, or gamaleste, or pendulum, or sharpsichord. It’s sort of like ‘Where is the electric?’ and ‘Where is the acoustic?’ You make the machine do what the machine is best at doing, which is those algorithms that nobody could do live without it and then you can make impulsive decisions depending on your feelings at the time, or your emotions, and react to that – but then that’s plugged with acoustic sounds. I kept thinking about how kids sometimes get too stuck into computer games and I wanted it to not just be this virtual world where everything’s perfect. I wanted to be connected with things which are more like the skin or oxygen. So basically the pipe-organ is like wind, and the gamaleste is like bronze and the pendulum is like gravity. I just think that age between five and seven is magical. You can learn new languages, you can learn to read and write, you’re just a sponge. So whatever you grasp on the world in those years usually stays with you for the rest of your life.”

Was it important then that there was a element of composition built into the app, as well as creating a new way to present your own music? “Very much so, but I understood that it would just be an introduction. I call it ‘semi-educational’ because if you wanted to take the ‘semi-’ off you’d have to do a lot of work and a proper program. But it’s sort of an introduction, the 101 of musicology, but obviously this is my point of view: how I see musicology, so the songs will sound a little bit like my songs. Hopefully it will inspire people to go off and do their own songs.”

Part 3: Bootlegs

As intriguing as Björk’s Biophilia project is, there’s something about it that makes me feel slightly uneasy. I think it’s to do with the number of times the names ‘iPad’ and ‘iPhone’ appear on my press release and particularly with the fact that the Biophilia apps will not be made available on any other format. For someone as fiercely independent as Björk, who has spent her entire career on indie labels, this seems out of character. I hate to think of Björk as a corporate shill, but as we all know deep down in the depths of our iSouls, Apple have now unquestionably become The Man.

So this is what I ask her: ‘You’ve talked about the iPad feeling like a return to a punk ethos, where anyone can use it to make their own music. At the same time, iPads are expensive and elitist gadgets. Do you think there is a discord between the technology and the spirit of what you’re trying to do?’

“Yeah, for sure, there’s definitely another polarity there, a conflict,” she replies. “The only solution for me was to somehow be some sort of a ‘Kofi Annan’ and try and make these two worlds speak to each other.”

She pauses and coyly drums her fingers on the table.

“I’m not supposed to say this, probably, but I’m trusting that the pirates out there won’t tie their hands behind their back.”

‘So you’d quite like to see Biophilia end up on other operating systems?’

“Yeah. I mean, I’ve been in Africa in the last few years, and Indonesia. There are people there who have cardboard houses but they have mobile phones. Everybody’s texting. It’s just a question of time before touch screens are cheap. That’s why we really made sure when we wrote all the programs that they will transfer to other systems. I mean, I don’t totally understand technologically what it is that makes that possible.”

Björk, as she mentioned, should probably not have said that. It seemed to me at the time that she was being disarmingly honest, and also perhaps a little knowingly provocative, so I quoted her in the news story we ran when the interview took place in July. The story was quickly picked up by Wired, then Pitchfork and NME and then pretty much every other music magazine with a net connection. Unfortunately but inevitably the time-worn journalistic credo of “simplify and exaggerate” kicked in a little more with each new article, with the result that by the time her thoughts had made it to, say, Billboard, they had become simply a reductive instruction: ‘Björk: Hack My Apps!’

In the interests of clarity then, here’s the message that appeared on Björk’s Facebook page the following day: “been doing scrillions of interviews , most has gone well except, i noticed a misunderstanding online when asked in an interview if i thought hackers would get into the app box i answered something along the lines that that was to be expected . that you could trust that they wouldnt have their hands tied behind their backs . i have seen this then juxtaposed against other things i said later to make it look like i am encouraging them. this is not how i feel.”

Interestingly, that message itself disappeared a day after it was posted without explanation. It’s understandable, of course, that she does not want to see a project she’s invested so much time and energy in being bootlegged. This is without mentioning the huge amount of her own money that she’s poured into Biophilia, of which more later. Ultimately it’s likely that the point is moot anyway: transferring an iPhone app to another operating system presents significantly more technological hurdles than pirating an MP3.

The subtext here is the broader question of how musicians are going to get paid for the work they do, now that we have apparently decided, as a society, that we’re cool with getting our music for free, either through streaming services like Spotify or through illegal means. The result is that making a great album is no longer enough: musicians are having to find new ways to persuade us to actually part with our cash. There have been missteps. Indeed, Björk herself started to get a reputation for unnecessarily repackaging and reissuing her music around the time of 2006’s Surrounded box set, and she’s currently selling something called Biophilia: The Ultimate Edition from her website which will set you back a cool £500. There doesn’t seem to be room for egalitarianism in the brave new world that the internet has created, but at least with the apps she has created something original and of real value.

However, I get the impression from talking to Björk that her work on Biophilia is not born out of a desire to sell a gimmick, but out of a genuine desire to create something innovative despite the baffled state of the music industry. Unfortunately for her, and for her fans, being in the technological vanguard tends to come with an accompanying high startup cost. Hence her involvement with Apple and the grim shop-front reality that as influential as Björk is, she couldn’t have even dreamed of getting something like this off the ground without being certain that she could count on the support of the iTunes Store. What her comments really tell us is that Björk is still struggling with the same dilemma being faced by countless contemporary artists across a whole range of mediums: do you want your art to be enjoyed by as many people as possible, or do you want to earn a living?

For Björk, it was her work with cutting-edge app developers which really recalled her punk days: “I guess when I was talking about ‘punk’ I was more talking about the way the app team worked together. By then we had no money, we’d run out of budget. It’s like two years since we ran out of budget. The app team said ‘We wanna do this so much that we’ll do it for free, but then we’ll split the profit 50/50. That’s kinda how we used to do things, the indie companies back in the punk days. Everyone makes the posters and glues them up and hand-makes the covers and then if there’s profit you just split it 50/50. That’s kinda what I meant by ‘punk’.”

The flexibility offered by the apps opens up the possibility of releasing further songs into the Biophilia universe: “I’m hoping I can do that. I’m at least thinking ‘double album’. We’ve got ten songs, maybe I can keep adding another ten. I don’t know, I’m just going to improvise. The good thing about the internet, or should be, is that it’s more spontaneous. I feel like if we’re making a new model it should be more flexible. But I mean, I wrote almost all of the songs on this album on touch-screens. That was a really new thing to me. The first time I’m not writing songs by walking outside and singing, because I had it in my lap and could faff about and improvise. A couple of songs were written on Nintendo games controllers. The chords we made on the touch-screens I would put on so that we could control the chords and the speeds and the time-signatures like a computer game. Both because I was trying to think of something that kids know, and also after programming with a mouse for ten years… it’s not really helpful for making quick decisions. I haven’t even tried it because I know it’s not a turn-on for me, to be singing like ‘dner-dner-d-ner-ner’ and then going on the mouse,” she mimes clicking and dragging, “clicking and opening up new boxes. It’s just not… it’s good for… is it the left-side of your brain? The more sort-of essay-writing side… but if you’re writing a song it needs to be more tactile. So far, with computers or electronic stuff, this is the most… you can grab it…” she mimes moulding clay, “or act really quickly and be more impulsive, so that’s kinda why we’ve be doing stuff with that.”

Björk believes children will respond instinctively to this tactile world: “I’ve wanted to do a music school since I was a kid, and so I was thinking well maybe it wasn’t that literal. I always imagined myself on some farm in Iceland, an elderly lady, and all the kids with recorders or whatever coming for a few weeks. I was always thinking about those few years, between five and seven, when it was more of an introduction to music, and for this to be an inspiring and enabling thing. For me to see the touch-screens and realise how everybody’s downloading the ocarina, so that this could mean that a kid in India could learn the difference between scales or time signatures, and not by reading this thick book but just through feeling, just by playing with it for a bit. I saw my own daughter, who’s eight now, playing with an app called ‘The Elements’ which is basically the element table. There’s also another one called ‘Solar System’. The teams that made those two apps actually did a couple of things for me. But with ‘Solar System’, she’d just been playing and scrolling with the solar system, and I think she gets more what the solar system is from that than I did from five years of lessons! I think these things are meant to be known more like that. They’re not like Latin or something, where you have to spend years and years over details and grammar. It’s more of a feeling.”

So you want to teach the world to sing? “I don’t know. I think everybody, once in their lifetime, wants to have a go at sharing what helped you… I was laughing about it with my friends. ‘Oh my God, what am I doing?’ This project is about the universe and everything! It’s vast! But I think it’s something I’ve noticed with people my age, because obviously I take care of my kids, but now I’m just about getting to that age where I’m starting to take care of my parents as well. It’s sort of a debate. ‘When will I start having the Christmas parties?’ It’s not yet kicked in, but give it five years. It’s a really strange feeling, because I’ve always thought of myself as the one who attends the Christmas parties. It’s interesting that age, about 50 or something, that you are in the middle, so you take care of both sides.”

The album also seems to reflect an almost spiritual awe that comes from contemplating the intricacies of our universe, recalling the work of the cosmologist Carl Sagan. Is she becoming more spiritual as she gets older? “I think so! I never thought I would… When I was a teenager, or in my twenties, I thought stuff like that was really pretentious, but now if I can teach you something…” She laughs. “Now that I’m not twenty any more, I think it’s natural for each individual, at least once in their life, to want to put out their version of how they see the world and how it could function. For me, obviously, I’m obsessed with music, so my musicology… nature is my religion, in a way, and I see sound as celebration of that. It’s a bit…” She pauses as she searches for the right phrase, “a bit ‘over-the-top’ to say that!” She smiles indulgently, “But I do! I do. I think everybody has their own private religion. I guess what bothers me is when millions have the same one. It just can’t be true. It’s just…” she screws her face up incredulously, “…what?”

Part 4: Business

One of the things you realise pretty quickly around Björk is that for all her colourful flamboyance, her eccentricity and her sometimes child-like awe and wonder, she is not naïve. She is fiercely intelligent and hard-working and despite spending the better part of her life trapped inside the distorted mirror ball of her own celebrity, her engagement with the world around her is honest and clear-sighted. In particular, the passion for nature which she espouses so readily on Biophilia would be easy to dismiss as abstract whimsy if it were not for the fact that she has proved herself unafraid to engage wholeheartedly with grassroots environmental activism and to take on big business without ever displaying a pop star’s sense of entitlement.

She described her radicalisation in a 2008 op-ed for The Times, in which she wrote about how she’d been forced to stop living “happily in the land of music-making” when she realised that “politicians seem bent on ruining Iceland’s natural environment”.

As activist groups like Saving Iceland have identified, Iceland’s bankrupt government is currently scrambling to cash in their few remaining chips by granting permission for huge tracts of land to be torn up for aluminium plants while simultaneously signing a secretive and ludicrous contract to sell off Icelandic energy producer HS Orka to Canada’s Magma Energy Corp in a deal which grants the corporation exclusive access to some of the country’s largest geothermal reserves for the next 130 years.

Björk first got involved in the protests in 2004, when she played at the Hætta concert in Reykjavík which had been organised in opposition to a new Alcoa aluminium smelter. She then founded an organisation called Náttúra and has taken up campaigning in a way that was new to her: “It was another thing I thought I’d never get into, funnily enough,” she laughs. “I’m breaking all my own taboos!”

Although Náttúra faces a huge struggle to protect Iceland’s landscape, there are echoes of similar battles being fought across the world. We talk about the Dongria Kondh tribe in Orissa, India, where I used to live, who recently won a historic battle against Vedanta Resources to save their forest lands and stop their sacred Niyamgiri mountain being turned into an open-pit bauxite mine. “It’s great,” she says, “I’ve been following this since about a year ago.”

She says she never intended to become involved in this sort of activism: “I always felt music was better if it wasn’t political, but I live on an island which I guess is about the same size as England – without Wales and Scotland – but it’s only got 350,000 people. It’s the biggest untouched area in Europe. You can imagine how we felt: not just me, but the majority of Icelanders, when we found out that behind the scenes for 20 years the right-wing rednecks had been planning to harness all of its energy. I mean, already we’re over the pollution mark that the Kyoto agreement set, so that would just be gone! I just had to do something about it.”

She says that at first she had been complacent: “We had two huge aluminium smelters and they were going to build a third one. I thought ‘that’s not going to happen’. There was a lot of protest, everybody went bonkers, people came from all over the world… and it still got built!”

After that, she could no longer content herself with just turning up for benefit concerts: “That was 2005-6, and after that I was just like…” She mimes rolling up her sleeves. “It’s about my children or my grandchildren. I had believed it would be stopped. There were a lot of people in government who were against it, but it still didn’t get stopped. I wouldn’t be able to live with myself, when I’m old and looking at my grandchildren, unless I at least gave it a whack.”

With the lack of alternative employment opportunities being cited as the critical factor, Björk decided to get creative: “In the autumn of 2008 I spent four months on it full time. It sounds maybe odd, but it seemed to me and my friends that the best way to do it was to go to the rural areas and ask ‘Why aren’t you thinking of starting other companies?’ We figured out very quickly that legally it was impossible for these people to start start-up companies. If you had a village of 500 or 1,000 people, and 20 people are unemployed, then if they could start three little companies they’d be fine. Basically they wanted to build an aluminium smelter there and then the people who were unemployed from ten villages would all come and get jobs. But if instead you could start one company that would grow their own vegetables… I mean, it doesn’t all have to be hippy, green things… you could start a data centre or an online company!”

“We basically went and wrote out lists of 500 companies that were possible to inspire people and so we basically ended up with 150 people who were cherry-picked, and we had a brain-storming weekend, and then we had a lot of really influential people in Iceland but also a lot of people who started start-up companies which nobody thought would work: like gaming companies that hire now 2,000 people but were set up by two guys who are half my age. So these kind of people. We wrote a manifesto, not a thick one but just a functional manifesto and took it to the Prime Minister and said ‘These are laws that you can change now and they’d make things easier for little start-up companies.’ It was silly things. For example, fish is under a monopoly, so you can’t have fish markets in the villages. Which is insane when they’re catching these fish right there. You can’t have sushi restaurants. It was a collection of stuff like this, you know? So that did something, not much, and then was the privatisation of access to Iceland’s energy sources. After the bank crash, it was sneaked through, so then started a year-long fight to try to raise awareness. We did a petition online, I don’t know if you saw it?”

I tell her I did see the petition, which called for a referendum to decide whether the country’s natural resources should be publicly owned. Then I tell her I also saw the remarkable series of open letters that went back and forth between her and Magma Energy CEO Ross Beaty last year, in which he at one point offered to sell her a 25% stake in the Icelandic energy company HS Orka. She eloquently rebuffed him, writing back: “you totally miss my point. i feel this company should not be privatized , it should be given back to the people. therefore i am not interested in shares.”

When I mention the letters she laughs loudly and scowls in pantomime disapproval.

“He is so cocky! So cocky! So anyway, to cut a long story short we got 47,000 people to sign a petition to give to the government to not privatise access to our energy resources. That’s like 25% of voters! But like what you were saying about India, it’s a cobweb. For three years, half of my time went into this and then in January I realised that if I didn’t go full time on my project it would never, never happen. So in January 2011 I organised the karaoke marathon and then I took the next plane out and said; ‘Now I have to focus on my project.’ I think with my project I can be proactive, do you know what I mean?”

After hosting a three-day karaoke marathon in January this year to attract attention to her calls for a referendum, Björk decided that making her own music was the best way to get people talking and engage them with environmental issues.

“That was actually one of the driving points, emotionally, for Biophilia. Instead of standing on a chair and criticising and going ‘Ner-ner-ner-ner-ner’ why didn’t I come up with solutions? I ended up being… touch-screens… internet… ok… solutions. After the bank crash and seeing all the people who lost their houses and lost their pensions because of what 20 crazy venture-capitalists did, my problems were superficial. After trying to encourage people who’ve got nothing, to tell them: ‘Come on!’” She claps emphatically. “‘You could start your own fishing company! You could grow mussels! Harness the tide! You can do it!’ Then when you come back to your home, to your studio… you cannot be lazy. It’s like karma. If you’re saying to other people that it’s no big deal, then you have to give it a go yourself. You have to practise what you preach, you know?”

It wasn’t just witnessing other people in trouble that spurred her on, she had her own problems as well: “There are so many things that used to work that don’t work anymore. Not only with the music industry, but I lost my voice… I got nodules on my voice and had to learn a totally new technique. I didn’t know if I could sing again. So on so many different levels it seemed like all the old systems were off the table, and it was a case of: ‘Let’s just do simple stuff that works’. It’s an interesting irony that this project maybe comes across as being pretentious and complicated, but for me, how I experienced it for three years was very DIY. We’d run out of budget. It was as if all these old systems, these palaces, had tumbled down and it’s like: ‘Ok. Here’s a spoon. Here’s a cup.’” She picks them up off the table and mimes a pestle and mortar: a picture of single-minded determination.

You felt like you could rip it up and start again?

“Yeah. That’s how it felt to me to do it really.”

Having spoken about the failings of the music industry in general, and about running out of budget herself, I’m intrigued as to how she manages to fund a project as singular and ambitious as Biophilia. The live show alone is reported to be a vastly expensive undertaking. Is she actually making any money?

“Well I’ve always felt that because I’ve got money from my albums that I should use them to make the next project. It’s been one of the reasons that every project has been so different, because I felt that somebody was rewarding me for being brave! If I stopped being brave it would stop! If I started being stingy, the project would be stingy. So far in my career, I’ve usually used the money from each project to pay for the next one. So for this project, I could pay for the making of the album, that is the music. I got the Polar Music Prize, from Sweden, a year ago, and that’s quite a generous prize, so I paid for the instruments with that, but I couldn’t pay for the apps.”

The Polar Music Prize is worth one million Swedish kronor, just under £100,000, which paid for the unique instruments she showcased at her summer residency at the Manchester International Festival.

“The concert in Manchester, we just about made it on zero. I mean, that’s success, as far as I’m concerned. I’ve got a house in England, I’ve got a house in New York, I’ve got a house in Iceland, I don’t need anything more, you know? I’m fine. Once I stop making music… once I stop making money from music, I’ll sell one house! So after I stop making money from music… I can make albums for a few years, at least the next ten years, from selling the houses I’ve got! I’m not trying to be rich; it’s more that I want to solve riddles. For example, with the music industry: it tumbled ten years ago, and I felt that I wasn’t doing anything about it, really. Probably I was having it too good or something! But now I can say ‘I postponed it too long’. Also maybe because I come from this punk background where there was only 80,000 people in the village I was brought up in – the capital, you know? – and there was a big company there already that sold Abba and Beethoven or whatever, put out the commercial Icelandic musicians. We didn’t want to be part of that. We knew that it’s no big deal putting out an album. I think a lot of musicians think it’s this kinda thing where you have to send your music to all the big labels. It’s more of a psychological, confidence thing: ‘If I’m good enough, they will like my demo.’ But I mean I did it all for ten years. I’ve done it: making the album in somebody’s bedroom, making the poster yourself.”

Do you think that’s what you’d be doing if you were just starting out now?

“I think so. I think because I had that background, I knew when the music industry started tumbling that it wasn’t a big deal. I knew it from experience. I haven’t always been able to just hand out my demo and get a response. I’ve done it myself. Taking buses around Reykjavik and putting the posters up myself. Now, with the internet, that’s exactly what you do. What I’m trying to say… in a really complicated way, I’m sorry!… is that I felt that if somebody would know what could be possible it would be somebody of my generation. I’ve had it quite good for a decade, so that I can take this kind of risk, you know? But I think it was also very driven by the stuff I was doing in Iceland.”

Part 5: Boundlessness

Björk was never going to be happy with an ordinary, workaday world tour for Biophilia. Instead, she plans to spend the next three years visiting just eight international cities for a series of six-week residencies. She will spend around a month and a half in each location, and her venues will be carefully chosen with science museums more likely to be selected than arenas. She plans to perform twice a week to relatively intimate audiences of fewer than 2,000 people, while the rest of the time the venues will host a series of music-education workshops in collaboration with local schools. At long last, her dream of becoming a music teacher will become a reality, albeit in a fittingly fantastical way.

A conventional tour is unthinkable in part because of how absurdly unwieldy her instruments are. While the high-tech touch screens that her band played on the Volta tour have directly influenced her composition of Biophilia, the machines she will use to play it are the sort of objects which will strike fear into the hearts of roadies everywhere. There is the vast barrel harp known as the Sharpsichord and then there are a further four 10-foot pendulum-harps whose strings are plucked by gravity’s pull. There is a pipe organ controlled by midi files and a celeste which has been re-fitted with bronze gamelan bars to create a hybrid called a Gamaleste. In order to play the bassline on ‘Thunderbolt’ she will have a twin Tesla coil system suspended over the stage. You know, because a single Tesla coil is just never enough, is it?

While she’s already told me how important Iceland is to her, it’s clear Björk relishes the opportunity to travel. Likewise her music has incorporated influences and collaborators from the far reaches of the globe, from Inuit throat singer Tagaq to Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté, and she recently released a series of Biophilia remixes by Syrian maverick Omar Souleyman. As I’ve traveled and worked in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I’m particularly interested in how she managed to stumble across Congolese dance pioneers Konono Nº1 before inviting them to play on Volta?

“I can’t remember… I guess somebody sent me a link to them – I guess that’s how you find out about new music these days!”

Does she spend a lot of time on the internet? The subject matter of Biophiliasuggests she has the sort of mind that could spend weeks falling down Wikipedia’s rabbit holes.

She laughs: “Yeah! Yeah, I do a little bit! I still haven’t gotten into Twitter and Facebook and all that. I’m trying, with this project, because it has that educational streak so I feel I want to talk about it. In a way it’s not about me. It’s the frustrated music teacher in me that’s gagging to find a platform! I mean obviously I do emails and use it to find music, but I also go to CD shops, so it’s a bit of both.”

Going back to Konono Nº1, she adds:

“I wanted to go to Congo, when I worked with them, but it was exactly when… when was it, it must have been 2005? It was like the week before that this big war had kicked off, and I asked the people who put Konono Nº1 out, who are Belgian, and they said that even they couldn’t go there at the time. So I couldn’t go, although of course I wanted to. I ended up going to Mali and working with Toumani Diabaté. In the end I met Konono Nº1 in Belgium. They were fun! We had a language barrier, but it was all translated. I would have liked to have worked more with them but their schedule and mine was tricky. My original dream was to persuade Timbaland to come with me to Congo. Not just for a short week or something but for a few months, and somehow combine his beats… because he’d been asking me for ten years to work together and I never understood exactly how I was going to enter that world. But I think between me and Timbaland, I would have been the anthropologist! That would have been my role.”

Björk is well cast as a pith-helmeted musical anthropologist, and having recorded in the past with not just the aforementioned musicians but also the likes of Thom Yorke, Antony Hegarty, Mike Patton and Rahzel I ask whether she’s seeking out future collaborations?

“Yeah, for sure,” she replies, “I’m not that greedy though, because to be honest I’ve been doing them for so long that I understand that it’s not just about ‘shopping’, you know? In the end of the day, if you have good chemistry then you have good chemistry. The chemistry is kinda more important than the two individuals. Usually, if you’re lucky, at any given point you might have chemistry with maybe one or two musicians. For example, I became good friends with Antony before we even sang together. It takes a while. I don’t know if you heard what I did with Dirty Projectors? That was one of the most exciting things I’ve done recently.”

As she said earlier, the songs are the core for her. I wonder whether she sees a triumph of style over content in the contemporary pop charts. Is Björk interested in or by Lady Gaga?

Her reply is cautious: “I definitely like some of the outfits she’s worn. I definitely admire her for her courage – it was getting really boring! It was like everybody was just really conservative, and nobody was taking any risks. I love theatrical stuff. I think all of us have a theatrical side and a not-so-theatrical side. The music? It’s not my thing. I mean, I don’t judge it. One thing good about music is that you can have all sorts of music. You can have… easy-listening new age music…which actually is even bigger than Gaga! Classical music. You can have billions…”

There’s room for everything.

“There is room for everything. Something that is quite common though, and I’ve noticed it even though things have changed a lot, is that there always seems to be room for a lot of male singers, and they don’t get asked to duel. You have Jay-Z and Kanye West being best mates. There’s always room for many male characters.”

Whereas women tend to be pitted against one another?

“Yeah, still it’s like ‘Christina vs. Britney’. Why? I don’t want to be put in a position where I have to attack her. I thought it was really weird and unfair when M.I.A. and Joanna Newsom were asked about Gaga and then because they didn’t like her music, it was immediately big news online and they had to shoot each other down. It’s like the three new, most happening female pop girls, the same kind of age, and they had to shoot each other down! Guys are never asked to do that. It’s just ‘the more, the merrier’, you know?”

I ask her whether she thinks of herself as a feminist and she draws a deep breath:

“In the same way as religion… I am very spiritual, but I don’t belong to any… ‘party’. The same with feminism. I get really scared and worried and run the other way the minute it becomes a dogma, or a doctrine. My mum’s generation, the hippies, were quite radical when it came to those things and I felt that for my generation the best thing we could do for women was just to go and get things done instead of pointing your finger forever. I think it’s better for me to focus my energy on just getting things done. Especially as you get older, because there seems to be this kind of invisible line that you’re just supposed to go home and stop doing things, which is odd. My idols have often been authors, because we have so many in Iceland.”

Who do you idolise?

“So many! In Iceland we are the nation that writes most books, reads most books and buys most books per person in the world. Our heroes are always authors and they always did their best work between 50 and 60. You’d do your angry, hardcore, ‘pose-y’ poetry book when you’re 21, when you’re an arrogant youth and you beat people up and all this kind of stuff! People will say: ‘Let’s see… when she’s 40 or 50, then she’ll do her mature work…’”

Björk, despite not appearing to abide by what she would call the ‘grid-like’ nature of aging, is now 45. The eclectic, ecstatic music she has made her life has at times been angry, hardcore and even ‘pose-y’. Is Biophilia her mature work?

“I don’t know! I definitely feel like I personally broke through some old, stagnated habits on this project which might enable me, for the next ten years or so, to do better music.”

For a moment she is lost in thought, rotating her jaw. She is still as driven as she always has been, still as exacting in the demands she places on herself as she scampers ceaselessly into uncharted territory: pop music’s most fearless explorer. She smiles ruminatively:

“I still feel I’m just as far away from what I want to do… but, you know? That’s just the way it is, right?”

“I don’t feel like there’s much to be gained by admitting that you’re part of the wallpaper in a capitalist system that you help propagate.” Stephen Malkmus is lying on a sofa in the book-lined lobby of a self-consciously upmarket hotel in Soho. The erstwhile Pavement ringleader is talking about class, about the role of musicians and music fans and about the futility of rebellion, but he’s doing it with characteristic nonchalance. He never quite seems to be taking himself entirely seriously, and as he reclines I realise I’m being offered an irresistible visual metaphor: Stephen Malkmus is so laidback he’s horizontal.

“I don’t feel like there’s much to be gained by admitting that you’re part of the wallpaper in a capitalist system that you help propagate.” Stephen Malkmus is lying on a sofa in the book-lined lobby of a self-consciously upmarket hotel in Soho. The erstwhile Pavement ringleader is talking about class, about the role of musicians and music fans and about the futility of rebellion, but he’s doing it with characteristic nonchalance. He never quite seems to be taking himself entirely seriously, and as he reclines I realise I’m being offered an irresistible visual metaphor: Stephen Malkmus is so laidback he’s horizontal.

The men sat in the front row of EasyJet flight 5443 from Gatwick to Budapest were wearing sunglasses and sheepish expressions. A fellow passenger caught their eye. “Are you guys in a band?” she smiled. “Yeah,” sighed Maxim Reality as he glanced across at Liam Howlett and Keith Flint, a man who doesn’t find it easy to look inconspicuous. “We’re The Prodigy.”

The men sat in the front row of EasyJet flight 5443 from Gatwick to Budapest were wearing sunglasses and sheepish expressions. A fellow passenger caught their eye. “Are you guys in a band?” she smiled. “Yeah,” sighed Maxim Reality as he glanced across at Liam Howlett and Keith Flint, a man who doesn’t find it easy to look inconspicuous. “We’re The Prodigy.”

It is early May 2011, and twenty musicians find themselves together for the first time in a recording studio somewhere in Brussels. Producer, bass-player and musical ringleader Vincent Kenis is marshalling his troops: half of them represent ‘Congotronics’ – drawn from the ranks of Konono N°1 and Kasai Allstars – the other half are ‘Rockers’, flown in from the States, Sweden, Argentina and Japan. The atmosphere, according to Matt Mehlan of Skeletons, is “intense”.

It is early May 2011, and twenty musicians find themselves together for the first time in a recording studio somewhere in Brussels. Producer, bass-player and musical ringleader Vincent Kenis is marshalling his troops: half of them represent ‘Congotronics’ – drawn from the ranks of Konono N°1 and Kasai Allstars – the other half are ‘Rockers’, flown in from the States, Sweden, Argentina and Japan. The atmosphere, according to Matt Mehlan of Skeletons, is “intense”.

Anyone who has spent time in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, will know that it’s a city that bustles with an industrious and infectious energy. Maybe it was living there that inspired Mawangu Mingiedi to take that energy and apply it like jump leads to the Bazombo trance music he had grown up with near the Angolan border. In doing so, he created a band called Konono No.1 and revolutionised a musical tradition that stretched back hundreds of years.

Anyone who has spent time in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, will know that it’s a city that bustles with an industrious and infectious energy. Maybe it was living there that inspired Mawangu Mingiedi to take that energy and apply it like jump leads to the Bazombo trance music he had grown up with near the Angolan border. In doing so, he created a band called Konono No.1 and revolutionised a musical tradition that stretched back hundreds of years.

When Charlotte Gainsbourg was 12 she made her musical debut dueting with her father, Serge, on a still notorious single called ‘Lemon Incest’. As an actress, she appeared last year as the unrelentingly sexually violent lead in Lars von Trier’s ‘Antichrist’. Hers is a career that has always playfully shrugged off social mores with an air of measured provocation, but then what else would you expect from someone whose parents breathed ‘Je t’aime… moi non plus’ to each other?

When Charlotte Gainsbourg was 12 she made her musical debut dueting with her father, Serge, on a still notorious single called ‘Lemon Incest’. As an actress, she appeared last year as the unrelentingly sexually violent lead in Lars von Trier’s ‘Antichrist’. Hers is a career that has always playfully shrugged off social mores with an air of measured provocation, but then what else would you expect from someone whose parents breathed ‘Je t’aime… moi non plus’ to each other?

Guess who just got back today? Those wild-eyed Libertines that had been away. But what brings them back? Money? Ego? Music? Love?

Guess who just got back today? Those wild-eyed Libertines that had been away. But what brings them back? Money? Ego? Music? Love?

Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is a vast, sprawling city in a vast, sprawling country ten times the size of the UK. The Congolese like to refer to their home as the “richest country on Earth”, a reference to the lush rainforest and its wealth of natural resources. Sadly, those killjoys at the International Monetary Fund like to refer to it as the “118th richest country on Earth”, coming in just behind financial powerhouses Armenia and Afghanistan, and presumably a reference to the years of conflict and political instability that have gutted the national infrastructure and left many of those resources in the hands of a motley assortment of warlords.

Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is a vast, sprawling city in a vast, sprawling country ten times the size of the UK. The Congolese like to refer to their home as the “richest country on Earth”, a reference to the lush rainforest and its wealth of natural resources. Sadly, those killjoys at the International Monetary Fund like to refer to it as the “118th richest country on Earth”, coming in just behind financial powerhouses Armenia and Afghanistan, and presumably a reference to the years of conflict and political instability that have gutted the national infrastructure and left many of those resources in the hands of a motley assortment of warlords.

Tom Waits stands in a bright spotlight in a tent dubbed ‘The Ratcellar’. He stomps out a beat, sending clouds of dust into the air, and for a sprawling twenty-eight song set he invites us into his universe.

Tom Waits stands in a bright spotlight in a tent dubbed ‘The Ratcellar’. He stomps out a beat, sending clouds of dust into the air, and for a sprawling twenty-eight song set he invites us into his universe.

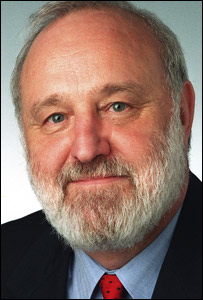

Frank Dobson has become one of the Labour Party’s defining MPs. A constructive critic of the New Labour experiment, he is a former Secretary of State for Health as well as an LSE graduate. He says he studied Economics, “In theory anyway. I know enough Economics to know when someone else is talking bollocks and that’s about it really.”

Frank Dobson has become one of the Labour Party’s defining MPs. A constructive critic of the New Labour experiment, he is a former Secretary of State for Health as well as an LSE graduate. He says he studied Economics, “In theory anyway. I know enough Economics to know when someone else is talking bollocks and that’s about it really.”