1. Phoenix and Scottsdale

Discover why Frank Lloyd Wright found inspiration in these twin cities – and see the architect’s influence writ large

At dusk, downtown Scottsdale’s Valley Ho Hotel looks like the sort of place Don Draper would come to get away from it all. As the sun sets, guests sip cocktails by the patio fire pit, reclining on loungers that mix retro and modern design as if they were drawn for The Jetsons, then magicked into reality.

Yet this is no ersatz recreation of ’50s cool – it’s the real thing. Opened in 1956, the Valley Ho was a magnet for the likes of Bing Crosby, Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh. In 1957 it hosted the wedding reception of Robert Wagner and Natalie Wood, and it’s said that Zsa Zsa Gabor and her daughter Francesca rode horses around the hotel. Presumably not while the wedding was still going on.

‘We were a resort community back then, so Hollywood stars came here, because the paparazzi wouldn’t follow them,’ explains Ace Bailey, who runs an art and architecture tour in Scottsdale. ‘They could come here for “recreation” and maintain their anonymity.’

That much hasn’t changed. ‘To this day, the hotel will not release its current guest list to anybody except hotel staff, so it’s very discreet,’ adds Bailey, before reeling off a list of contemporary Hollywood stars she’s spotted hanging around the lobby recently.

The Valley Ho is not alone. Scottsdale and Phoenix are dotted with superb examples of mid-century architecture and design, much of which displays the fingerprints of the man generally regarded as America’s greatest architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Wright came to Phoenix in 1928 to work as a consultant on the Arizona Biltmore Hotel. A decade later, he returned to build Taliesin West, his winter home, school and studio 26 miles from Phoenix. The real genius of Wright’s design is his ability to ‘bring the outside in’. In the living room, the sunlight streaming through the glass walls and translucent roof makes the garden feel like just another part of one contiguous space.

In the drafting room where Wright created perhaps his best-known work, New York’s Guggenheim Museum, a group of young architects scratches away. They are students at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture and just as in Wright’s day, they are encouraged to get their hands dirty. They have to build their own rudimentary abode in the nearby desert to ensure they truly understand the basics of designing shelter.

And the students are spoilt for inspiration. Phoenix Art Museum sprawls over 26,500 square metres, housing work from the Renaissance to today. In one hallway, adults and children alike lose themselves in their distorted reflections in the polished surface of Anish Kapoor’s sculpture Upside Down, Inside Out. Further on, they wander through American art history from an iconic portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart to modernist work by Georgia O’Keeffe.

Across town at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, visitors gaze at Knight Rise, an installation by the Californian artist James Turrell that frames the sky in a disorientating fashion. Upon leaving, they’re hit by a riot of colour from graffiti artist James Marshall, also known as Dalek.

Even public buildings, like the Scottsdale City Hall and Library, are prime examples of Southwestern architecture, influenced by the clay adobe dwellings once built by the native Hopi people. ‘It’s minimalist, without any froufrou,’ says Bailey. ‘We’ve got great neighbourhoods full of mid-century architecture, as well as structures that are true adobe compounds. It’s quite a mix.’

The blurring of past and present is still going on back at the Valley Ho, where the drinkers are determinedly stretching the cocktail hour into the night. They’ve moved indoors to sit beneath concrete block walls that show Frank Lloyd Wright’s undying influence. While they toast to the future, the music in the air is pure Rat Pack.

From central Scottsdale, follow the Arizona 101 Loop north for 35 minutes to reach the edge of the McDowell Sonoran Preserve.

2. McDowell Sonoran Preserve

Hit the dusty trail between majestic saguaro cactuses as you explore the archetypal desert of the American West

Like the wagon trains that once traversed this desert, the sun is heading west. As the light moves, the shape of the huge boulder known as Cathedral Rock seems also to warp and mutate as shadows pass across its face. In the foreground, giant saguaro cactuses stand proud and tall. Instantly familiar from their appearance in many hundreds of Westerns, they are also ancient markers. The saguaro grow an average of a foot per decade, so those towering 20 or 30 feet will have stood on that spot for around 250 years. They are the constant watchmen in the ever-changing landscape, yet adventure guide Phil Richards has a more immediate concern.

The ground is scattered with balls of jumping cholla, a cactus that looks so cuddly it has earned the nickname ‘teddy bear cactus’. Phil has just lightly placed one of these balls onto his arm to demonstrate their strength and he’s already struggling to prise it free from his flesh with a length of wood.

‘They may look soft, but if they get onto you they won’t let go,’ he explains, pointing out the strong barbs that cover the plants. They’re known as “jumping” because they latch on so hard even when brushed past that cyclists and hikers will swear they jumped out at them. Their real purpose is to hook themselves onto passing rodents and when the poor creatures try to burrow down, they’ll find themselves stuck to the cactus and inadvertently doing the job of planting it. Invariably, the animal is killed in the process. ‘This gives rise to their other name,’ says Phil darkly. ‘The “skeleton cactus”.’

For a desert, the Sonoran has a relatively lush terrain and is covered in plant life that blooms in spring. However, that doesn’t make it an easy place to survive. Phil takes issue with John Ford’s 1948 western 3 Godfathers, in which John Wayne finds himself stranded in this very desert. In need of water, he hacks the top off a barrelhead cactus and squeezes the pulp into his flask.

Sadly, this sort of thing only works in the movies. In truth, the moisture in a barrelhead is so filled with acids that it will most likely give you diarrhoea – not useful if you’re already dehydrated and stranded in a desert.

‘This is a unique desert,’ says Phil. ‘We’ve got about 3,500 varieties of plant out here, including a number of cactuses found nowhere else, and that’s because of the climate. We don’t get a hard freeze.’

The desert, ranging from Sonora in Mexico to the south of California, covers a swathe of Arizona. Here in the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, there are 30,200 acres of protected land: nothing can be built and no motorised vehicles may travel its 146 miles of trails.

‘It’s very peaceful here,’ says Phil, whose transport of choice is the mountain bike. ‘The only things you hear are your gears shifting and your wheels on the gravel.’ His quiet progress provides many opportunities to spot desert wildlife – he points out Gila monsters (venomous lizards), tusked, pig-like javelinas and grazing mule deer.

He says that it’s the beauty of the land itself, though, that keeps him coming back day after day, whether he’s guiding a group or not. ‘You can never get enough of the desert,’ he says, ‘so the best way to get more is just to ride out to a different spot.’

With that, he’s off again, dashing along a sandy trail, but still mindful enough to keep clear of the jumping cholla.

Take Interstate 17 north until you reach Flagstaff, then US-180 onwards to Grand Canyon National Park. It’s about a four-hour drive.

3. The Grand Canyon

Bear witness to the USA’s greatest landscape of all, then clamber down into it

The Grand Canyon gives no warning. Approaching from the south through the great thickets of ponderosa pine that make up the Kaibab National Forest, there is no indication of the spectacle to come. Deer dance between the trees, seemingly oblivious to their proximity to the void. Only at the precipice does the canyon reveal itself, the earth simply dropping away to reveal one of nature’s most audacious wonders. It is a mile deep and 18 miles across at its widest point. Gazing out at this great chasm of red rock shifts your perspective in a skipped heartbeat. The scale of it humbles man’s greatest constructions: stack three Empire State Buildings on top of one another and you still wouldn’t reach the rim. One lookout stop says it all: The Abyss.

It is not just the size of the canyon that startles but the sweep of history it illustrates. It is six million years since the Colorado River first found this route to the Gulf of California, and began slicing down through the soft top layers of dirt and rock. On it went, patiently cutting through sandstone and limestone before it reached its current level more than 1,500 metres below the rim. It is still getting deeper, although at a slower rate now that it has reached the hard basement rock. The river is now 730 metres above sea level and scientists believe it will keep going down, millimetre by millimetre, year after year, until it reaches the level of the sea, where all rivers stop.

To better understand the canyon, it’s necessary to leave your perch on the brink and descend into it. Hikers Katie and Nic Hawbaker, from nearby Flagstaff, have done so several times. Today, they’re climbing the Bright Angel Trail, the Grand Canyon’s most popular, which descends 1,370 metres to the Colorado River. From there, it joins the River Trail leading to Phantom Ranch in the canyon base, where they camped last night.

‘It’s totally different at the bottom,’ says Katie. ‘It’s magical. We can’t imagine how long it took to carve out the canyon or where the river was initially. It’s just so deep.’

Another way to attempt to get to grips with the sheer scale of the place is to get over it. From a Maverick Helicopters’ chopper, it’s possible to see the Painted Desert and follow the Colorado River before diving through the Dragon Corridor, the widest and deepest part of the canyon. For peak impact, though, it’s hard to beat the early moment when you’re ambling along 15 metres above the treeline of the ponderosas, then suddenly you’re 1,500 metres over the rushing waters.

It’s all a far cry from 1893, when hotelier Pete Berry first opened a crude cabin at Grandview. Berry had come to the canyon in 1890 as a prospector and staked the Last Chance copper claim 915 metres below. The ore was rich, but the vast cost of transporting it to the rim doomed the whole operation.

Before long, President Theodore Roosevelt realised the canyon needed to be protected. He made it a national monument in 1908, having declared: ‘Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is. Do nothing to mar its grandeur, sublimity and loveliness. You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is to keep it for your children, your children’s children, and all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American should see.’

Leave Grand Canyon National Park by the East Gate and continue along Arizona 64 until you reach Cameron. Then take US-89 north towards Page. Allow two hours in total.

4. Antelope Canyon & the Navajo Nation

Watch the sunlight paint pictures in Antelope Canyon, teeter on the edge of Horseshoe

Bend and get close to the land in a traditional Navajo hogan

It is a cool, still morning and Baya Diné is awake early to tend to her flock. As the curly horned Navajo-Churro sheep graze across the wide-open plains, her big white Maremma sheepdog Elvis keeps the stragglers in check. Baya knows every inch of this land as if it were a part of her, from the spectacular curve of Horseshoe Bend a few miles north to Antelope Canyon in the east.

Baya’s family has farmed here for 15 generations. Her ancestors lived in hogans, homes built with cedar and juniper logs, and packed with earth, which could be taken down and moved seasonally. Baya herself grew up in her grandmother’s hogan, a permanent wooden structure which still stands and was, improbably, built with pieces of the set left over from the making of the 1965 epic The Greatest Story Ever Told, after her grandfather appeared in the film as an extra. Baya’s grandmother, who had always lived in buildings made of earth, considered it a palace.

‘My grandmother lived here the way the Navajo had lived for many generations,’ Baya explains. ‘She herded her sheep through this land and then down the ridge all along to where the town of Page is now. This is a harsh environment and they were just trying to survive, foraging and living off the land. They were one with it, really. This was part of them and their way of life.’

Baya’s land is in the west of the Navajo Nation, which at 16 million acres is the largest Native American reservation in the US. Although her ancestors moved their homes to different spots regularly, they have left no trace beyond a few petroglyphs, arrowheads and shards of broken pottery.

‘You’d never know now where their homes were,’ says Baya. ‘These days there are buzzwords, like “sustainable” and “green-built”, but that was just a way of life for Native Americans. They reused and recycled way before it was the thing to do.’

On the land where Baya now stands, the ancient Navajo stories say there was an antelope birthing area. The animals also gave their name to the nearby Antelope Canyon, although the Navajo refer to the area as ‘Tsé Bighánílíní’, which translates as ‘the place where water runs through rocks’.

Entering the now-dry canyon on a Navajo-run tour, visitors are awed into hushed tones when they see how water has sliced a narrow crevasse through the sandstone. Inside the slot canyon there’s an otherworldly atmosphere, as the only light comes from sunbeams playing tricks upon the canyon walls as they fall 40 metres. Flash flooding is still a danger and tour guides with torches pause to point out where previous floods have lodged trees high between the canyon walls.

Photographers jostle each other for the best spots and angles – no surprise considering the world’s most expensive photograph was taken here. Landscape photographer Peter Lik sold Phantom, an image of dust in the canyon appearing to take the form of a ghost, for $6.5m in November 2014.

West of Antelope Canyon, on the other side of the small town of Page, sits Horseshoe Bend, where photographers have no such problem competing for a spot. The only danger here is getting too close to the 300-metre drop that overlooks the meandering path of the Colorado River as it travels west from Lake Powell to the start of the Grand Canyon itself. This is that same canyon on a more intimate scale and among the tourists taking selfies there are also joggers from Page who come simply to marvel at nature’s signature, carved deep into the earth. Standing on the precipice, it’s easy to understand what Baya means when she explains why the Navajo have stayed in this place for so long. ‘This land,’ she says, ‘has its own special power.’

Take US-89 south to Flagstaff and then switch to US-89A for the scenic drive through the valley to Sedona. The trip will take around three hours.

5. Sedona & the Verde Valley

Reap the harvest of Arizona’s growing wine scene and dine beneath majestic red rocks

It’s early on Sunday afternoon and winemaker Eric Glomski is welcoming guests to Page Springs Cellars. Some have come to enjoy the sunshine on a stroll through the vineyards, but most are here to while away the hours on the top deck of the cellar, uncorking bottles to taste the fruits of the fields that stretch out below.

Eric is something of a viticultural celebrity in these parts. He used to run the Arizona Stronghold winery with an actual rock star, Tool frontman Maynard James Keenan, and he bought the Page Springs Cellars site in 2003. Wandering into the vineyards past the fast-flowing brook which gives the winery its name, you’d be forgiven for thinking you’re in Burgundy in France or Portugal’s Douro Valley.

‘Everyone asks, isn’t it too hot and dry in Arizona to grow grapes?’ says Eric. ‘I remind them that grapes originated in the Middle East, Lebanon and Syria, so they’re very adaptive. There are different microclimates throughout the state. If I were to liken us to anywhere, in terms of climate, we’re closest to parts of Spain, France and Italy – some of the homelands of grape growing.’

So, here in the Verde Valley, Eric finds terroir to suit the grapes. One side has limestone soil, just as at Châteauneuf-du- Pape in France, while the other side is volcanic, like on Sicily’s Mount Etna. ‘We’re also trying new things,’ he says. ‘Just because it works somewhere else doesn’t mean it will work here.’

So far, something is working. This is just one of 22 vineyards that have sprung up in the valley to feed Arizona’s burgeoning wine scene. Perhaps the most scenic is Barbara Predmore’s Alcantara vineyard at the confluence of the Verde River and Oak Creek, where she also hosts weddings at a palatial villa that looks like it’s been transported wholesale from Ancient Rome.

While the grapes may be grown down here, most of it seems to get drunk up the valley in Sedona. Here the landscape changes again, adding imposing red rock formations that rise from the earth like Martian mountains and have attracted ambitious climbers for decades.

It’s not just the scenery that brings people to this laid-back town. New Age types have also long been attracted by the belief that benevolent swirling vortexes of ‘subtle energy’ emanate from the land. The result is a town with a thriving arts scene and plenty of vegetarian cafés, including Chocola Tree, where you can pick up a kale smoothie while recharging your crystals. The emphasis on organic, locally grown food extends to high-end restaurants, the star of the scene being Mariposa, a Latininspired grill. Chef Lisa Dahl has grown used to hearing about the impact Sedona’s panoramic views have on her customers. ‘I’ll never forget one guy telling me that sitting on the patio is like being on the ocean,’ she says. ‘There’s a level of serenity you feel here that’s overwhelming.’ As Lisa heads back to the kitchen, burgers, tostadas, cocktails and local wine appear. Maybe there’s something to these swirling energy vortexes after all.

Published in Lonely Planet Traveller, March 2017.

It was midnight on Monday the 11th of April, 2016. Fourteen-year-old Lucas Markham had set out for his girlfriend Kim Edwards’ house on Dawson Avenue in the small market town of Spalding, Lincolnshire. In his backpack, rolled inside a black T-shirt, were four kitchen knives. When he arrived at the back of the house, he clambered onto the roof of a shed and knocked three times on her bedroom window. He waited, but before long he realised that Kim, who was also 14, was fast asleep. Lucas walked back home alone.

It was midnight on Monday the 11th of April, 2016. Fourteen-year-old Lucas Markham had set out for his girlfriend Kim Edwards’ house on Dawson Avenue in the small market town of Spalding, Lincolnshire. In his backpack, rolled inside a black T-shirt, were four kitchen knives. When he arrived at the back of the house, he clambered onto the roof of a shed and knocked three times on her bedroom window. He waited, but before long he realised that Kim, who was also 14, was fast asleep. Lucas walked back home alone.

It was 9:30AM on an uncomfortably hot Friday morning, and in the gallery of Court 10 at the Old Bailey Antonitza Smith sat alone. Below her, flanked by guards and wearing the navy-blue suit she had delivered to him at Belmarsh Prison, was her only son, Damon. The 20-year-old’s curly hair had been cut short. They were both waiting to learn the sentence that the judge, Richard Marks QC, would hand down that morning.

It was 9:30AM on an uncomfortably hot Friday morning, and in the gallery of Court 10 at the Old Bailey Antonitza Smith sat alone. Below her, flanked by guards and wearing the navy-blue suit she had delivered to him at Belmarsh Prison, was her only son, Damon. The 20-year-old’s curly hair had been cut short. They were both waiting to learn the sentence that the judge, Richard Marks QC, would hand down that morning.

Helal al Baarini is 21 years old and a native of Homs, Syria. He fled to Jordan in 2012 and came to England in February 2016.

Helal al Baarini is 21 years old and a native of Homs, Syria. He fled to Jordan in 2012 and came to England in February 2016.

Douglas Adams was many things: a novel writer, a radio-maker, a sane man in an increasingly insane universe, but most of all he was a hoopy frood who really knew where his towel was.

Douglas Adams was many things: a novel writer, a radio-maker, a sane man in an increasingly insane universe, but most of all he was a hoopy frood who really knew where his towel was.

I

I

“You know, I’m automatically attracted to beautiful – I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.”

“You know, I’m automatically attracted to beautiful – I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.”

18-year-old Eli Aldridge has been selected as a Labour candidate for the General Election on 8 June – a day after his A Level exams start. The aspiring MP for Westmorland & Lonsdale explains how you too could get started on the road to Westminster

18-year-old Eli Aldridge has been selected as a Labour candidate for the General Election on 8 June – a day after his A Level exams start. The aspiring MP for Westmorland & Lonsdale explains how you too could get started on the road to Westminster

B

B

A lot of British guitar bands these days are just so bait,” says The Magic Gang bassist Gus Taylor (it means ‘obvious’, for anyone over the age of 30). “They may throw in a massive riff, but what they’re doing isn’t very – what’s the word? – tasteful. Ten years ago we had a really good indie scene in the UK, but there hasn’t been much that’s mattered since then.”

A lot of British guitar bands these days are just so bait,” says The Magic Gang bassist Gus Taylor (it means ‘obvious’, for anyone over the age of 30). “They may throw in a massive riff, but what they’re doing isn’t very – what’s the word? – tasteful. Ten years ago we had a really good indie scene in the UK, but there hasn’t been much that’s mattered since then.”

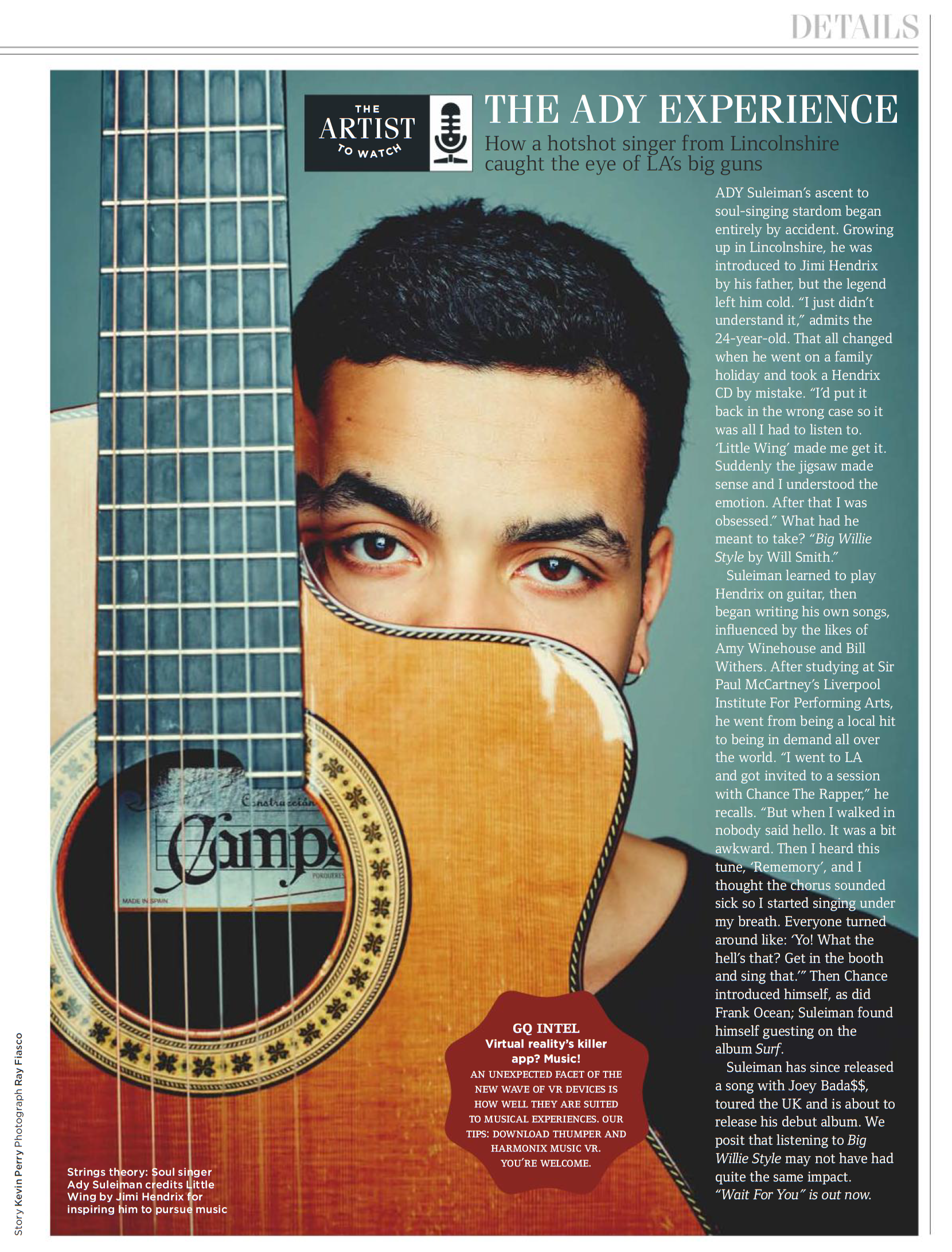

Published in British GQ, May 2017.

Published in British GQ, May 2017.

When Detective Sergeant Steve Fulcher heard that taxi driver Christopher Halliwell – the lead suspect in the disappearance of Sian O’Callaghan five days earlier – had refused to tell officers anything during his arrest, he made a decision that, in a cop show, would be described as “not doing things by the book”. In the real world, Fulcher’s actions were later described by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) as a “catastrophic” breach of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act.

When Detective Sergeant Steve Fulcher heard that taxi driver Christopher Halliwell – the lead suspect in the disappearance of Sian O’Callaghan five days earlier – had refused to tell officers anything during his arrest, he made a decision that, in a cop show, would be described as “not doing things by the book”. In the real world, Fulcher’s actions were later described by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) as a “catastrophic” breach of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act.

Kualoa Ranch is a 4000-acre private nature reserve in Hawaii, most recognisable as Jurassic Park. Back in December 2015, I flew over to witness its transformation into Skull Island, a place where King Kong meets Apocalypse Now. Tom Hiddleston and director Jordan Vogt-Roberts were on hand to explain:

Kualoa Ranch is a 4000-acre private nature reserve in Hawaii, most recognisable as Jurassic Park. Back in December 2015, I flew over to witness its transformation into Skull Island, a place where King Kong meets Apocalypse Now. Tom Hiddleston and director Jordan Vogt-Roberts were on hand to explain:

Published in British GQ, April 2017.

Published in British GQ, April 2017.

When the smell of rotting human flesh became too much for the residents of Block E to take, the caretaker on The Peabody Estate first tried to mask it with bubblegum-scented air spray. When that didn’t work, somebody eventually decided to call the police.

When the smell of rotting human flesh became too much for the residents of Block E to take, the caretaker on The Peabody Estate first tried to mask it with bubblegum-scented air spray. When that didn’t work, somebody eventually decided to call the police.

The other day I found myself watching Central Intelligence, a 2016 goofball action romp starring Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as a unicorn-loving super-spy who saves the world by teaming up—for reasons which are still not altogether clear to me—with his old schoolmate, an accountant played by Kevin Hart. Look, I know it’s not going to win any Oscars but I was on a plane at the time. Nobody wants to strap in to 12 Years A Slave at 35,000 feet. Anyway, there’s a scene where the pair jump out of a skyscraper together through a plate glass window in a hail of bullets. I’m sure you know the type, whether or not you’ve had the pleasure of Central Intelligence. As the glass shatters and they burst into the air, the voice you hear isn’t The Rock’s or Kevin Hart’s, but the sheer, uncut exhilaration of Damon Albarn screaming: “WOOOO-HOOOOO!” It’s a dumb moment in a dumb film, but hearing “Song 2” in a Hollywood blockbuster almost exactly 20 years after it first came out was a weird and timely reminder of what a transformative impact that song, and the self-titled album it appears on, had on Blur’s relationship with America and their whole career.

The other day I found myself watching Central Intelligence, a 2016 goofball action romp starring Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as a unicorn-loving super-spy who saves the world by teaming up—for reasons which are still not altogether clear to me—with his old schoolmate, an accountant played by Kevin Hart. Look, I know it’s not going to win any Oscars but I was on a plane at the time. Nobody wants to strap in to 12 Years A Slave at 35,000 feet. Anyway, there’s a scene where the pair jump out of a skyscraper together through a plate glass window in a hail of bullets. I’m sure you know the type, whether or not you’ve had the pleasure of Central Intelligence. As the glass shatters and they burst into the air, the voice you hear isn’t The Rock’s or Kevin Hart’s, but the sheer, uncut exhilaration of Damon Albarn screaming: “WOOOO-HOOOOO!” It’s a dumb moment in a dumb film, but hearing “Song 2” in a Hollywood blockbuster almost exactly 20 years after it first came out was a weird and timely reminder of what a transformative impact that song, and the self-titled album it appears on, had on Blur’s relationship with America and their whole career.

You can get a lot of things for free on the NHS, but a five foot cylinder of nitrous oxide isn’t supposed to be one them. Mind you, that hasn’t stopped plenty of people figuring out that stealing NOS cylinders from hospitals in order to sell the gas in balloons at parties, festivals and raves can be a highly lucrative venture. With punters happy to spend £2 to £5 on each balloon, even a smaller 3ft cylinder can be converted into about £700 of pure profit.

You can get a lot of things for free on the NHS, but a five foot cylinder of nitrous oxide isn’t supposed to be one them. Mind you, that hasn’t stopped plenty of people figuring out that stealing NOS cylinders from hospitals in order to sell the gas in balloons at parties, festivals and raves can be a highly lucrative venture. With punters happy to spend £2 to £5 on each balloon, even a smaller 3ft cylinder can be converted into about £700 of pure profit.

This week, Donald Trump will place one of his tiny hands on the Bible and his puckered lips will accept the US presidency: the first Twitter troll with a nuclear arsenal. Holed up at a secret location in Nashville, preparing for a tour that’s due to come to the UK and Europe at the end of March, firebrand rap duo Run The Jewels are somehow managing to see the funny side.

This week, Donald Trump will place one of his tiny hands on the Bible and his puckered lips will accept the US presidency: the first Twitter troll with a nuclear arsenal. Holed up at a secret location in Nashville, preparing for a tour that’s due to come to the UK and Europe at the end of March, firebrand rap duo Run The Jewels are somehow managing to see the funny side.

It’s almost a surprise that Wayne Coyne doesn’t roll up to our interview in his giant hamster ball. The Flaming Lips frontman is so defined in his Wayne Coyne-ness that, waiting around, it’s hard not to picture him as he appears onstage: an intergalactic pirate smothered with fake blood and confetti, flanked by dancing pandas, his boulder-sized fists raised aloft to shoot green lasers into the sky. This is a man whose life is such a carnival of oddness that he’ll sometimes forget he’s carrying a solid gold hand grenade, which didn’t go over well when he took it through customs at Oklahoma City’s airport back in 2012. When he wanders into the lounge of his Clerkenwell hotel engulfed in a baggy hoodie, he can’t help but seem down to earth measured against his reputation. Despite the glitter in his snowy ringlets and the glue-on plastic diamonds studded around his right eye, he’s human after all.

It’s almost a surprise that Wayne Coyne doesn’t roll up to our interview in his giant hamster ball. The Flaming Lips frontman is so defined in his Wayne Coyne-ness that, waiting around, it’s hard not to picture him as he appears onstage: an intergalactic pirate smothered with fake blood and confetti, flanked by dancing pandas, his boulder-sized fists raised aloft to shoot green lasers into the sky. This is a man whose life is such a carnival of oddness that he’ll sometimes forget he’s carrying a solid gold hand grenade, which didn’t go over well when he took it through customs at Oklahoma City’s airport back in 2012. When he wanders into the lounge of his Clerkenwell hotel engulfed in a baggy hoodie, he can’t help but seem down to earth measured against his reputation. Despite the glitter in his snowy ringlets and the glue-on plastic diamonds studded around his right eye, he’s human after all.

Published in British GQ, February 2017.

Published in British GQ, February 2017.

Published in British GQ, February 2017.

Published in British GQ, February 2017.

We live in a “post-truth” world now, don’t we? You know it, Donald Trump knows it, even the lexicographers charged with keeping dictionaries hip know it. But while we might know it, many of us still don’t fully understand it. How can such a large chunk of the voting population just not give a fuck about the facts?

We live in a “post-truth” world now, don’t we? You know it, Donald Trump knows it, even the lexicographers charged with keeping dictionaries hip know it. But while we might know it, many of us still don’t fully understand it. How can such a large chunk of the voting population just not give a fuck about the facts?

There are certain moments that can change the course of a person’s life. For Adam Driver, it was being asked to kill Han Solo.

There are certain moments that can change the course of a person’s life. For Adam Driver, it was being asked to kill Han Solo.

Published in British GQ, January 2017.

Published in British GQ, January 2017.

A lot of us have had a rough time in 2016, but spare a thought this Christmas for the families of the poor men and women of the once proud legal highs industry. There’ll be no presents under the tree for their kids this year, not since the Roflcopter factories were shuttered and all the Meow Meow labs closed down. Things just haven’t been the same since the 26th of May this year, when the Psychoactive Substances Act came into effect, banning the sale of legal highs in the UK.

A lot of us have had a rough time in 2016, but spare a thought this Christmas for the families of the poor men and women of the once proud legal highs industry. There’ll be no presents under the tree for their kids this year, not since the Roflcopter factories were shuttered and all the Meow Meow labs closed down. Things just haven’t been the same since the 26th of May this year, when the Psychoactive Substances Act came into effect, banning the sale of legal highs in the UK.

What with all the time-consuming acid trips and having to grow your hair long, psych-rock hasn’t generally attracted a lot of people with a strong Protestant work ethic. That’s at least until bizarrely titled Melbourne seven-piece King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard gave the genre a shot in the arm and made everyone else look downright idle by releasing eight records in the last four years. Now they’ve upped the ante even further, announcing that in 2017 they’ll release no fewer than five new albums.

What with all the time-consuming acid trips and having to grow your hair long, psych-rock hasn’t generally attracted a lot of people with a strong Protestant work ethic. That’s at least until bizarrely titled Melbourne seven-piece King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard gave the genre a shot in the arm and made everyone else look downright idle by releasing eight records in the last four years. Now they’ve upped the ante even further, announcing that in 2017 they’ll release no fewer than five new albums.

Because of you I grew up wanting to drink martinis in exotic locations. Was being James Bond as much fun as it looked?

Because of you I grew up wanting to drink martinis in exotic locations. Was being James Bond as much fun as it looked?