Category Archives: Other

Kevin Perry Goes Large In The Med’s New Party Capital, Malta

If you work for the tourist board of a small Mediterranean island, British clubbers are presumably seen as something of a mixed blessing. Sure, they’re going to fill your hotels, eat at your restaurants and buy enough sambuca to double your GDP, but they’re also going to get lairy, keep their soundsystems going until 4am and end up performing drunken sex acts on your picturesque cobbled streets.

If you work for the tourist board of a small Mediterranean island, British clubbers are presumably seen as something of a mixed blessing. Sure, they’re going to fill your hotels, eat at your restaurants and buy enough sambuca to double your GDP, but they’re also going to get lairy, keep their soundsystems going until 4am and end up performing drunken sex acts on your picturesque cobbled streets.

It’s a chance Malta were willing to take this Easter when they invited Annie Mac to put on the inaugural Lost & Found festival over the long weekend. The island is no stranger to hard-partying Brits. Oliver Reed died of a heart attack here in 1999 at the age of 61 after drinking eight beers, three bottles of rum, a few rounds of whiskeys and a couple of cognacs – all the while beating five Royal Navy sailors at arm-wrestling. It’s a miracle they’ve got any booze left at all.

Horizon Festival 2015

It’s snowing so much in Bansko, Bulgaria that even ‘12 Inches Of Snow’ feels like an inadequate soundtrack. It’s more like ‘3 Feet High And Rising’. That’s good news for Horizon Festival, which has taken over the town for a week. Ask any adrenaline junkie and they’ll tell you there’s nothing quite like skiing on a mountain of pure, white powder.

It’s snowing so much in Bansko, Bulgaria that even ‘12 Inches Of Snow’ feels like an inadequate soundtrack. It’s more like ‘3 Feet High And Rising’. That’s good news for Horizon Festival, which has taken over the town for a week. Ask any adrenaline junkie and they’ll tell you there’s nothing quite like skiing on a mountain of pure, white powder.

The festival’s main stage, Mountain Creek, springs up beside the slope towards the bottom of Bansko’s sublime main ski run. This means on the opening Sunday afternoon you could ski right into Craig Charles’ two hour funk and soul set, get some ‘Sexual Healing’, then just coast back to town.

After a hard day on the piste and on the piss, the festival keeps the party going long into the wee small hours by taking over a host of Bansko nightclubs and filling them with a well-shuffled pack of DJs. First up there’s Jack’s House, where barmaids light cigarettes and shots with flamethrowers while the likes of Bulgarian native Nick Nikolov and Brits like Paleman and El-B chart a course from euphoric house to classic garage.

Just round the corner there’s Oxygen, a tiny, packed sweatbox where Om Unit lays down furious drum and bass while a guy with a t-shirt saying ‘Laughing Gaz’ is selling nitrous and giggling all the way to the bank. The festival even takes over a couple of Go Go clubs, like the Red Rose ‘Erotic Dance Club’. You haven’t really experienced Eastern European debauchery until you’ve seen strippers hassle startled dance music heads, but the real action is behind the decks where The Menendez Brothers and Benton bring an old school jungle vibe to proceedings. It ain’t what the Go Go girls usually dance to, that’s for sure.

The jewel in Horizon’s crown is Gardenia. Located beneath an unassuming hotel where many of the festival’s artists stay is a serious sound system with a dream dancefloor. The line-up is just as good, with LA hip-hop hero and 808 king Egyptian Lover going back to back with local live techno legend KiNK until 5am on the opening night. The slopes will be open again in just a few hours. No rest for the wicked.

For Mixmag.

Inside Kink.com’s San Francisco Porn Palace

The basement of the San Francisco Armory used to be where the National Guard kept their guns and ammo. If you go there now you’ll see a chainsaw with all the sharp edges replaced with plastic tongues, a room full of dildos attached to drills and two bright blue 55 gallon barrels of Passion-brand natural water-based lube. One hundred and ten gallons is a hell of a lot of lube.

The basement of the San Francisco Armory used to be where the National Guard kept their guns and ammo. If you go there now you’ll see a chainsaw with all the sharp edges replaced with plastic tongues, a room full of dildos attached to drills and two bright blue 55 gallon barrels of Passion-brand natural water-based lube. One hundred and ten gallons is a hell of a lot of lube.

Ghost Culture

“I might not bring out the feather boas just yet,” says James Greenwood, who’s plotting his live debut as Ghost Culture, “but there’s an element of theatrics. I want people to think about dance music in a different way. It doesn’t have to be overly macho. It can be a performance.”

Greenwood is used to following his own path. When he left school at 18 he skipped university and went straight to hustling for work at studios and record shops. “I would get the train in from Essex and go to Pure Groove,” he says. “I wasn’t officially working there, I was just pretending I could do sound for their live bands.”

After meeting Daniel Avery there, Greenwood wound up engineering ‘Drone Logic’ – but he wasn’t satisfied with that. “I had this little glint in my eye,” he says. “I wanted to be writing.”

He’d been working on Ghost Culture for three years and now had the chance to finish his own album – with a very specific sonic template. “For the two months I was finishing the record I made a conscious effort to only listen to three records,” he says. “‘Fear of Music’ by Talking Heads, ‘Construction Time Again’ by Depeche Mode and ‘Ziggy Stardust’ by David Bowie. I didn’t want to feel like I was in competition with whatever was on Pitchfork that week.”

That refusal to follow trends marks him apart. “I’m passionate about sticking to the sound that’s in my head,” he says. “There’s too many paint-by-numbers things going around.”

Originally published in Mixmag, February 2015.

Wealthy American Women Can’t Resist Cuba’s Young, Salsa Dancing Male Hustlers

The deaf prostitute took my hand in hers and traced “20” on my palm with her finger. When I look back on all my nights out, it’s a moment more depressing than even a wet Tuesday in Torquay could muster. I’d bumped into her down on the corner in front of Havana’s faded Hotel Nacional, former stomping ground of Sinatra, Hemingway and Brando and host to the infamous Mafia conference in 1946 that Coppola recreated inGodfather II. All I’d done was ask her for directions. I shook my head and tried to mime: “Sorry for wasting your time”.

The deaf prostitute took my hand in hers and traced “20” on my palm with her finger. When I look back on all my nights out, it’s a moment more depressing than even a wet Tuesday in Torquay could muster. I’d bumped into her down on the corner in front of Havana’s faded Hotel Nacional, former stomping ground of Sinatra, Hemingway and Brando and host to the infamous Mafia conference in 1946 that Coppola recreated inGodfather II. All I’d done was ask her for directions. I shook my head and tried to mime: “Sorry for wasting your time”.

It wouldn’t have been the first time a foreigner in Cuba was assumed to be in the market for transactional sex, and now that the USA and Cuba are friends again there’ll be a whole lot more of it. Thanks to the travel ban currently in place, only around 60,000 Americans visit Cuba each year. Jay-Z and Beyonce caused a minor diplomatic incident when they went this summer, and they’re the closest things the Yanks have to infallible royalty. The US figure is dwarfed by the 150,000 Brits and more than a million Canadians who are drawn there by the promise of sun, rum and hot, steamy salsa dancing.

11 Outstanding Cocktail Bars In London

There are enough great pubs in London to keep the ghosts of Oliver Reed and Peter O’Toole busy for weeks, not to mention plenty of heaving nightclubs willing to sell you an overpriced spirit and mixer. However, finding a really top-class cocktail in the city requires a little insider knowledge. The best places are tucked away, safe in the knowledge that only the truly discerning drinker will seek them out. And since we know you, dear reader, are one of those discerning drinkers, I’m going to give you a tour of the best cocktail bars in the city.

There are enough great pubs in London to keep the ghosts of Oliver Reed and Peter O’Toole busy for weeks, not to mention plenty of heaving nightclubs willing to sell you an overpriced spirit and mixer. However, finding a really top-class cocktail in the city requires a little insider knowledge. The best places are tucked away, safe in the knowledge that only the truly discerning drinker will seek them out. And since we know you, dear reader, are one of those discerning drinkers, I’m going to give you a tour of the best cocktail bars in the city.

Inside Britain’s Secret Courts

The Investigatory Powers Tribunals (IPT) are the most secretive court cases in Britain. They are the only place you can go and complain if you think you’re being illegally spied on by MI5, MI6 or GCHQ, or even by the police or local government. The only time they’ve actually found against the authorities was when Poole Borough Council spied on a family to see if they were lying about which school catchment area they lived in. Of course before you can make a complaint you have to somehow know that you’re being secretly spied on, which is pretty tricky. Even if you do, the IPT most likely won’t grant you access to the evidence against you, give you the right to cross-examine anyone, let you appeal or even tell you what their reasoning was when they hand down their verdict. Sometimes they won’t even tell you whether you’ve won or not. Needless to say, they almost always meet behind closed doors.

The Investigatory Powers Tribunals (IPT) are the most secretive court cases in Britain. They are the only place you can go and complain if you think you’re being illegally spied on by MI5, MI6 or GCHQ, or even by the police or local government. The only time they’ve actually found against the authorities was when Poole Borough Council spied on a family to see if they were lying about which school catchment area they lived in. Of course before you can make a complaint you have to somehow know that you’re being secretly spied on, which is pretty tricky. Even if you do, the IPT most likely won’t grant you access to the evidence against you, give you the right to cross-examine anyone, let you appeal or even tell you what their reasoning was when they hand down their verdict. Sometimes they won’t even tell you whether you’ve won or not. Needless to say, they almost always meet behind closed doors.

That was until this year, when the IPT bowed to legal pressure and agreed to open its doors for a few select public hearings. Which is how I found myself, a couple of weeks ago, at the Rolls Building in Holborn, central London at 4:30PM on a dreary Wednesday afternoon.

Clough Williams-Ellis: The Things That Dreams Are Made Of

Clough Williams-Ellis, the man who conjured Portmeirion into existence, was a dreamer all his life. In his youth the second son of the Reverend John Clough Williams-Ellis imagined another life for himself. “As a child I just lamented that my lot was cast in Victorian non-conformist Wales instead in some such sparkling city as decadent 18th Century Venice,” he later remembered.

Clough Williams-Ellis, the man who conjured Portmeirion into existence, was a dreamer all his life. In his youth the second son of the Reverend John Clough Williams-Ellis imagined another life for himself. “As a child I just lamented that my lot was cast in Victorian non-conformist Wales instead in some such sparkling city as decadent 18th Century Venice,” he later remembered.

Full piece in British Ideas Corporation, Festival No. 6 Special

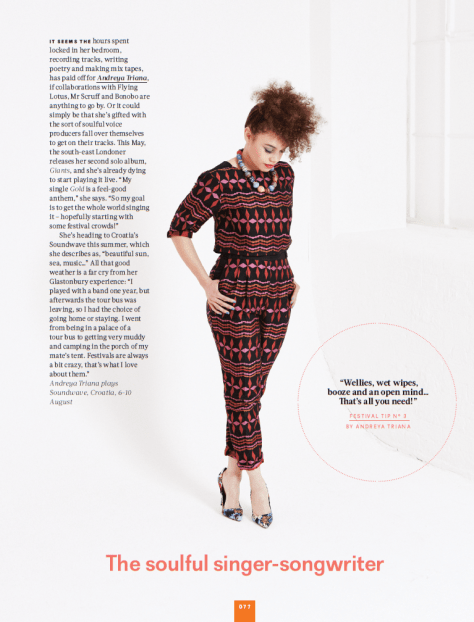

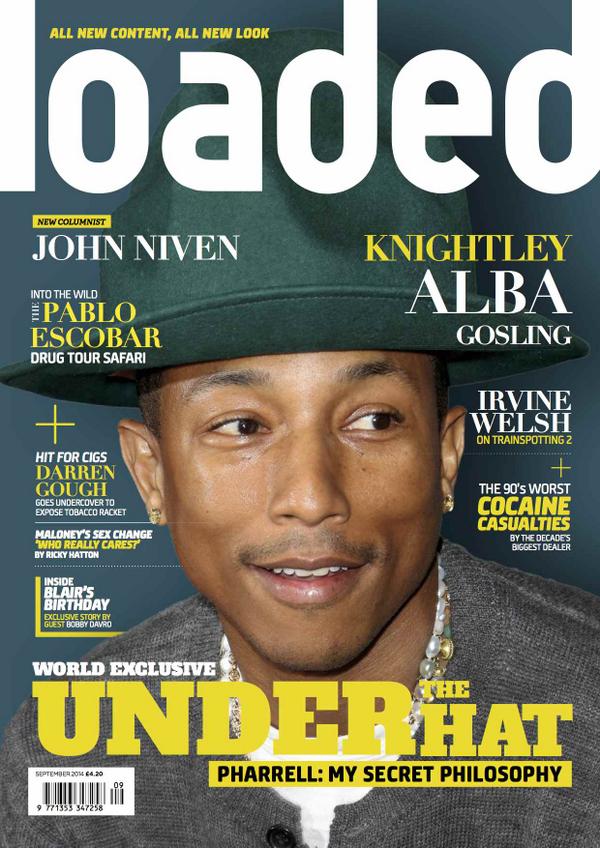

Under The Hat: Pharrell’s Secret Philosophy

HE’S not just a pretty (expensive) hat. Pharrell Williams believes he’s tuned into how we’ll be curing diseases in the future. You see, music isn’t a matter of life and death to him – it’s much more important than that. On a flying visit to London the most successful and ubiquitous producer of his generation took the time to explain his philosophy to Loaded. “I believe in the medicinal property of music,” he tells us. “I believe in maximising the therapeutic and holistic properties of music and what it can do for you.”

Replacing medicine with melodies might sound far-fetched, but as well as having three million-selling UK singles in the last year alone, Pharrell is also a scholar of world musical traditions. “The Tibetans have singing bowls that they tune chakras with,” he points out, referring to the Buddhist belief that upturned bells of different pitches can affect the body’s seven energy points. “In the Western world there are certain songs that come on and make people feel better. When people are feeling melancholy and down and they need something to relate to they can play a blues record and it can help purge them and get those feelings out. There are such incredible degrees of music, frequency-wise, that I believe science will prove that we’ll be able to use exact musical notes to cure certain things.”

It isn’t hard to see how Pharrell’s unreserved faith in the power of music has made him the man he is in 2014. He’s on a run of singles which make him the envy of every other songwriter and producer on the planet – and he’s done it a full decade after he last dominated pop music. At 41, Pharrell Williams is having the year of his life.

I FIRST spoke to Pharrell back in April 2013, at the start of his annus mirabilis. I was in California attending Coachella in the company of Daft Punk, who were at the festival to premiere the video for their omnipresent global hit ‘Get Lucky’ on the big screens. In typical Daft Punk fashion the stunt was completely unannounced, so when the video first burst into life showing Pharrell fronting a fantasy band with Nile Rodgers on guitar and the robots on bass and drums, half the festival sprinted across the field thinking they were about to catch an impromptu live set. In truth, Daft Punk’s Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo were down the front of the VIP area, unrecognizable without their helmets, watching amongst the crowd with wide grins splayed across their faces.

The next day, Daft Punk hosted a party at the house they were renting in Palm Springs: Bing Crosby’s former villa, where JFK and Marilyn Monroe are said to have consummated their affair. As the piña coladas flowed, Bangalter explained to me why they’d chosen Pharrell to front the band he described as being their “dream scenario in a dream environment”. “We’re fans of hip-hop and Pharrell as a performer, as a singer, as a rapper and as a human being is someone who we consider to be extremely special,” he said. “It felt like a perfect match for creating this one-time band with Nile and the robots. It was exciting on a musical level and a symbolic level. Most of all, his talent as singer and a performer made him the perfect candidate for us.”

Nile Rodgers, the legendary Chic guitarist and producer of hits for the likes of David Bowie, Madonna and Mick Jagger is arguably the man whose career Pharrell has most modeled his own on. He was similarly full of praise for his new collaborator. “Sometimes you meet a person and you have an idea of who they are but then you meet them and they go beyond it,” Rodgers told me. “I love Pharrell. As a person, as an artist, as a human being, he went way beyond any preconceived notion I had of him, which was already pretty cool! He had done a record that really paid homage to me, with Justin Timberlake. I remember meeting him at the Grammys and he walked up on me and just bowed down and said: “Hey man, I’m sorry but I couldn’t help it.” I said: “Dude, don’t worry! If you don’t think I stole ‘Good Times’ from somebody else you’re crazy!” ‘Good Times’ was not a completely original idea by any stretch of the imagination! When we finally got the chance to work together and we got to talk I thought to myself: “I love this dude!” He’s unbelievably cool.”

Pharrell himself didn’t make it to Daft Punk’s pool party. He was at home in Miami, where his exhausted-sounding manager told me he was producing two different artists simultaneously. When I called him from California he was unusually taciturn. It tells you something about Pharrell’s sweetness of character that despite the fact Bangalter and de Homem-Christo were splashing around in their trunks in front of me, Pharrell was still earnestly referring to them as “the robots”. “I’m very excited for the robots, man,” he said, speaking about the anticipation for their record ‘Random Access Memories’. “They deserve it. Those guys are super-rare. This is all a part of their masterful calculation. I’m thankful to just be a digit in their equation. I’m such a small part. I was just happy to be there and be a part of it. I’m just as much a voyeur of their process as you are.”

When I told him about Nile Rodgers’ tribute to him, Pharrell was effusive in returning the praise. “I was pleasantly surprised that Daft Punk got him to work on the album because I had been working on music previously that was imitating him. It was the coolest thing. His playing is exquisite. He’s just a genius.”

With Pharrell and Rodgers together at last, ‘Get Lucky’ was unstoppable. It hit the top ten in over 32 countries, and for a while it seemed impossible to go to a nightclub anywhere on earth without hearing it. I personally saw people getting down to it on dancefloors everywhere from Lilongwe in Malawi to Bogota, Colombia. It picked up Grammys for both Record of the Year and Best Pop Duo/Group Performance, and at the ceremony in January this year Pharrell, Rodgers and Daft Punk were joined by Stevie Wonder to perform their hit. In sales terms it shifted 9.3 million copies, making it one of 2013’s biggest singles. But not the biggest. That would be Robin Thicke’s Pharrell-produced ‘Blurred Lines’, which sold 14.8 million copies. Solo hit ‘Happy’ sold another 10 million. By the end of 2013, Pharrell was only really competing against himself. The internet was supposed to have divided us all into specific camps, atomizing popular music and ending the era of this kind of ubiquitous super-hit. To understand how Pharrell bucked that trend, we have to go right back to the beginning.

PHARRELL Williams was born on 5th April 1973 in the east coast city of Virginia Beach, a seven hour drive south of New York City. The eldest of three sons born to Southern handyman Pharaoh Williams and his wife Carolyn, a teacher. “My mum thought her sons could do no wrong. She lived for us,” he told the Evening Standard in 2012. “There was plenty of discipline, but we knew we were loved. My dad is a nice guy, Southern, old-fashioned. He restores cars now. My mum has just gotten her doctorate in education.”

At age 12 Pharrell met his future production partner Chad Hugo at a summer band camp where he was playing keyboards and drums while Hugo played saxophone. The pair soon became just as interested in production as in playing their instruments. “I was a teenager and we were desperately making music, Chad and I,” he remembered later. “We loved taking Depeche Mode and A Tribe Called Quest tracks and recreating them, taking them apart and figuring out how those things worked. It was kind of cool because that’s what we’d do every day after school.”

Outside of music, Pharrell was always the kid with his head in the stars. From a young age he was bewitched by the astrophysicist Carl Sagan’s groundbreaking documentary series ‘Cosmos’. “I can only aspire to be someone that people learn as much from as they’ve learned from Carl Sagan,” he would say later. “Carl Sagan is to me what Tribe Called Quest was to us for music.”

Eventually he had Chad formed an R&B band called The Neptunes with Shay Haley, who would stay with them after they became N.E.R.D, and schoolmate Mike Etheridge. It was after a high school talent show performance that the young band came to the attention of the producer Teddy Riley, who Pharrell says “pretty much changed my life.” “His studio was like a five minute from my high school,” he said later. “He sent a scout over and they saw us and the rest was history.”

Riley, a member of R&B group Blackstreet as well as a Grammy-winning producer for the likes of Michael Jackson and Usher, took Pharrell and Chad Hugo under his wing. However, it took a while for the young, excitable Pharrell to get a hang of the discipline of record production. He made a nuisance of himself until one of Riley’s engineers took him to one side for a quiet talking to. “Teddy had layers of people around him in his compound,” remembered Pharrell, speaking to the Canadian interviewer Nardwuar. “Some of the engineers were cool and some were not so nice. They meant business. They didn’t want kids running round the studio getting in the way, and quite honestly that’s probably what we did. My studio etiquette when I first came to the studio was so wrong. Teddy would play a chord and I’d shout: ‘Hey, why don’t you change it to this chord?’ The engineer would just look at me and give me the dirtiest look. I’ll never forget, a guy called Jean Marie gave me the best lesson in the world. He sat me down and said: ‘Look, Teddy’s the boss. When he’s working, you don’t say anything. You’re lucky to be in the room. You sit quiet and you listen to everything that he’s doing. You absorb everything that you can. When you have the opportunity to ask him a question, you ask him a question, but you don’t just jump out. You’ve got to have better studio etiquette than this. I believe in you, and I see what Teddy sees in you and Chad, but you have to calm down.’ Chad was quiet. Chad wouldn’t say anything, but I was like the young, hot-headed, fiery Aries. I’d be going: ‘Change that chord! Change the snare!’ They were like: ‘Pipe down!’”

Pharrell’s first ever writing credit came in 1992, when he was just 19. He wrote a verse for Riley to perform on Wreckx-N-Effect’s hit ‘Rump Shaker’. “I remember being a kid in high school and I was definitely unfocused,” he said later. “I had another year to go, and when that record came out it was an amazing feeling. I was from Virginia Beach, Virginia, where there wasn’t really a music industry at all.” Later that same year he made his debut vocal appearance on a record, chanting “S-W-V” towards the end of a remix of girl group SWV’s track ‘Right Here’.

Success didn’t come overnight, but Pharrell kept his head down and worked under the tutelage of Riley, bouncing ideas off his partner Hugo. The pair dusted off their old band’s name, The Neptunes, and started using it for their own production work. When Riley’s group Blackstreet released their debut self-titled record in 1994, The Neptunes were credited as co-producers on album track ‘Tonight’s The Night’. Over the next couple of years, the duo produced a handful of other singles as they searched for a sound they could call their own. They found it in 1998, working on a track called ‘Superthug’ for the rapper Noreaga. The single hit number 36 on the Billboard charts, but more importantly for Pharrell and Chad Hugo it introduced the world to ‘The Neptunes sound’. In 1999, a mutual friend introduced the pair to a 20-year-old aspiring singer named Kelis Rogers. They never looked back.

KELIS and Pharrell hit it off immediately. The Neptunes had been invited to produce a track for Ol’ Dirty Bastard, a founding member of the Wu-Tang Clan, and they came up with the possibly lunatic idea of pairing the fearsome rapper’s rasp with the debutant singer’s sultry hook. The result was magic. ‘Got Your Money’ sounded like nothing else before or since, and the single announced Kelis as a major new talent.

They followed that up with an album ‘Kaleidoscope’ which included ‘Caught Out There’, featuring Kelis’ unforgettable shouted “I hate you so much right now” refrain. It peaked at number four, giving The Neptunes their first hit here in the UK. Meanwhile, things were getting complicated outside the studio for Pharrell and Kelis, who had become involved. “We never dated,” she clarified in a 2012 interview with Complex magazine. “We have the same relationship now that we did then, with the exception of the sexual part. I used to care too much. I began to feel that all men cheat. [I felt] all cynical and gross.”

The impact Kelis had on Pharrell’s life extended to his wardrobe. In a recent Vogue interview, he credited his interest in fashion to meeting her at this point in his life. “I’d just signed this girl called Kelis, and back then all I wore was Ralph Lauren’s Polo, because that was the thing,” he said. “And Kelis turned to me and said, ‘You’ve got to get out of this box.’ She introduced me to Prada and Gucci. It was thanks to Kelis I discovered a life outside of monograms.”

Follow-up single ‘Good Stuff’ (featuring Pusha T back when he was still calling himself Terrar) further refined their sound. Bigger artists were beginning to seek them out, and by the following year Jay-Z helped The Neptunes score their first US number one single with ‘I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me)’. It’s a mark of the respect they were now held in that Hova shouts them out on the track, promising to “Get you bling like the Neptune sound”, yet at the same time Pharrell was still so little known that despite singing the song’s chorus he was uncredited on the album sleeve and doesn’t even appear in the music video.

The time was coming for Pharrell to step out of the shadow of the production desk and into the limelight. 2001 saw the release of N.E.R.D’s debut album ‘In Search Of…’, named by the still space-obsessed Pharrell in honour of a supernatural TV show hosted by Leonard Nimoy. Originally released only in the UK, where Kelis’ Neptunes-produced records had fared better than in the States, the album was by Pharrell’s modern standards only a modest hit. Singles ‘Lapdance’ and ‘Rock Star’ edged into the Top 20, but they did serve to establish Pharrell as a frontman in his own right. Meanwhile their production work was producing bigger and bigger hits. The same month ‘In Search Of…’ hit the shelves, they had their first worldwide number one with Britney Spears’ ‘I’m A Slave 4 U’. Britney had hand-picked The Neptunes to work with after becoming obsessed with their work with Jay-Z.

Despite the phenomenal pace and quality of their output, Pharrell was still finding time to have fun. It was around this time that the lifelong non-smoker had his first serious experience with marijuana, which he had asking a friend to bake into brownies so he could try it without toking. He ate two, got the munchies and then ate four more. That’s when things got really trippy. “It was like straight-up, ‘Big Lebowski’ running from the bowling pins weird shit,” he remembered later. “I went to use the bathroom and passed out on the toilet.”

Maybe Pharrell should count himself lucky he didn’t take to heavy drug use. In 2002 the Neptunes were on a run of hit singles that remains pretty much unparalleled in modern times – well, at least until Pharrell did it again in 2013. In 2002 the duo were behind the desk for Nelly’s ‘Hot In Herre’, N’Sync’s ‘Girlfriend’, Beyoncé’s ‘Work It Out’, Busta Rhymes’ ‘Pass The Courvoisier, Part II’ and Britney’s ‘Boys’ to name but five. When Justin Timberlake wanted to go solo at the end of the year it was Pharrell he called. The Neptunes produced the bulk of his album ‘Justified’, including a trio of massive singles in ‘Señorita’, ‘Like I Love You’ and ‘Rock Your Body’. The following year, 2003, they were behind Snoop Dogg’s ‘Beautiful’, Kelis’ ‘Milkshake’ and Jay-Z’s ‘Change Clothes’. June also saw Pharrell release his first single as a solo artist with ‘Frontin’’, which featured Jay-Z and hit the top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic.

In 2004, N.E.R.D. released their second album, ‘Fly or Die’. As if to emphasise the point that everything was going Pharrell’s way, lead single ‘She Wants To Move’ starred Mis-Teeq singer Alesha Dixon who he’d apparently spotted in a magazine photoshoot and ended up dating. In September, Pharrell and Snoop released ‘Drop It Like It’s Hot’ which remained his biggest hit until 2013 and went on to be named the most popular rap song of the decade by Billboard. He wasn’t just making pop music anymore. By this point, Pharrell was pop music.

STAYING humble is pretty hard after a run like the one Pharrell was on. With the 2005 launch of his clothing line, Billionaire Boys Club, Pharrell was becoming a brand. When news emerged that he would release a debut solo record ‘In My Mind’ at the end of the year, expectations couldn’t have been higher. Alarm bells started to ring when he announced the record would be delayed because it still needed more work, and then disappeared for a full six months. When it was finally released in July 2006, it was met not with a bang but a critical whimper.

Looking back, Pharrell believes the album’s relative failure was due to an uncharacteristic failure to be true to himself. “‘In My Mind’ was just purpose-oriented toward, like, competing and being like my peers—the Jays and the Puffs of the world, who make great music,” he told GQ earlier this year. “But their purposes and their intentions are just completely different than what I have discovered in myself that I wanted to achieve in [second album G I R L].”

“I felt like I had amassed this big body of work, most—not all—but most of which was just about self-aggrandizement, and I wasn’t proud of it,” he added. “So I couldn’t be proud of the money that I had; I couldn’t be proud of all the stuff that I had. I was thankful, but what did it mean? What did I do? And at this point, where I came from, I’m just throwing it in that kid’s face, instead of saying, “Look at all the fish I have, and look how much we’re going to eat.” It should’ve been—at least a part of it—teaching them how to fish.”

After his single with Kanye West, the unfortunately named ‘Number One’ entered the American Billboard charts at a lowly 57, Pharrell began to take his eyes off music for a while. He kept busy, of course. There was still Billionaire Boys Club to run alongside his other clothing line, Ice Cream, and he also designed sunglasses for Louis Vuitton and “bulletproof”-inspired jackets for Moncler. He invested in an eco-friendly textile company, Bionic Yarn. He started his own YouTube channel called ‘i am OTHER’. In 2007 he dropped a cool $12.525 million on the 9,000 square foot penthouse apartment of Miami’s beachfront Bristol Tower. 40 floors up, the three-level apartment has its own pool – and Pharrell promptly decorated it like a Sixth Form common room, with huge Family Guy paintings and a Ms. Pac Man machine.

Perhaps the biggest change in Pharrell’s life occurred when girlfriend Helen Lasichanh – usually billed as a model/designer but in reality too secretive to be either – gave birth to their son Rocket in 2008. Fatherhood gave the once confirmed bachelor a new perspective on both life and the music he’d been making. “He’s changed my world,” he said, looking back. When one interviewer asked him how he’d changed, Pharrell replied with genuine humility: “My son teaches me. It’s crazy, he teaches me. This is one of those times in your life when you’re like, ‘Think about that one interview when someone asked you a serious question, and it just hit me…’ When you asked me about my son and my answer to you was, ‘He teaches me?’ Like, that was bizarre to me.”

N.E.R.D. released two more albums, 2008’s ‘Seeing Sounds’ and 2010’s ‘Nothing’ but they were met with little fanfare. Inspired by his young son, Pharrell produced the soundtrack to animated kids romp ‘Despicable Me’, which was at least received better reviews than either N.E.R.D album. After years as an innovator at music’s bleeding edge, Pharrell seemed destined to slide into family-friendly mediocrity.

In 2012, when Miley Cyrus began work on her fourth album, the one that she was hoping would reinvent her and cast off her squeaky-clean Disneyfied, Hannah Montana image for good, she wanted Pharrell to produce. Incredible as it seems now, her management team actually counseled her against it. He hadn’t had a hit in years. As far as they were concerned, he was all washed up.

MILEY got her way, as she usually does. She had seen how Pharrell’s production had helped Justin and Britney cast off their Disney pasts, but perhaps she also sensed that the time was right for a Pharrell renaissance. “Everything he did with, like, Justin and Britney made Pharrell a legend,” Miley would say. “But that wasn’t really his time.”

At the same time he was working with Miley on the album that would become ‘Bangerz’, Pharrell’s name was again beginning to appear in all the right places. 2012’s critical darling Frank Ocean fended off the overbearing approaches of Kanye West, but he was happy to work with the Neptunes man on ‘Channel Orange’ single ‘Sweet Life’. “To me he’s a singer/songwriter,” said Pharrell of the former Odd Future member. “But his album itself is incredible. He’s super talented. To me he’s like the Black James Taylor. He’s lyrical – he’s got a great perspective and super sick melodies. I haven’t seen anybody bob and weave through chords with such catchy melodies in a long time – that’s why I liked working with him.” Meanwhile the year’s breakthrough rap success story was Kendrick Lamar – and sure enough Pharrell was behind the desk for album track ‘good kid’.

It was late 2012 when Daft Punk invited Pharrell to Paris to hear the tracks that Nile Rodgers had already laid down for ‘Random Access Memories’. He’d been fans of, and friends with, “the robots” for 10 years by this point – ever since he first heard ‘One More Time’ while both acts were signed to Virgin Records. “It was just the emotion of that track,” he told me. “It’s great, emotional music.”

He described going into Daft Punk’s Parisian workshop as “magic”. Rather than discussing any of their previous work, he told me that they immediately started playing him Rodgers’ riffs to see what he’d come up with. “They just played me music and asked me to write to it,” he says. “It was an interesting back and forth. It was pretty cool.”

It’s tempting to think that Pharrell had himself in mind when he wrote the now famous opening line “Like the legend of the phoenix / All ends with beginnings”. After his meteoric rise and quiet fall back to earth, Pharrell’s star was very much back in the ascendancy again. Before July 2013, only 135 songs had sold more than a million copies in the entire history of the British charts. That month, Pharrell added two more when ‘Get Lucky’ and ‘Blurred Lines’ passed the milestone within weeks of each other.

He still wasn’t done. He had written a song called ‘Happy’ for CeeLo Green, but Green’s record label turned it down as the singer was due to release a Christmas album. Pharrell recorded it himself, released it on the soundtrack to ‘Despicable Me 2’, sold yet another million singles in the UK and scored himself an Oscar nomination to boot. “I’m still amazed with what people have done with ‘Happy’,” he said later. “At the end of the day I know that people like what I’m doing. But everything with that song has been done by the fans. When I hear it all the time on the radio and see it on TV it’s changed me because I realise all I can do is release a song and then what happens after that isn’t up to me.”

In a music industry we’re constantly being told is floundering, Forbes estimates that Pharrell earned $22 million between June 2013 and June 2014 and predicts that he’ll increase those earnings next year thanks to a meatier touring schedule. To commercial success add critical acclaim. In January 2014, Pharrell won four Grammys – more than he’d won in his entire career up to that point. This included the coveted Producer of the Year title – a full decade after he first won with The Neptunes. You wouldn’t have wanted to be the guy who had told Miley that Pharrell was a has-been that night.

GRAMMY wins are one thing, but all anyone was really talking about the next morning was Pharrell’s hat. The Vivienne Westwood buffalo hat he wore to the awards, last seen on Sex Pistols impresario Malcom McLaren circa 1982 became a meme overnight and showcased Pharrell’s idiosyncratic knack for using high fashion to make bold statements. His decision to wear it on the red carpet saw an immediate upsurge in interest that for a while knocked out Vivienne Westwood’s website completely. For a few months it became his signature style before, with impeccable timing, he realised the look had been done to death and auctioned the hat off to raise money for the children’s charity he set up with his mother. He denied his intention had ever been to stand out for the sake of it. “I don’t know that the aim should be to stand out,” he said. “I think the aim, well for me specifically, the aim would be to just express myself and be who I am and your clothing should be a byproduct of that.”

Pharrell must have realised that the cultural landscape of 2014 was vastly different to the one he first emerged onto a decade ago. While an awards ceremony hat being immediately transformed into a thousand Twitter memes was one thing, the furore that had grown around the allegedly sexually predatory ‘Blurred Lines’ and it’s accompanying video, starring three topless models Emily Ratajkowski, Jessi M’Bengue and Elle Evans, seemed briefly to threaten his nice guy reputation.

In an interview with Channel 4 News in May 2014, interviewer Krishnan Guru-Murthy seemed to get under his skin with his line of questioning about ‘Blurred Lines’. “Did I touch the women sexually in the video?” he responded rhetorically. “Let me ask you something, in a high fashion magazine when women have their boobs out is there something sexual there too? If you ask the director who created it – who was a woman – she was inspired by high fashion magazines where women do have their boobs out. I love women, I love them inside and out. That song was meant for women to hear and go, ‘You know, I’m a good woman and sometimes I do have bad thoughts.”

Pharrell, who at the end of last year finally married Helen Lasichanh, the mother of his son Rocket, in a ceremony in Miami, denied that his second solo album ‘G I R L’ was in any way a response to charges of chauvinism. “‘G I R L’ is the album that I’ve always dreamt of making and I was set free and reminded by the executives of Columbia when they gave me the opportunity to do the record,” he said. “They kind of just said ‘Go and make the record that you want to make and we’ll support you’. Certain people were offended by ‘Blurred Lines’, well really the video and some of the lyrics. I mean, it says ‘You don’t need no papers,’ meaning there’s no paperwork on your life and that man is not your maker. Anyway, we all come from women and that seemed like the perfect segue and the perfect way to tee up the importance of making ‘G I R L’. So, no, I had my own reasoning. I’ve always wanted to make this record, you know. I didn’t know it would be called ‘G I R L’ but I always wanted to make a record that wasn’t about me, to be honest and that’s why I’m so elated that I was able to pull it off. ‘G I R L’ is something that I needed to say for a long time.”

With ‘G I R L’ proving more successful than his first solo album or his recent N.E.R.D. records – it’s even spawned a Comme des Garçons fragrance he’s “super proud” of – Pharrell now finds himself on his biggest ever solo tour. He recently collaborated with one of his longtime heroes Spike Lee on a live web broadcast of one performance, while this September he’ll bring the tour to the UK for a date in Manchester before finishing off with two shows at London’s O2 Arena in October. For a man who started off seeing himself as a producer rather than a performer, “the man beside the man” as he often puts it, a major tour without even his N.E.R.D. bandmates is a new challenge. “I think it’s a different part of the process,” he said recently. “I think for me most of the magic is the alchemy of it all. You know, being in a studio at the moment when it’s almost done and you feel it, you see what it’s like at the end of the rainbow or whatever. When you go out to perform it you’re re-living that sort of magical moment that you felt in the studio and you’re kind of forgetting where you are. So although I’m in front of the fans and I get to hug the girls and tell them thank you so much for being so supportive, I’m also partially still back in the studio when it was all happening, in my head.”

LISTENING back to the string of hits from the last two decades that bear Pharrell’s fingerprints – from ODB and Kelis, Jay-Z and Snoop, Justin and Britney through to Daft Punk and Robin Thicke – it becomes difficult to imagine how contemporary pop would sound without him. It certainly becomes easier to see why he believes music can heal the sick. The one thing that runs through all of Pharrell’s music like a red cord is an exuberant, seductive belief that music can make us better, fitter and, in the end, well, happy. We don’t have to look to the future to experience music as medicine – we’re already dosed to the eyeballs on it.

“We know that music on a broader level can help people who would otherwise feel isolated or vulnerable and make them feel better,” says Pharrell, summing up his philosophy. “This is a thing I believe. I’m always walking around saying the same thing over and over again.”

Cover story for Loaded, September 2014.

The VICE Guide to Europe 2014

This is the VICE Guide to Europe 2014. A travel guide featuring: pork, anarchists, bicycles, politicians, fishermen, racists, tear gas, cocaine, pizzas, techno, beer, football fans, bands and waiters.

This is the VICE Guide to Europe 2014. A travel guide featuring: pork, anarchists, bicycles, politicians, fishermen, racists, tear gas, cocaine, pizzas, techno, beer, football fans, bands and waiters.

Reviewed: The UK’s Five Weirdest Euro Election Videos

Yes, the build-up to today’s European elections has been dominated entirely by a one-man publicity machine. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other groups of narcissists out there who aren’t at least as deserving of your attention. So, before you go to cast your vote for UKIP, let’s review some party political broadcasts from other groups – groups who also refuse to adhere to the staid PR conventions of Westminster’s “Big Three”, like using decent microphones and not putting giant CGI monsters in your videos.

Yes, the build-up to today’s European elections has been dominated entirely by a one-man publicity machine. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other groups of narcissists out there who aren’t at least as deserving of your attention. So, before you go to cast your vote for UKIP, let’s review some party political broadcasts from other groups – groups who also refuse to adhere to the staid PR conventions of Westminster’s “Big Three”, like using decent microphones and not putting giant CGI monsters in your videos.

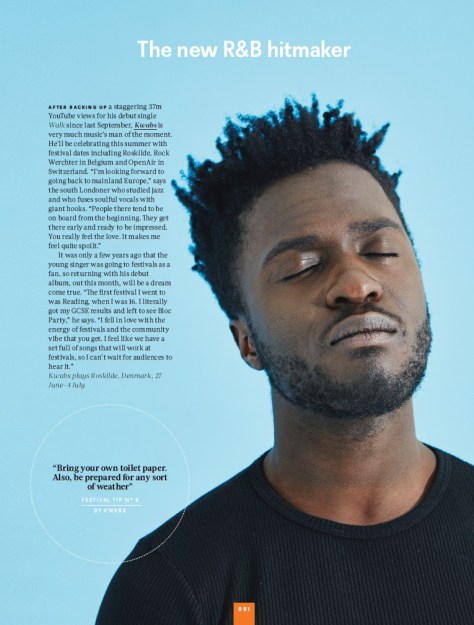

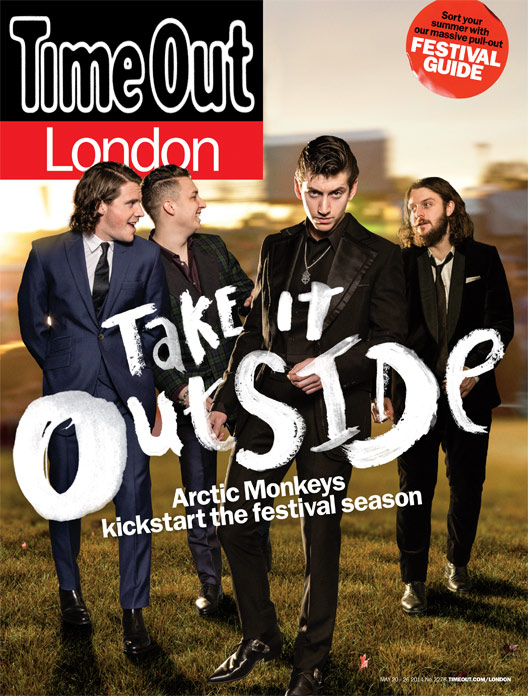

King Of The Swingers

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

Right now he’s enjoying a rare month off. After we order coffee he tells me he’s been back at his place in east London, and that he spent the previous evening dusting off his CD collection. ‘I pulled out “The Songs of Leonard Cohen” and it still had a sticker on it. £14.99!’

Money well spent, I suggest. ‘Totally,’ he agrees. ‘Fucking “Suzanne”: what a song! I don’t have an Instagram account, but if I did I’d have grammed it, saying exactly that: “Money well spent.”’

It must be nice for him to be home, enjoying the simple pleasures of rummaging through old albums? ‘I’m not even sure where home is,’ Turner sighs. ‘Probably Terminal 5. There is a strange sense of calm about arriving back at Heathrow.’

He’s spent a lot of time in the air these last eight years. The Arctic Monkeys’ record-breaking debut ‘Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not’ launched Turner, drummer Matt Helders and guitarist Jamie Cook into the stratosphere almost overnight in 2006, with fourth member Nick O’Malley joining to replace original bassist Andy Nicholson soon after. Since then the gang of schoolmates have established themselves as Britain’s biggest contemporary rock ’n’ roll band. Last year’s heavy, sultry and tremendous ‘AM’ (their fifth album) topped the charts in nine countries and set them up for a pair of huge shows in Finsbury Park this week.

Some of the fans flocking to see them will be teenagers too young to remember the band as Yorkshire urchins, trackie bottoms tucked into their socks. There are others, however, who remember it all too well: critics who’ve accused the Arctics’ frontman of now pretending to be something he’s not. At the outset Turner wrote songs about drinking and dancing and falling out of taxis, and described those nights just the way you and your mates would, if only you were blessed with a sharper turn of phrase. Now Turner spends much of the year in LA, dates a model and dresses like a screen idol – somewhere between James Dean and Marlon Brando in ‘The Wild One’. Has he been blinded by the bright lights of Stateside success? Whatever people say about Alex Turner, who is he now?

Not a man who takes himself entirely seriously, it turns out. ‘I wish I could be that guy,’ he says, when I ask him about his International Rock Star persona. He tells me he’s happiest when he’s writing, plucking new songs out of the ether. What’s the hardest part of his job? ‘Probably the same thing,’ he deadpans, in that muttering, sub-Elvis drawl he’s cultivated. He’s taking the piss out of himself. He’s too self-aware, probably too Northern, to believe his own smooth rhetoric. ‘I wish I could be the guy who says those sort of lines,’ he says. ‘I catch myself too quick.’This February, at The BRIT Awards, that self-awareness landed him in the eye of a tabloid storm. Collecting the first of the band’s two awards, for Best British Album and Best British Group, Turner made a now notorious speech about how ‘rock ’n’ roll seems like it’s faded away sometimes, but it will never die’.

He was accused of arrogance (as if that’s such a sin in a rock star) but Turner maintains that the celebration of his genre needed voicing. ‘I was trying to present an option in an entertaining way,’ he says. ‘In a room like that, where we were the only guitar band, it’s easy to start feeling like an emissary for rock ’n’ roll. If that’s what people were talking about after the Brits rather than a nipple slipping out, that’s a good thing. In a way, maybe it is a nipple slipping out.’

Raised on a diet of Britpop, Turner can’t have imagined being in Britain’s biggest rock band and having to make that sort of clarion call. I ask him if he ever feels like the Arctics are an Oasis without a Blur to lock horns with. He laughs. ‘It would be really arrogant to say that there’s just us. There are others but there are very few bands on the radio. It doesn’t have to be that way. I think that’s where that speech was coming from.’

Turner is the sort of man who chooses his words carefully, occasionally retrieving a comb from a pocket so that he can attend to his quiff and buy a few more seconds of thought. Award shows don’t come naturally. ‘As perverse as this may sound, I don’t really enjoy being the centre of attention,’ he says. ‘It’s all right during a show, because I’d argue it’s the song or the performance that’s the centre of attention. It’s not like me opening my birthday presents in front of everybody. I’m not a big fan of that. I think making a speech falls into that category. It’s like getting a trophy for a race that you didn’t really know you were running. There’s a twisted side to it. I can come off as ungrateful, but fuck it. That’s just the truth.’

That subtle sleight-of-hand to keep a part of himself out of the limelight may also explain the bequiffed, leather-clad character he’s created, although he’s quick to dismiss the idea that the band are keeping it any less ‘real’ than when they started out. ‘Tracksuits are as much of a uniform as a gold sparkly jacket,’ he says. ‘We made a decision to keep dressing like that at the start. It’s as contrived as anything else. It’s a sort of theatre.’

So don’t expect him to dig out a pair of shorts for Finsbury Park (‘Unless I’m within splashing distance of water I won’t be caught dead in them, as a rule’). He’s happy that audiences seem more excited to hear tunes from ‘AM’ than old stuff (‘Still got it!’), but he’s self-effacing about what’s made this record such a success. ‘I think the production is what makes people move. The words are just me blabbing on, the usual shit.’

Our time’s up but Turner’s in no hurry. We sit and chat about books, and as befits the sharpest lyric writer of his generation he’s the sort of reader who can quote his favourite novels. He’s a fan of Conrad and Hemingway, but above all Nabokov. He recites a line about internalised anger from ‘Despair’: ‘I continued to stir my tea long after it had done all it could with the milk.’

After an hour or so, it’s time for a smoke. As we leave the coffee shop the manager stops us. He’s noticed the turned heads. ‘Excuse me,’ he asks me, ‘are you the singer in a band?’ Alex Turner laughs out loud. He doesn’t need his ego massaging. He’s a bona fide rock ’n’ roll star.

Chuck Palahniuk: All Of Creation Just Winks Out

There’s this guy who paints houses for a living. He has a pick-up truck and a pug dog, who he loves very much. The guy has to change his health insurance so he goes for a check-up, and afterwards they ask him to come in to talk about his results with a counsellor, which is never good news. So he goes in and he’s sat across the desk from this well-dressed, middle-aged woman with a folder of results. She says: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but you’ve tested positive for HIV.”

There’s this guy who paints houses for a living. He has a pick-up truck and a pug dog, who he loves very much. The guy has to change his health insurance so he goes for a check-up, and afterwards they ask him to come in to talk about his results with a counsellor, which is never good news. So he goes in and he’s sat across the desk from this well-dressed, middle-aged woman with a folder of results. She says: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but you’ve tested positive for HIV.”

She says: “Do you know how serious this is?”

She starts to weep with the stress of having to tell him this news, but he’s lost in thought. He’s thinking how every night before he goes to sleep he jerks off into a Kleenex and drops it off the side of the bed, and every morning his dog has shredded and eaten most of it. He’s thinking that he’s killed the one thing in the world that he loves, and that loves him.

She’s going on and on about how they need to do viral load tests and what treatment might be best, and eventually he has to stop her and he says: “Can you just shut up? I’ve just got one question that I need answering.”

“I need you to tell me if I could have transmitted the AIDS virus to my pug dog?”

The woman’s face freezes into a lip-trembling mask of horror. This woman who has dedicated her life to social work and helping others. He can’t see her move but he can hear her wooden chair creaking. She’s leaning as far back as she can trying to get away from him, until it finally dawns on him and he says:

“Oh! You think I fucked my dog!”

So he tells the story about the tissues, and she is so relieved to know that she hasn’t devoted her life to counselling the sort of person who fuck pug dogs that she bursts out laughing. They’re able to laugh and to move past the impossible moment. She explains that the ‘H’ in HIV stands for ‘Human’, and they’re able to talk about what they need to talk about.

Telling that story is the reason Chuck Palahniuk isn’t allowed to speak at Barnes & Noble anymore. When he came to London, at the tail end of last year, it was one of many stories that he told onstage at Madame JoJo’s. I’d been asked to compère the night, which meant that as well as having to finally nail the pronunciation of his surname (it’s Paula-nick) I also got to sit beside Chuck and witness the effect his stories have on an audience. The way the atmosphere seemed to decompress as the audience inhaled as one and the room lost cabin pressure. Then the nervous snorts that punctuated the story and finally the lurch of redemptive laughter as we, like the man and his counsellor, moved past the impossible moment.

A few days later I met Chuck again at a genteel little guest house just off Soho Square. It was the sort of place that has oil paintings on the walls and marble busts in all the alcoves. We found a quiet place to talk in a small library with book-lined walls and a real fire burning in the hearth. In person, he speaks softly and thoughtfully. It was not the sort of atmosphere in which you would expect to be haunted by a story about fearing you’ve given your pug AIDS, yet here we were.

Chuck told me that he was sent the story, which is apparently true, by the house painter himself after he had read Palahniuk’s short story ‘Guts’. Although it was his debut 1996 novel Fight Club that made his name, ‘Guts’ burnished his reputation when ambulance-loads of people started passing out whenever he read it in public. The fact that the house painter felt comfortable sending his story to Chuck illustrates something important about his art. “It’s partly about creating the opportunity and the freedom for other people to make that same admission,” he says. “When I go up and read ‘Guts’ I humiliate and debase myself in a public way. It gives the audience this superiority that gives them the freedom to risk that kind of debasement in order to admit something about themselves.”

You can read ‘Guts’ in full here, and I urge you to do so if you haven’t. Hurry back, I’ll hold my breath. The first time I ever read that story, I was talking to a good-looking girl at a party about how much Fight Club had blown apart my young world and she told me I had to read this short story by the same writer. In fact, she said, I should read it aloud to the whole party. This is a good example of why you shouldn’t try to impress good-looking girls at parties. Chuck gets a hoot out of this when I tell him. “You had no idea where it was going?” he asks. “What a laugh that was.”

For those who need reminding, it’s a series of three escalating stories about the things that young men will do to make stroking their own penises feel more intense, each with more horrendous consequences than the last. To make matters even worse, Chuck says that like the pug dog tale each of these stories are essentially true.

“I’d been carrying around two parts of ‘Guts’ since my college days,” he says. He knitted them together, tinkering with details – like standardising all their ages to 13 – but the stories themselves were obtained with good old-fashioned journalistic initiative. “The carrot story took a lot of drinking. I had to get my friend so drunk. The candle story came from another friend who had been in the military and had been discharged and now was going to college. He phoned me and asked me to pick up all of his homework for several classes. It took a lot of over-the-phone manipulation. I eventually said: ‘I will not pick up your homework until you tell me what happened’. I had to threaten him to get that story.”

So Chuck carried those two stories around with him, looking for a third to complete the set. “I knew I needed a third act, and I needed a bridge verse as well. I thought of it like a song, with three verses and a bridge. For the bridge verse, I used that passage about how most of the last peak of teen suicide was really kids choking to death. I love to read forensic science textbooks. I started to notice that medical examiner procedural textbooks started to include a new chapter in the 1990s about how to identify auto-erotic asphyxiations where the crime scene has been manipulated by loving friends and family. I wanted to include that information as a sort of big voice observation, before we land in the ultimate anecdote. That’s how the story went together: like a song, with three verses and a bridge.”

He found his third verse when he was hanging out at a sexual compulsive support group, doing research for his 2001 novel Choke. “I asked this very thin man how he stayed in such good shape, and he explained that he couldn’t eat meat. I asked why, if it was an allergy, and he said no, he just had a reduced large intestine. It took a lot of talking before he eventually told me that he’d had a radical bowel resectioning, and why. I kind of embroidered it a little. There’s no way you could survive losing that much intestine. He did not bite through it, but he did have a prolapsed bowel from doing that and he did have to somehow wrench it out of the machinery to save his life. He told me the whole thing face-to-face, but it was a very gentle unpacking.”

At Madame JoJo’s, Chuck read a new short story, ‘Zombie’, which you can read in full here. Again, speaking as someone with your best interests at heart I advise you to go and do so immediately. Chuck thinks it’s a new standard bearer for his work: “It’s nice, every few years, to bring out something that’s really strong, that becomes the signature scandalous thing. For so long it was Fight Club. Then it became something else. Then ‘Guts’ carried the weight for a long time. I think this year’s story, ‘Zombie’, will be another perennial story.”

What floored me when I heard Chuck read ‘Zombie’ was the fact that while it starts out with typically Palahniukian helpings of dark humour, cynicism and nihilism, ultimately the story rejects those ideas in favour of an essential optimism: the existential meaning that can be provided by our sense of community.

“For me, it’s a big breakthrough,” he agrees. “I see my generation as snarky because it was our default identity in the face of the earnestness of the hippies at Woodstock. All of that was a sincere attempt to save the world. Our reaction to that was punk and new wave and with them cynicism, irony and sarcasm. We needed to be to be the reverse of the preceding generation. I want another option. I’m not going to live forever, so why not risk the ultimate transgression for my generation: to be sentimental and to be vulnerable. I think the breakthrough in the story is where the character says: “I don’t even know what a happy ending is.” I think my generation doesn’t believe in happy endings. The first step to resolving that is to admit that we have no idea what a happy ending would be anymore. By making the admission, we’re opening the vulnerability to maybe make it happen.”

Admitting we don’t know what a happy ending looks like, now that our old belief systems are gone, is the first step to finding one. ‘Zombie’ seems to echo that old Gramsci line: “The challenge of modernity is to live without illusions without becoming disillusioned.”

Likewise, Fight Club was about finding a device, almost a game, by which to deal with existential angst. It’s about bravery in the face of the void, as Philip Larkin wrote in ‘Aubade’: “Courage is no good, it means not scaring others. Being brave lets no one off the grave.”

“Beyond just being stoic about it, I liked the idea of being playful about it,” says Chuck. “I think so many discoveries come through the joy of play. Fight Club was about finding a game that would allow the impossible thing to be explored. I was so confronted by violence that I thought if there was a consensual, structured way that I could explore violence, experience violence, inflict violence, then I could develop a greater understanding and mastery and I wouldn’t have that fear. Fear of death is why I started going to those terminal illness support groups and volunteering in hospices, so that I would see at least what the physical process was and how other people dealt with it. As a young adult in my mid-twenties I would at least be taking some action, and have some experience of the thing, so that it wouldn’t be preying on me all the time. It looks like such an impossible thing to die. I think I wrote that into the character of Madison when I wrote Doomed. When she looks at her Grandmother’s hand she sees age spots and wrinkles and thinks: ‘How am I ever going to accomplish that?’ I look at my own hands now and see liver spots that my grandmother had. I remember being a child and thinking ‘Wow! How did those happen?’ It seems so miraculous to find them on my own hand now.”

We’ve reached a terminal point, so let’s go back to the beginning.

Chuck Palahniuk was born on 21 February 1962 in a city called Pasco in Washington State. His family history is bloodier than fiction. His grandfather killed his grandmother, and then himself. Chuck’s father, who was three years old, was at home at the time. “His earliest memories were of being in the house and hiding while his father was trying to find him and kill him.”

Chuck’s father worked on the railroad, an itinerant lifestyle which he and his brother swore they’d never repeat. Now his brother works in Angola, with a family in South Africa, while Chuck spends a third of his time on the road. “We’ve both ended up with my father’s life,” he says with a wry smile.

He says he didn’t learn how to read or write until he was eight or nine, in the third grade. “I think I was the last child in my class. I was filled with terror that I was going to be left behind. When I finally was able to read and write I was filled with such joy that I think that’s why I attached so much to it.”

Chuck talks passionately about how raising a child helps you to understand your own upbringing and to question all your assumptions about the world. “A child is a constantly quizzing thing,” he says. However, he’s talking about the experiences of his friends. Chuck is gay, a subject he doesn’t usually talk about in interviews, but in the context of raising a child I ask whether he’s considered surrogacy or adoption.

“No!” he says immediately. “I devour biographies and writers make really terrible parents. Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, William Burroughs – oh my God! They were all self-involved and self-obsessed and all of their children suffered.”

Does he recognise that in himself?

“Yeah, I’m completely selfish. I’m just glad that my partner is really good at letting me be obsessed with what I’m obsessed about. I’m really blessed. We’ve been together for twenty years, since before I started to write, so he’s kind of seen me through one persona into a completely different persona. When we met I was working at Freightliner, he was working stocking aircraft for an airline. We both had these very blue-collar lives, and now our lives are completely different.”

Chuck was in his thirties before he started attending creative writing workshops. He learned to write standing on a bar. His teacher, Tom Spanbauer, would arrange public readings in sports bars. “People were involved in sports on televisions or playing pool or pinball or videogames,” says Chuck. “I remember seeing friends of mine trying to read heartfelt memoir that was so subtle and emotionally sensitive that they would be weeping and no-one would give a shit. When it came my turn to stand on the bar and read I made sure that the thing that I read drew the attention of the entire bar, and it worked.”

In Spanbauer’s workshops he studied short-story writers like Mark Richard and his “extraordinary” collection The Ice At The Bottom Of The World, Thom Jones’ “amazing” The Pugilist At Rest and Denis Johnson’s collection Jesus’ Son. Chuck also adored Kurt Vonnegut, and learned from his work the beauty of the repeated chorus, as in Slaughterhouse Five‘s ‘So it goes’. Palahniuk loves them because of “that wonderful way that they keep the past always present, and they provide a standard transition that allows you to move past the impossible moment. I love those cultural ways which we have of getting past that moment where nothing can be said.”

His writing routine is still informed by his early experiences of reading stories aloud in a noisy bar, and he’s wary of the internet, a place where stories grow stale. “I almost never go to the internet for anything, except for maybe to check the spelling of a name, because if it’s on the internet then it’s not fresh. It’s not something original. It really takes talking to people to draw out these fantastic, unrealised new things. I write longhand. I tend to do what they used to call brain-mapping, where you have an idea and you gather everything you can in relation to that idea. I’ll compile notebooks full of handwritten notes exploring every facet of the thing I want to ultimately write about. Then at some point it will start to crystallise and I’ll sit down at a keyboard. When I talk about writing Fight Club in six weeks, or next year’s novel Beautiful You which I wrote in six weeks, I’m really talking about the keyboarding part. The writing took a year or more, but the keyboarding took six weeks.”

Chuck’s way of dealing with the writer’s terror of the blank page is to physically put himself in the places where stories happen. “I want to be in the world,” he says. “I want to be interacting with people and I want to produce something that can compete with the real world. I want to write in largely the same circumstances in which my work will be consumed, in places like bars or airports or hospitals, where people are surrounded by stress and distraction. If I can produce the work in those circumstances I think it’s more likely that people can consume the work there.”

He says the best piece of advice he’s received about writing was from Joy Williams’ essay ‘Uncanny Singing That Comes from Certain Husks’, where she writes: “A writer isn’t supposed to make friends.” Chuck grins as he recites those words. “I just so love that. The idea that you don’t write something in order to be liked. It transcends that. That has nothing to do with genuine writing. It moves me to think about that. “You don’t write to make friends.””

Just as you don’t write to make friends, he argues that when he’s first pitching a story to an editor, it’s less important that they like it and more important that they simply can’t forget it. “Eventually they will recognise some value in it,” he explains. “I think my short stories especially have a depth to them that very few people get. Very few people recognise the fantastic sadness at the end of ‘Guts’. I’m glad that they don’t. It’s nice that they come out of it with a lot of laughs, but occasionally I get a letter from someone saying that when the father has reduced his son to the idiot family dog, that’s heartbreaking, that’s the saddest thing I’ve ever read, and the fact that somebody recognises that makes it all worthwhile. Even if just one person gets it. It’s so gratifying.”

Iris Murdoch said that “every book is the wreck of a perfect idea,” and I want to know whether Chuck still struggles with sealing an unforgettable idea or an ear-catching bar tale in the wax of prose. He says: “That’s the way it used to be. I used to be in love with the idea but now I realise that what I’m in love with is just the tiniest seed of the idea. The idea is going to grow and evolve and bring me to something I could never comprehend in the first place. I can’t be the person who came up with the idea and be the person who has the answer at the end. I’m going to have to grow and evolve through the whole process as well. So I accept that struggle, and that there are going to be unpleasant parts in that struggle where I’m just stymied, but that eventually we all work through those. It’s like my Eiffel Tower story… do you mind if I tell that?”

Not at all.

“Years ago I was in Paris and my publisher threw me this dinner party. Everyone at this party was smoking. I had arrived the day before, so I was jetlagged, and my schedule was just dense with obligations. I was so tired and I knew the day after and the day after and the day after were going to be an ordeal. The last thing I wanted to do was stay up late at this dinner party listening to people speak French, which I don’t speak, and breathing their cigarette smoke. I was so angry because they were just ignoring me. They were talking about whatever they were talking about and it was getting later and later, so I finally begged a couple, who were very drunk, to take me back to my hotel. They were so drunk that they would get lost. They would sit through green lights and run red lights. I was terrified that I would be killed in a car accident. We seemed to be aimlessly driving through Paris, in one direction and then back in the same direction. Just criss-crossing Paris aimlessly. Finally, they pulled up on a kerb near the Eiffel Tower. They parked on the kerb, they left the engine running, they threw the doors open, they jumped out and then screamed: “Chuck, run!” They abandoned the car and started running across the plaza towards the Eiffel Tower. These policemen started to approach us, and I didn’t know what to do so I chased after them. I was just running. They were screaming back at me: “Run, run, we’ve got to run!” I thought maybe they had drugs, and we were about to be arrested for possession. The police were chasing us. As we got underneath the Eiffel Tower they stopped and started screaming: “Look up! Look up!” The Eiffel Tower was all lit up. It was blazing with lights. When you’re under the centre – I didn’t know this – and you look up, it’s this tapering, blazingly bright tunnel that flares in on all sides. We were standing under the very centre looking up at this tunnel that seems to stretch into infinity. As I’m looking up into this tunnel, out of breath and drenched in sweat, my heart is pounding… everything vanishes. All of creation just winks out. There is nothing. Not a sound. Not a light. All I can hear is this collective gasp of breath. The few people who were there at that moment all inhaled at the same moment. I became disorientated in this total darkness and my knees buckled. I had to grasp the pavement because I had such vertigo in that moment of complete nothingness.”

“It turned out that for the whole dinner party what they had been debating was what experience I had to have while I was in Paris? What was the most striking thing that they had to show me? They all decided that I needed to be underneath the Eiffel Tower at midnight when they shut off the lights. They flip all the lights off with a single switch and the whole thing goes to darkness. The entire evening, including the meander through Paris, had been a delaying tactic, so that I would arrive out-of-breath underneath the centre of the Eiffel Tower at exactly the right moment. The whole thing had been a conspiracy to bring me to an ecstasy that I couldn’t conceive of. I had been so filled with rage, and so sure that they hated me and I hated them, and this was such a reversal that it really was an ecstasy. It was a weeping euphoria. Since then it has changed how I feel about writing. That it may be gruesome and torturous in this moment, but the next moment might be an ecstasy greater than anything I could have imagined. The book might not be exactly that seed that you fell in love with, but what it ends up as might be something so beyond who you were when you came up with that idea that it might be this deliverance to something extraordinary. It’s changed how I feel about life too. Maybe life itself, with all of its moments of irritation and suffering might be a conspiracy to bring us to an ecstasy that now we can’t even conceive of.”

Chet Faker

Who knew an earworm could change your life? Three years ago, Nick Murphy stumbled home from DJing in a bar and sat down in front of Ableton to make a beat. “I’d obviously had too much to drink,” he grins. “When I was writing it I thought it was going to be an original, but I had ‘No Diggity’ in my head. I totally get the words wrong. Nobody’s pulled me up on that yet…”

The next day he stuck his reworked, and reworded, cover on YouTube for his friends to hear. Within two months it was the top track on Hype Machine. Emails and offers started to flood in, which meant he could focus on music – although his day job at a bookshop had been pretty good for a voracious reader. “I just read all day and spoke to weirdos,” he says. “You should have seen the place, it was like ‘Black Books’.”

He’s spent the last two years writing “about 80” tracks, culled to 12 for debut record ‘Built On Glass’. He adheres to Hemingway’s maxim that you have to write ninety-one pages of shit to get one page of masterpiece. “That’s it,” he laughs. “I got plenty of shit.”

‘Built On Glass’ is his own chance to write something that connects with people. “The big lesson is that no-one gives a shit,” he says. “but if you write a song that’s good enough people are happy to listen to your problems. It’s no longer whining, it’s art!”

Originally published in Mixmag, May 2014.

Campaigning In A Galaxy Far, Far Away…

When was the last time you went online? Within the last hour? The last five minutes? Are you, in fact, checking your emails on your phone with one hand while you flip through this magazine? Are you half-wondering what you might tweet about it?

When was the last time you went online? Within the last hour? The last five minutes? Are you, in fact, checking your emails on your phone with one hand while you flip through this magazine? Are you half-wondering what you might tweet about it?

In 2014, the internet is where most of us live. That goes for the whole planet. Once in a small café in Koraput, a rural town in Orissa, in the east of India, a teenage boy asked me ‘what’s your name?’ Within moments he was showing me my own Facebook profile on his smartphone screen. That’s in a place that never got landlines.

When we lived in towns, we marched on the streets to get our voices heard. Now it’s easier than ever to mobilise mass protests online, particularly thanks to campaigning sites like Avaaz and Upworthy, but it’s also easier than ever for those in power to ignore them.

Drug Traffickers Build the Best Theme Parks

When Colombian National Police finally put a bullet through Pablo Escobar’s head in December 1993, he was running what was probably the most successful cocaine cartel of all time, worth some $25 billion (£15 billion). You can do pretty much anything you want with that kind of money, and Escobar did, building houses for the poor, getting himself elected to Colombia’s Congress and running much of the northeastern city of Medellín as his own personal fiefdom.

When Colombian National Police finally put a bullet through Pablo Escobar’s head in December 1993, he was running what was probably the most successful cocaine cartel of all time, worth some $25 billion (£15 billion). You can do pretty much anything you want with that kind of money, and Escobar did, building houses for the poor, getting himself elected to Colombia’s Congress and running much of the northeastern city of Medellín as his own personal fiefdom.

In 1978 he bought up a vast tract of land outside the city and set about building Hacienda Nápoles, the sort of sprawling complex that you’d expect the world’s richest drug dealer to inhabit, complete with its own array of wild animals. When he died, the land was ignored for a decade and fell into disrepair. The house was looted by locals who were convinced he’d stashed money or drugs in the walls, and the hippos turned feral.

Eventually, some bright spark hit upon the idea of reopening the estate as an adventure park. They kept the name, gave it a Jurassic Park-style makeover and reopened it to the public, creating the ultimate family-friendly tourist destination: a still pretty run-down complex with some dinosaur figurines, some hippos and the enduring, unavoidable legacy of a man whose cartel were responsible for anywhere between 3,000 to 60,000 deaths.

Eventually, some bright spark hit upon the idea of reopening the estate as an adventure park. They kept the name, gave it a Jurassic Park-style makeover and reopened it to the public, creating the ultimate family-friendly tourist destination: a still pretty run-down complex with some dinosaur figurines, some hippos and the enduring, unavoidable legacy of a man whose cartel were responsible for anywhere between 3,000 to 60,000 deaths.

Route 94

Barely out of his teens, Rowan Jones is already an old pro. Having first started making beats on a downloaded demo of FruityLoops at just 13, by 17 he was playing dubstep as Dream at places like Cable, Ministry of Sound and Fabric.

“I’ve been DJing in clubs since before I was old enough to be in clubs,” he admits. “I’ve never been out as a punter. I was either making tunes or I was locked in the green room, doing things I shouldn’t be doing.”

At the grand old age of 18 he realised he’d “kind of hit a wall”. Route 94 was born when he sent ‘Window’, a house track he’d been working on, to New York Transit Authority. “I didn’t think much of it,” he says. “But then he put it in a FACT mix. People started going mad for it and it dawned on me: ‘Shit, I’m actually quite good at this’.”

The deep house of ‘My Love’ shows the direction he’s heading under the tutelage of new manager Artwork. “Because I’m so young having people like him and Skream around is amazing,” he says. “I can take a leaf out of their books.”