So there’s this tree in the yard behind Mac DeMarco’s house in Los Angeles. It feels good sitting in the shade beneath it, whiling away an afternoon listening to records, looking up at the light coming through the pale green leaves and smelling the faint scent of citrus. It’s a pomelo tree, Mac says. I’m not exactly sure what a pomelo is, but judging by the lumpy yellow fruit hanging from the branches I’d guess that a pomelo is a sort of shitty grapefruit.

So there’s this tree in the yard behind Mac DeMarco’s house in Los Angeles. It feels good sitting in the shade beneath it, whiling away an afternoon listening to records, looking up at the light coming through the pale green leaves and smelling the faint scent of citrus. It’s a pomelo tree, Mac says. I’m not exactly sure what a pomelo is, but judging by the lumpy yellow fruit hanging from the branches I’d guess that a pomelo is a sort of shitty grapefruit.

Across from the shitty grapefruit tree is a swimming pool, impossibly blue in the bright sun on this cloudless Californian afternoon. Moving gently across the surface in the breeze is an inflatable killer whale, floating belly up.

Next to the pool is Mac’s studio, a separate building behind his house. Inside is piled high with all manner of instruments and vintage recording gear. Next to the door there’s a pennant with a picture of a moose on it and the words ‘EDMONTON ALTA’, a memento from the Canadian city where Mac grew up and first started making music. A lot has changed since then. A lot hasn’t. Even though he now has this space, the studio still feels like a bedroom.

There’s a dark green flag with a white peace sign on it hung behind the desk, and there are various bits of Simpsons merchandise scattered around as decoration. In a rack near the door sits the copy of Playboy with Marge on the cover. On the desk there are two empty bottles of champagne, two empty beer cans, three empty water cans and three empty packs of Marlboro Reds. There are more empty cans and cigarette packs on a low table in front of a sofa on the other side of the room, detritus from last night’s impromptu recording session with a few friends. When he first cracks the door open, Mac apologises that the place “smells like a body”. He is not wrong.

Back outside underneath the tree is a glass table covered in blossom and an ashtray filled with a miniature Everest of cigarette butts. Mac is sat there now, his back to the tree, drinking coffee and talking about the life he and his girlfriend Kiera have made for themselves since moving here from New York. He says they rarely leave the property. Kiera makes bread and is learning to teach pilates. Mac makes his music. Together they look after the cat, Pickles, who has been here longer than they have.

“I think he was born under the house and has lived in this backyard his entire life,” says Mac. “We started putting food out for him about a year ago. He would come up, eat, see us and fuck off. Then later we could sit with him while he ate. Then maybe we could give him a little touch. Then we moved the food bowl in and he would eat inside. Now, that puss is sleeping in the fucking bed with us every night.” He smiles his gap-toothed smile. “Good kitty.”

Mac seems content to take things slow these days, coaxing a measure of happiness into his life like that feral cat. His new album, ‘Here Comes The Cowboy’, came the same way: slowly at first. Mac himself calls it “kind of a weird one.” There are simple little songs with just one or two repeated lyrics, there are Sly Stone-sounding funk jams and there are straight-up declarations of love for Kiera. There aren’t too many radio-friendly feel good hits of the summer. “It’s like: festival record? No no no,” shrugs Mac. “It’s slower and softer.”

In part this is a reflection of his life, which now seems a far cry from the wild and crazy stories that swirled around McBriare Samuel Lanyon DeMarco when the world first started paying attention to his antics. There was one tale from the early days, about sticking a pair of drumsticks up his ass midway through a drunken show while U2’s ‘Beautiful Day’ hit a crescendo, that followed him around for years, proving the old adage true: write as many songs and play as many shows as you want, but stick just one pair of drumsticks up your ass and they’ll never let you forget it. Still, times change.

“I’m living a pretty domesticated existence,” says Mac, gesturing around. “We have a house, I’ve been with my girlfriend for a long time… it’s not like we have a routine or anything but things are comfortable. It feels like settling down. I have way too much gear now to be able to move to another city at the drop of a pin. I think my head is just in a different space than it’s ever been in, because I’ve travelled all over the world, met all kinds of different people and had different experiences and now I’m navigating that and figuring out: ‘Where do I belong?’ ‘What is this shit?’”

Those are the sort of questions that define the human experience. We’re all trying to figure that shit out every day, making things up as we go along and desperately laying tracks in front of the train even though we’re shovelling coal into the engine at the same time. What’s different about Mac is that he’s had to do a lot of that figuring out in public.

When he first arrived in London to play his first ever UK show at Birthdays in Stoke Newington in December 2012 he was 22-years-old and had just finished touring the USA by car, doing all the driving himself. Hardly anyone had come to see him. “Chicago was fine and LA was fine,” he remembers now, “But for the most part we were playing to no-one in the middle of nowhere.”

Though he didn’t know it then, everything was about to change. The Birthdays show was sold out, and then so was the whole tour. “We were like: ‘What happened?’” he remembers. “I think it was that ‘2’ came out and people gave it good reviews, but I found it really bizarre to see the power of that. It was like: here’s the record, here’s the hype, then here’s the people. I couldn’t believe it was so immediate.”

Foreshadowing the years of hard-partying touring that was to come, when I first met Mac in Montreal just before that first London show he told me that he’d heard good things about playing in Europe: “People have been telling me that a lot of times they’ll give you a whole bunch of beer in the green room and you can take it afterwards,” he said, sounding as if he was describing a vision of paradise he’d seen in a fever dream. “That sounds good to me!”

Mac lets out a long, knowing laugh when I remind him of this. “You know, it’s funny. First tours in the United States, maybe you get one free drink at the bar,” he explains. “The promoter is like: ‘Get the fuck out when you’re done.’ In Europe they really treat you nice. They give you beer and then they’re like: ‘We made you a lasagna.’ Oh my God! You’re kidding me? That first European tour it was like a homemade lasagna every night.”

Mac blew up fast. In just under two years he went from playing that first show at Birthdays to 250 people to Kentish Town Forum to 2,300 people. He quickly built a reputation for having the best live show in town, with a wild edge and an unpredictable comic streak. I remember he closed that Forum show by playing the theme from Top Gun over and over again for something like 20 minutes. It was one of those perfect jokes that starts off funny, then isn’t funny at all, then gets increasingly hilarious the longer it goes on.

By that point, Mac was more than just a cult artist – but he did have a cult following. The Cult of Mac. “That was a trip,” he remembers. “I used to have a lot of kids wearing the exact same kit as me for a little while. Maybe there still are, but I’m not out there so much anymore. That was wild, but people go through phases. I think I’m already in the phase where it’s like: ‘Oh, he’s so played out. He’s not cool anymore’. That’s inherent, but it’s funny to watch. It’s fine with me.”

As the years have gone by and the venues he plays have continued to increase in size, Mac has responded not by becoming more outrageous but by mellowing out. It’s as if, to paraphrase Homer Simpson, he’s learned to enjoy not just the glorious highs and the terrifying lows but also the creamy middles. “It’s not like I’m pushing back on purpose,” says Mac, “but even when the shows get bigger, or maybe it’s as I get older, I feel like: ‘There’s a giant stage? A giant crowd? Then let’s play really slow and really quiet. For me musically right now that’s something different. We never did that, so it’s something new for me.”

Which brings us back to that “slower and softer” new album ‘Here Comes The Cowboy’, which – for the record – is not about cowboys at all. “I just use ‘cowboy’ as slang with friends,” Mac sort-of clarifies. “Like when you say: ‘Hey cowboy!’, but where I grew up cowboys were a thing. There was the [Calgary] Stampede, and people did cowboy activities, and there were themed-bars. For the most part, those zones were geared towards people that I didn’t really want to interface with. Jocks who wanted to call me a profanity and kick my ass. So for a long time it had a very negative connotation for me.”

Mac enjoys toying with and then confounding expectations, so it should be no surprise that the titular cowboy really signifies nothing. “For me, it’s funny and interesting to call something a cowboy record because immediately people jump to connotations,” he says. “There are a lot of things that come with that word, but the record is not a country record. It’s not really a cowboy record at all. I don’t know where that song ‘Here Comes The Cowboy’ comes from but I like it because I don’t know how it makes me feel. Is it funny? Is it strange and jarring? Maybe it’s both, somewhere in the middle. Who is this cowboy? Where the fuck is he coming from? What is he doing? I love that!”

That same instinct to confound lies behind the strange lizard-faced version of Mac who appears in the video for first single ‘Nobody’. If you’re not sure how that unsettling prosthetic mask he wears makes you feel then that’s exactly the point. “You ask yourself: ‘What is this?’, and that’s the kind of thing that interests me,” he says. “I’m just trying to create…” he puts on a mocking voice “…the content that I’d like to engage with.”

One through line in Mac’s musical life has been his insistence on recording everything himself while playing almost all the instruments, like a chain-smoking slacker one-man-band, but without the accordion he plays with his foot. He’s always done things that way. “It was a good trick for a while,” he says. “People are like: ‘You played all the instruments?’ And you’re like: ‘Well, none of them are played that well, but yes.’”

Now it’s more than just a trick or an aesthetic choice. He’s come too far to change. For this record he had touring keyboardist Alec Meen lay down some music, but something was never quite the same. “It only felt right if I played it with no metronome, just the way that it works for my hands to play it,” says Mac. “He played it perfectly and straight a million times, and I’d be like: ‘But that’s not how the song sounds’. I have a problem with needing things to be perfectly shitty.”

One of the best tracks on the new record is called ‘Finally Alone’. As the title suggests, it’s a song about seeking solitude even when you’re not sure that’s what you want. “It’s kind of a cute-sounding song, so when Alec looked at the project title he was like: ‘This song is called ‘Finally Alone’? What the fuck?’ I’ve always loved that juxtaposition of cute-sounding music and then lyrics about isolation. It’s inner turmoil. I think the theme of this record goes through that a lot. It’s about not knowing what you want and vibing on it.”

Mac’s own love of isolating himself here in his house and studio – he says he sends “almost zero” percent of his life online – got him into internet faux-outrage trouble the day the record was announced. A brief Twitter cloudburst spat drizzle at the suggestion his album ‘Here Comes The Cowboy’, with lead single ‘Nobody’, was a slight against Mitski’s similarly-titled album ‘Be The Cowboy’, with lead single ‘Nobody’. This came as a “huge surprise” to Mac, because he’d never heard of it. “Truthfully told, I’m very, very bad at keeping up with contemporary music,” he says. “I listen to music from Final Fantasy video games and The Beatles. That’s about it.”

Mac’s self-imposed period of solitude will soon be coming to an end when he returns to his first passion, playing live shows. “I still love to do it,” he says. “I think the last couple of tours of this year I was pretty burnt. Things inherently get stale after a while, but we find ways to spice it up or do something incredibly stupid onstage for an hour. It’ll be exciting to have new music.”

One of those shows will be headlining his very own mini-festival in June at Dreamland in Margate, which has a capacity of 15,000. A real long way from Birthdays. He’ll be joined by a hand-picked line-up that also includes Aldous Harding, Yellow Days, Tirzah, Thurston Moore, Amyl and The Sniffers, Girl Ray, Kirin J Callinan, and Blueprint Blue. “It should be cool!,” he says. “We have a lot of homies who are going to play.” He puts on a voice that sounds like Springsteen when he’s covering Suicide: “Dreamland, baby. It’ll be chill. It’ll be tight. Let’s rock’n’roll.”

Our time under the shady tree is interrupted because it’s time for Mac to go and have his photo taken. Mac’s first NME cover. He drives us to the location, a dreamy rural cabin that somehow exists within Los Angeles. The owner issues him with a stainless steel bucket to use as an ashtray, and Mac faithfully carries it from location to location. When he’s done we go downtown because there’s this great ramen place he’s just remembered about, and then we buy some beers and head back to the yard.

When we arrive, Andy White, who plays guitar in Mac’s band, is already there. He’s from Florida but is staying with Mac while they rehearse for the next tour. A brief aside about Andy White: He’s one of the most beautiful men I’ve ever met, with long blonde hair in pigtails and the sort of moustache that hasn’t been fashionable since 1979. Every time I’ve met him he’s been incredibly nice, he’s currently preparing to run the LA Marathon, and when I ask him where he’s been all day he tells me he’s been at the library reading about economic history. I don’t understand Andy White even a little bit but I think I’d like to be him when I grow up.

When the sun goes down we go to see Mac’s friend Eyedress play a show at a once-hip Silver Lake club called Tenants of the Trees. Eyedress is amazing – weird and wild and punk – but the crowd is kinda douchey so when the show is over Mac invites us all back to the yard. Somebody builds a fire. Mac orders an ungodly amount of pizza. The studio is opened and the fruit of last night’s recording session is played loud. If this is Mac figuring shit out, it seems like he’s doing pretty well. He’s happy. It’s late now, so that’s where we leave him. The camera pulls back endlessly into the sky and we see the final shot: Mac, fire burning, surrounded by good friends (did I mention Andy White?) and far too much pizza, finding contentment under the branches of his shitty grapefruit tree.

Originally published by NME, 3 May 2019.

So there’s this tree in the yard behind Mac DeMarco’s house in Los Angeles. It feels good sitting in the shade beneath it, whiling away an afternoon listening to records, looking up at the light coming through the pale green leaves and smelling the faint scent of citrus. It’s a pomelo tree, Mac says. I’m not exactly sure what a pomelo is, but judging by the lumpy yellow fruit hanging from the branches I’d guess that a pomelo is a sort of shitty grapefruit.

So there’s this tree in the yard behind Mac DeMarco’s house in Los Angeles. It feels good sitting in the shade beneath it, whiling away an afternoon listening to records, looking up at the light coming through the pale green leaves and smelling the faint scent of citrus. It’s a pomelo tree, Mac says. I’m not exactly sure what a pomelo is, but judging by the lumpy yellow fruit hanging from the branches I’d guess that a pomelo is a sort of shitty grapefruit.

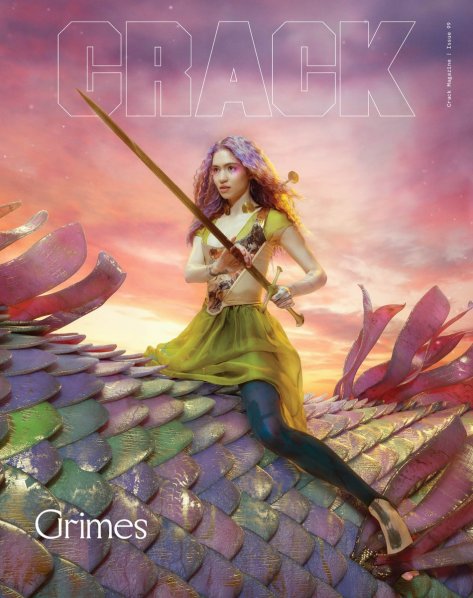

Five days before her 31st birthday, Claire Boucher is sat on a pink suede banquette in the Terrace Room of the Sunset Tower Hotel facing out towards a glistening swimming pool. Beyond it is the humdrum brilliance of another sun-bleached day in Los Angeles. If she looks like she’s just rolled out of bed it’s because she has. She’s decided to postpone her birthday celebrations until summer, but whether you acknowledge them or not, birthdays have a special way of making you reflect on the year just gone.

Five days before her 31st birthday, Claire Boucher is sat on a pink suede banquette in the Terrace Room of the Sunset Tower Hotel facing out towards a glistening swimming pool. Beyond it is the humdrum brilliance of another sun-bleached day in Los Angeles. If she looks like she’s just rolled out of bed it’s because she has. She’s decided to postpone her birthday celebrations until summer, but whether you acknowledge them or not, birthdays have a special way of making you reflect on the year just gone.

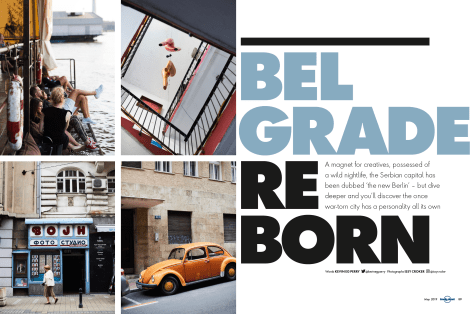

Published in Lonely Planet Traveller, May 2019.

Published in Lonely Planet Traveller, May 2019.

Published in Lonely Planet Traveller, April 2019.

Published in Lonely Planet Traveller, April 2019.

There’s a moment in the Robyn show. You know, one of those you giddily recount and discuss and dissect later in the night, looking at each other with smiling eyes; the sort you just have to post to Instagram even though your own voice is obnoxiously loud on the audio. The sort that reminds you why we bother with all this in the first place.

There’s a moment in the Robyn show. You know, one of those you giddily recount and discuss and dissect later in the night, looking at each other with smiling eyes; the sort you just have to post to Instagram even though your own voice is obnoxiously loud on the audio. The sort that reminds you why we bother with all this in the first place.

An established male rock star stumbles across a talented younger female singer. He recognises that she’s a great songwriter and tells her so, inviting her to collaborate and then tour with him. Their relationship swiftly becomes sexual. When her talent becomes apparent to others, he reacts by becoming jealous and controlling. Under the influence of drugs and alcohol, his behaviour becomes increasingly erratic and disturbing.

An established male rock star stumbles across a talented younger female singer. He recognises that she’s a great songwriter and tells her so, inviting her to collaborate and then tour with him. Their relationship swiftly becomes sexual. When her talent becomes apparent to others, he reacts by becoming jealous and controlling. Under the influence of drugs and alcohol, his behaviour becomes increasingly erratic and disturbing.

During a State of the Union in which Donald Trump at one point seemed to take personal credit for inspiring the record number of women now in Congress, most of whom ran in direct opposition to him, there was one woman whose tireless campaigning and pursuit of social justice played a pivotal role yet went unmentioned. When this speech is written up in the history books, they shouldn’t forget the name Kim Kardashian West.

During a State of the Union in which Donald Trump at one point seemed to take personal credit for inspiring the record number of women now in Congress, most of whom ran in direct opposition to him, there was one woman whose tireless campaigning and pursuit of social justice played a pivotal role yet went unmentioned. When this speech is written up in the history books, they shouldn’t forget the name Kim Kardashian West.

Lizzette Martinez was a 17-year-old high school student hanging out at the mall in Miami when she met R Kelly by chance in 1995. Despite the incongruous setting she recognised him immediately – the previous year he’d had his first No1 hit with “Bump N’ Grind” – and after the briefest of conversations, she says one of his bodyguards passed her Kelly’s phone number. Martinez was an aspiring R&B singer and hoped this could be her big break. She rang Kelly and agreed to join him for dinner.

Lizzette Martinez was a 17-year-old high school student hanging out at the mall in Miami when she met R Kelly by chance in 1995. Despite the incongruous setting she recognised him immediately – the previous year he’d had his first No1 hit with “Bump N’ Grind” – and after the briefest of conversations, she says one of his bodyguards passed her Kelly’s phone number. Martinez was an aspiring R&B singer and hoped this could be her big break. She rang Kelly and agreed to join him for dinner.

São Paulo is the largest city in the western hemisphere, a vast and sprawling concrete jungle whose metropolitan area is home to some 21 million souls and more high-rises than anywhere else on earth. Yet as you walk the crowded streets it’s easy to spot buildings that have been left empty or abandoned, often half-hidden behind sheets that flap in the breeze, the architectural equivalent of Miss Havisham’s wedding dress. The best estimate is that there are more than 200,000 vacant buildings in the city.

São Paulo is the largest city in the western hemisphere, a vast and sprawling concrete jungle whose metropolitan area is home to some 21 million souls and more high-rises than anywhere else on earth. Yet as you walk the crowded streets it’s easy to spot buildings that have been left empty or abandoned, often half-hidden behind sheets that flap in the breeze, the architectural equivalent of Miss Havisham’s wedding dress. The best estimate is that there are more than 200,000 vacant buildings in the city.

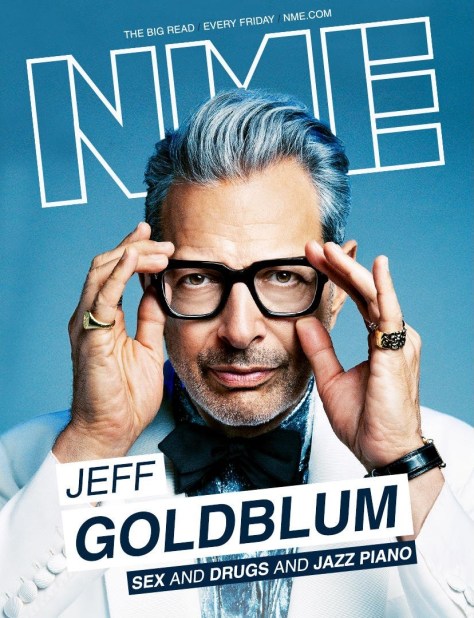

Jeff Goldblum lost his virginity the same night he made his professional stage debut. It was Tuesday July 27, 1971, and he was a gangly 18-year-old from Pittsburgh who had moved to New York the previous summer to follow his dream of becoming an actor. He was studying at the Neighborhood Playhouse under the great acting coach Sanford Meisner, and had managed to get a part in the chorus of a new musical adaptation of Two Gentlemen of Verona. Opening night at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park was a success, and afterwards some of the cast and crew ended up at dinner together.

Jeff Goldblum lost his virginity the same night he made his professional stage debut. It was Tuesday July 27, 1971, and he was a gangly 18-year-old from Pittsburgh who had moved to New York the previous summer to follow his dream of becoming an actor. He was studying at the Neighborhood Playhouse under the great acting coach Sanford Meisner, and had managed to get a part in the chorus of a new musical adaptation of Two Gentlemen of Verona. Opening night at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park was a success, and afterwards some of the cast and crew ended up at dinner together.

No matter who is behind the decks come 7am, Warung Beach Club always has the same headline act. The main room of the 2,500-capacity temple to dance music on the Brazilian coast faces east towards the south Atlantic, which means God herself does the lighting. “When the sun comes up, it’s magical,” says club founder Gustavo Conti, standing on a terrace overlooking the beach. “That’s because nature is magical, and we’re here in it.”

No matter who is behind the decks come 7am, Warung Beach Club always has the same headline act. The main room of the 2,500-capacity temple to dance music on the Brazilian coast faces east towards the south Atlantic, which means God herself does the lighting. “When the sun comes up, it’s magical,” says club founder Gustavo Conti, standing on a terrace overlooking the beach. “That’s because nature is magical, and we’re here in it.”

Why is NME writing about Mavis Staples in 2018? That’s a reasonable question, and it deserves an honest answer. We’ll get into that in a moment, but first I should say: Don’t worry, she’s not dead. Mavis Staples is alive, and despite being only a year shy of her 80th birthday she’s in such rude health that when she played the Ford Amphitheatre in Los Angeles this weekend her performance was alternately spellbinding and ass-kicking. Her voice sounded strong and pure and righteous, and she moved exuberantly around the stage and cracked jokes between songs. There is no sound on earth more joyful than Mavis Staples singing, except maybe Mavis Staples laughing.

Why is NME writing about Mavis Staples in 2018? That’s a reasonable question, and it deserves an honest answer. We’ll get into that in a moment, but first I should say: Don’t worry, she’s not dead. Mavis Staples is alive, and despite being only a year shy of her 80th birthday she’s in such rude health that when she played the Ford Amphitheatre in Los Angeles this weekend her performance was alternately spellbinding and ass-kicking. Her voice sounded strong and pure and righteous, and she moved exuberantly around the stage and cracked jokes between songs. There is no sound on earth more joyful than Mavis Staples singing, except maybe Mavis Staples laughing.

In Lenny Kravitz’s bedroom, at his grand home in the centre of Paris, there is a photograph on the wall in a gold frame. It was taken on 16 July 1971 by his father, Sy Kravitz, and shows the Jackson 5 onstage at Madison Square Garden. It was the first show little Lenny ever attended. It was a night that changed his life.

In Lenny Kravitz’s bedroom, at his grand home in the centre of Paris, there is a photograph on the wall in a gold frame. It was taken on 16 July 1971 by his father, Sy Kravitz, and shows the Jackson 5 onstage at Madison Square Garden. It was the first show little Lenny ever attended. It was a night that changed his life.

Originally published in Lonely Planet Traveller, October 2018.

Originally published in Lonely Planet Traveller, October 2018.

Let’s get right to the heart of this thing. Let’s ask somebody who was there. About 24 hours ago I was sitting in the baking LA heat listening to Mark Lanegan tell me – in that voice that sounds like gravel in a gale – about the first time he ever heard Sub Pop’s most famous signing. It was the tail end of the 80s and he was still living in Ellensburg, a small town smack in the middle of Washington state, and singing with Screaming Trees, when he got a phone call from his friend Dylan Carlson.

Let’s get right to the heart of this thing. Let’s ask somebody who was there. About 24 hours ago I was sitting in the baking LA heat listening to Mark Lanegan tell me – in that voice that sounds like gravel in a gale – about the first time he ever heard Sub Pop’s most famous signing. It was the tail end of the 80s and he was still living in Ellensburg, a small town smack in the middle of Washington state, and singing with Screaming Trees, when he got a phone call from his friend Dylan Carlson.

The first thing I notice as I step off the plane is the desert heat. On average, Phoenix has 299 days of sunshine every year, while nearby Yuma is not just the sunniest place in the United States, but actually holds the world record for average annual sunshine: an incredible 4,300 hours of sun each year.

The first thing I notice as I step off the plane is the desert heat. On average, Phoenix has 299 days of sunshine every year, while nearby Yuma is not just the sunniest place in the United States, but actually holds the world record for average annual sunshine: an incredible 4,300 hours of sun each year.

“She’s a good girl, loves her mama. Loves Jesus and America too. She’s a good girl, crazy ’bout Elvis. Loves horses and her boyfriend too. It’s a long day, livin’ in Reseda…”

“She’s a good girl, loves her mama. Loves Jesus and America too. She’s a good girl, crazy ’bout Elvis. Loves horses and her boyfriend too. It’s a long day, livin’ in Reseda…”

There’s this moment three minutes and twenty-five seconds into ‘Black Smoke Rising’, the last song on Greta Van Fleet’s double EP ‘From The Fires’, where the music has built with such unstoppable momentum that when singer Josh Kiszka roars: “YEEEAAAHHHHH” it feels as inevitable and powerful as an avalanche, or a tornado. It is rock’n’roll as elemental force. It is the sort of sound which makes this writer leap into the air to attempt an ill-advised scissor kick while his cat eyes him warily. It is very good.

There’s this moment three minutes and twenty-five seconds into ‘Black Smoke Rising’, the last song on Greta Van Fleet’s double EP ‘From The Fires’, where the music has built with such unstoppable momentum that when singer Josh Kiszka roars: “YEEEAAAHHHHH” it feels as inevitable and powerful as an avalanche, or a tornado. It is rock’n’roll as elemental force. It is the sort of sound which makes this writer leap into the air to attempt an ill-advised scissor kick while his cat eyes him warily. It is very good.

What do you mean, you’ve never seen ‘Blade Runner’?

What do you mean, you’ve never seen ‘Blade Runner’?

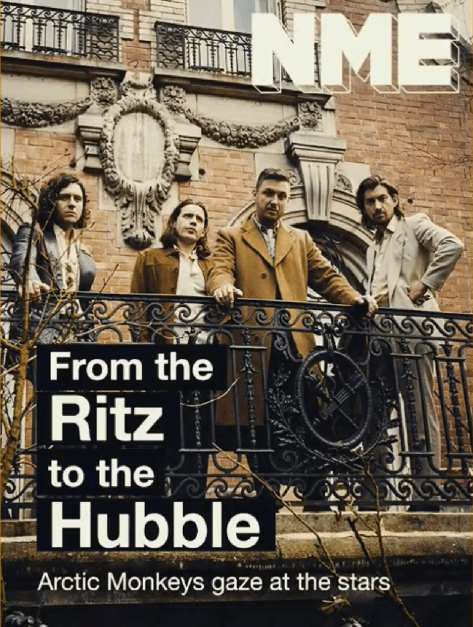

Johnny Ramone, Jayne Mansfield, Cecil B. DeMille: The stars were out last night at Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles, the silent majority joining the lairy still-living to see Alex Turner unveil his latest sashay towards songwriting immortality.

Johnny Ramone, Jayne Mansfield, Cecil B. DeMille: The stars were out last night at Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles, the silent majority joining the lairy still-living to see Alex Turner unveil his latest sashay towards songwriting immortality.