There’s this guy who paints houses for a living. He has a pick-up truck and a pug dog, who he loves very much. The guy has to change his health insurance so he goes for a check-up, and afterwards they ask him to come in to talk about his results with a counsellor, which is never good news. So he goes in and he’s sat across the desk from this well-dressed, middle-aged woman with a folder of results. She says: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but you’ve tested positive for HIV.”

There’s this guy who paints houses for a living. He has a pick-up truck and a pug dog, who he loves very much. The guy has to change his health insurance so he goes for a check-up, and afterwards they ask him to come in to talk about his results with a counsellor, which is never good news. So he goes in and he’s sat across the desk from this well-dressed, middle-aged woman with a folder of results. She says: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but you’ve tested positive for HIV.”

She says: “Do you know how serious this is?”

She starts to weep with the stress of having to tell him this news, but he’s lost in thought. He’s thinking how every night before he goes to sleep he jerks off into a Kleenex and drops it off the side of the bed, and every morning his dog has shredded and eaten most of it. He’s thinking that he’s killed the one thing in the world that he loves, and that loves him.

She’s going on and on about how they need to do viral load tests and what treatment might be best, and eventually he has to stop her and he says: “Can you just shut up? I’ve just got one question that I need answering.”

“I need you to tell me if I could have transmitted the AIDS virus to my pug dog?”

The woman’s face freezes into a lip-trembling mask of horror. This woman who has dedicated her life to social work and helping others. He can’t see her move but he can hear her wooden chair creaking. She’s leaning as far back as she can trying to get away from him, until it finally dawns on him and he says:

“Oh! You think I fucked my dog!”

So he tells the story about the tissues, and she is so relieved to know that she hasn’t devoted her life to counselling the sort of person who fuck pug dogs that she bursts out laughing. They’re able to laugh and to move past the impossible moment. She explains that the ‘H’ in HIV stands for ‘Human’, and they’re able to talk about what they need to talk about.

Telling that story is the reason Chuck Palahniuk isn’t allowed to speak at Barnes & Noble anymore. When he came to London, at the tail end of last year, it was one of many stories that he told onstage at Madame JoJo’s. I’d been asked to compère the night, which meant that as well as having to finally nail the pronunciation of his surname (it’s Paula-nick) I also got to sit beside Chuck and witness the effect his stories have on an audience. The way the atmosphere seemed to decompress as the audience inhaled as one and the room lost cabin pressure. Then the nervous snorts that punctuated the story and finally the lurch of redemptive laughter as we, like the man and his counsellor, moved past the impossible moment.

A few days later I met Chuck again at a genteel little guest house just off Soho Square. It was the sort of place that has oil paintings on the walls and marble busts in all the alcoves. We found a quiet place to talk in a small library with book-lined walls and a real fire burning in the hearth. In person, he speaks softly and thoughtfully. It was not the sort of atmosphere in which you would expect to be haunted by a story about fearing you’ve given your pug AIDS, yet here we were.

Chuck told me that he was sent the story, which is apparently true, by the house painter himself after he had read Palahniuk’s short story ‘Guts’. Although it was his debut 1996 novel Fight Club that made his name, ‘Guts’ burnished his reputation when ambulance-loads of people started passing out whenever he read it in public. The fact that the house painter felt comfortable sending his story to Chuck illustrates something important about his art. “It’s partly about creating the opportunity and the freedom for other people to make that same admission,” he says. “When I go up and read ‘Guts’ I humiliate and debase myself in a public way. It gives the audience this superiority that gives them the freedom to risk that kind of debasement in order to admit something about themselves.”

You can read ‘Guts’ in full here, and I urge you to do so if you haven’t. Hurry back, I’ll hold my breath. The first time I ever read that story, I was talking to a good-looking girl at a party about how much Fight Club had blown apart my young world and she told me I had to read this short story by the same writer. In fact, she said, I should read it aloud to the whole party. This is a good example of why you shouldn’t try to impress good-looking girls at parties. Chuck gets a hoot out of this when I tell him. “You had no idea where it was going?” he asks. “What a laugh that was.”

For those who need reminding, it’s a series of three escalating stories about the things that young men will do to make stroking their own penises feel more intense, each with more horrendous consequences than the last. To make matters even worse, Chuck says that like the pug dog tale each of these stories are essentially true.

“I’d been carrying around two parts of ‘Guts’ since my college days,” he says. He knitted them together, tinkering with details – like standardising all their ages to 13 – but the stories themselves were obtained with good old-fashioned journalistic initiative. “The carrot story took a lot of drinking. I had to get my friend so drunk. The candle story came from another friend who had been in the military and had been discharged and now was going to college. He phoned me and asked me to pick up all of his homework for several classes. It took a lot of over-the-phone manipulation. I eventually said: ‘I will not pick up your homework until you tell me what happened’. I had to threaten him to get that story.”

So Chuck carried those two stories around with him, looking for a third to complete the set. “I knew I needed a third act, and I needed a bridge verse as well. I thought of it like a song, with three verses and a bridge. For the bridge verse, I used that passage about how most of the last peak of teen suicide was really kids choking to death. I love to read forensic science textbooks. I started to notice that medical examiner procedural textbooks started to include a new chapter in the 1990s about how to identify auto-erotic asphyxiations where the crime scene has been manipulated by loving friends and family. I wanted to include that information as a sort of big voice observation, before we land in the ultimate anecdote. That’s how the story went together: like a song, with three verses and a bridge.”

He found his third verse when he was hanging out at a sexual compulsive support group, doing research for his 2001 novel Choke. “I asked this very thin man how he stayed in such good shape, and he explained that he couldn’t eat meat. I asked why, if it was an allergy, and he said no, he just had a reduced large intestine. It took a lot of talking before he eventually told me that he’d had a radical bowel resectioning, and why. I kind of embroidered it a little. There’s no way you could survive losing that much intestine. He did not bite through it, but he did have a prolapsed bowel from doing that and he did have to somehow wrench it out of the machinery to save his life. He told me the whole thing face-to-face, but it was a very gentle unpacking.”

At Madame JoJo’s, Chuck read a new short story, ‘Zombie’, which you can read in full here. Again, speaking as someone with your best interests at heart I advise you to go and do so immediately. Chuck thinks it’s a new standard bearer for his work: “It’s nice, every few years, to bring out something that’s really strong, that becomes the signature scandalous thing. For so long it was Fight Club. Then it became something else. Then ‘Guts’ carried the weight for a long time. I think this year’s story, ‘Zombie’, will be another perennial story.”

What floored me when I heard Chuck read ‘Zombie’ was the fact that while it starts out with typically Palahniukian helpings of dark humour, cynicism and nihilism, ultimately the story rejects those ideas in favour of an essential optimism: the existential meaning that can be provided by our sense of community.

“For me, it’s a big breakthrough,” he agrees. “I see my generation as snarky because it was our default identity in the face of the earnestness of the hippies at Woodstock. All of that was a sincere attempt to save the world. Our reaction to that was punk and new wave and with them cynicism, irony and sarcasm. We needed to be to be the reverse of the preceding generation. I want another option. I’m not going to live forever, so why not risk the ultimate transgression for my generation: to be sentimental and to be vulnerable. I think the breakthrough in the story is where the character says: “I don’t even know what a happy ending is.” I think my generation doesn’t believe in happy endings. The first step to resolving that is to admit that we have no idea what a happy ending would be anymore. By making the admission, we’re opening the vulnerability to maybe make it happen.”

Admitting we don’t know what a happy ending looks like, now that our old belief systems are gone, is the first step to finding one. ‘Zombie’ seems to echo that old Gramsci line: “The challenge of modernity is to live without illusions without becoming disillusioned.”

Likewise, Fight Club was about finding a device, almost a game, by which to deal with existential angst. It’s about bravery in the face of the void, as Philip Larkin wrote in ‘Aubade’: “Courage is no good, it means not scaring others. Being brave lets no one off the grave.”

“Beyond just being stoic about it, I liked the idea of being playful about it,” says Chuck. “I think so many discoveries come through the joy of play. Fight Club was about finding a game that would allow the impossible thing to be explored. I was so confronted by violence that I thought if there was a consensual, structured way that I could explore violence, experience violence, inflict violence, then I could develop a greater understanding and mastery and I wouldn’t have that fear. Fear of death is why I started going to those terminal illness support groups and volunteering in hospices, so that I would see at least what the physical process was and how other people dealt with it. As a young adult in my mid-twenties I would at least be taking some action, and have some experience of the thing, so that it wouldn’t be preying on me all the time. It looks like such an impossible thing to die. I think I wrote that into the character of Madison when I wrote Doomed. When she looks at her Grandmother’s hand she sees age spots and wrinkles and thinks: ‘How am I ever going to accomplish that?’ I look at my own hands now and see liver spots that my grandmother had. I remember being a child and thinking ‘Wow! How did those happen?’ It seems so miraculous to find them on my own hand now.”

We’ve reached a terminal point, so let’s go back to the beginning.

Chuck Palahniuk was born on 21 February 1962 in a city called Pasco in Washington State. His family history is bloodier than fiction. His grandfather killed his grandmother, and then himself. Chuck’s father, who was three years old, was at home at the time. “His earliest memories were of being in the house and hiding while his father was trying to find him and kill him.”

Chuck’s father worked on the railroad, an itinerant lifestyle which he and his brother swore they’d never repeat. Now his brother works in Angola, with a family in South Africa, while Chuck spends a third of his time on the road. “We’ve both ended up with my father’s life,” he says with a wry smile.

He says he didn’t learn how to read or write until he was eight or nine, in the third grade. “I think I was the last child in my class. I was filled with terror that I was going to be left behind. When I finally was able to read and write I was filled with such joy that I think that’s why I attached so much to it.”

Chuck talks passionately about how raising a child helps you to understand your own upbringing and to question all your assumptions about the world. “A child is a constantly quizzing thing,” he says. However, he’s talking about the experiences of his friends. Chuck is gay, a subject he doesn’t usually talk about in interviews, but in the context of raising a child I ask whether he’s considered surrogacy or adoption.

“No!” he says immediately. “I devour biographies and writers make really terrible parents. Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, William Burroughs – oh my God! They were all self-involved and self-obsessed and all of their children suffered.”

Does he recognise that in himself?

“Yeah, I’m completely selfish. I’m just glad that my partner is really good at letting me be obsessed with what I’m obsessed about. I’m really blessed. We’ve been together for twenty years, since before I started to write, so he’s kind of seen me through one persona into a completely different persona. When we met I was working at Freightliner, he was working stocking aircraft for an airline. We both had these very blue-collar lives, and now our lives are completely different.”

Chuck was in his thirties before he started attending creative writing workshops. He learned to write standing on a bar. His teacher, Tom Spanbauer, would arrange public readings in sports bars. “People were involved in sports on televisions or playing pool or pinball or videogames,” says Chuck. “I remember seeing friends of mine trying to read heartfelt memoir that was so subtle and emotionally sensitive that they would be weeping and no-one would give a shit. When it came my turn to stand on the bar and read I made sure that the thing that I read drew the attention of the entire bar, and it worked.”

In Spanbauer’s workshops he studied short-story writers like Mark Richard and his “extraordinary” collection The Ice At The Bottom Of The World, Thom Jones’ “amazing” The Pugilist At Rest and Denis Johnson’s collection Jesus’ Son. Chuck also adored Kurt Vonnegut, and learned from his work the beauty of the repeated chorus, as in Slaughterhouse Five‘s ‘So it goes’. Palahniuk loves them because of “that wonderful way that they keep the past always present, and they provide a standard transition that allows you to move past the impossible moment. I love those cultural ways which we have of getting past that moment where nothing can be said.”

His writing routine is still informed by his early experiences of reading stories aloud in a noisy bar, and he’s wary of the internet, a place where stories grow stale. “I almost never go to the internet for anything, except for maybe to check the spelling of a name, because if it’s on the internet then it’s not fresh. It’s not something original. It really takes talking to people to draw out these fantastic, unrealised new things. I write longhand. I tend to do what they used to call brain-mapping, where you have an idea and you gather everything you can in relation to that idea. I’ll compile notebooks full of handwritten notes exploring every facet of the thing I want to ultimately write about. Then at some point it will start to crystallise and I’ll sit down at a keyboard. When I talk about writing Fight Club in six weeks, or next year’s novel Beautiful You which I wrote in six weeks, I’m really talking about the keyboarding part. The writing took a year or more, but the keyboarding took six weeks.”

Chuck’s way of dealing with the writer’s terror of the blank page is to physically put himself in the places where stories happen. “I want to be in the world,” he says. “I want to be interacting with people and I want to produce something that can compete with the real world. I want to write in largely the same circumstances in which my work will be consumed, in places like bars or airports or hospitals, where people are surrounded by stress and distraction. If I can produce the work in those circumstances I think it’s more likely that people can consume the work there.”

He says the best piece of advice he’s received about writing was from Joy Williams’ essay ‘Uncanny Singing That Comes from Certain Husks’, where she writes: “A writer isn’t supposed to make friends.” Chuck grins as he recites those words. “I just so love that. The idea that you don’t write something in order to be liked. It transcends that. That has nothing to do with genuine writing. It moves me to think about that. “You don’t write to make friends.””

Just as you don’t write to make friends, he argues that when he’s first pitching a story to an editor, it’s less important that they like it and more important that they simply can’t forget it. “Eventually they will recognise some value in it,” he explains. “I think my short stories especially have a depth to them that very few people get. Very few people recognise the fantastic sadness at the end of ‘Guts’. I’m glad that they don’t. It’s nice that they come out of it with a lot of laughs, but occasionally I get a letter from someone saying that when the father has reduced his son to the idiot family dog, that’s heartbreaking, that’s the saddest thing I’ve ever read, and the fact that somebody recognises that makes it all worthwhile. Even if just one person gets it. It’s so gratifying.”

Iris Murdoch said that “every book is the wreck of a perfect idea,” and I want to know whether Chuck still struggles with sealing an unforgettable idea or an ear-catching bar tale in the wax of prose. He says: “That’s the way it used to be. I used to be in love with the idea but now I realise that what I’m in love with is just the tiniest seed of the idea. The idea is going to grow and evolve and bring me to something I could never comprehend in the first place. I can’t be the person who came up with the idea and be the person who has the answer at the end. I’m going to have to grow and evolve through the whole process as well. So I accept that struggle, and that there are going to be unpleasant parts in that struggle where I’m just stymied, but that eventually we all work through those. It’s like my Eiffel Tower story… do you mind if I tell that?”

Not at all.

“Years ago I was in Paris and my publisher threw me this dinner party. Everyone at this party was smoking. I had arrived the day before, so I was jetlagged, and my schedule was just dense with obligations. I was so tired and I knew the day after and the day after and the day after were going to be an ordeal. The last thing I wanted to do was stay up late at this dinner party listening to people speak French, which I don’t speak, and breathing their cigarette smoke. I was so angry because they were just ignoring me. They were talking about whatever they were talking about and it was getting later and later, so I finally begged a couple, who were very drunk, to take me back to my hotel. They were so drunk that they would get lost. They would sit through green lights and run red lights. I was terrified that I would be killed in a car accident. We seemed to be aimlessly driving through Paris, in one direction and then back in the same direction. Just criss-crossing Paris aimlessly. Finally, they pulled up on a kerb near the Eiffel Tower. They parked on the kerb, they left the engine running, they threw the doors open, they jumped out and then screamed: “Chuck, run!” They abandoned the car and started running across the plaza towards the Eiffel Tower. These policemen started to approach us, and I didn’t know what to do so I chased after them. I was just running. They were screaming back at me: “Run, run, we’ve got to run!” I thought maybe they had drugs, and we were about to be arrested for possession. The police were chasing us. As we got underneath the Eiffel Tower they stopped and started screaming: “Look up! Look up!” The Eiffel Tower was all lit up. It was blazing with lights. When you’re under the centre – I didn’t know this – and you look up, it’s this tapering, blazingly bright tunnel that flares in on all sides. We were standing under the very centre looking up at this tunnel that seems to stretch into infinity. As I’m looking up into this tunnel, out of breath and drenched in sweat, my heart is pounding… everything vanishes. All of creation just winks out. There is nothing. Not a sound. Not a light. All I can hear is this collective gasp of breath. The few people who were there at that moment all inhaled at the same moment. I became disorientated in this total darkness and my knees buckled. I had to grasp the pavement because I had such vertigo in that moment of complete nothingness.”

“It turned out that for the whole dinner party what they had been debating was what experience I had to have while I was in Paris? What was the most striking thing that they had to show me? They all decided that I needed to be underneath the Eiffel Tower at midnight when they shut off the lights. They flip all the lights off with a single switch and the whole thing goes to darkness. The entire evening, including the meander through Paris, had been a delaying tactic, so that I would arrive out-of-breath underneath the centre of the Eiffel Tower at exactly the right moment. The whole thing had been a conspiracy to bring me to an ecstasy that I couldn’t conceive of. I had been so filled with rage, and so sure that they hated me and I hated them, and this was such a reversal that it really was an ecstasy. It was a weeping euphoria. Since then it has changed how I feel about writing. That it may be gruesome and torturous in this moment, but the next moment might be an ecstasy greater than anything I could have imagined. The book might not be exactly that seed that you fell in love with, but what it ends up as might be something so beyond who you were when you came up with that idea that it might be this deliverance to something extraordinary. It’s changed how I feel about life too. Maybe life itself, with all of its moments of irritation and suffering might be a conspiracy to bring us to an ecstasy that now we can’t even conceive of.”

Originally published by The Quietus.

Scandinavians speak perfect English, they’re blessed with Viking genetics and if their wide-ranging musical output is any kind of yardstick they’re into everything from Abba to black metal. This should make them the world’s best festival hosts. Sadly they live in a place where it’s reasonable to charge £8 for a beer. It’s a steep price to pay, but if you’re willing then Norway’s Øya is ready to welcome you with open arms and a four-day line-up to rival anywhere on the planet.

Scandinavians speak perfect English, they’re blessed with Viking genetics and if their wide-ranging musical output is any kind of yardstick they’re into everything from Abba to black metal. This should make them the world’s best festival hosts. Sadly they live in a place where it’s reasonable to charge £8 for a beer. It’s a steep price to pay, but if you’re willing then Norway’s Øya is ready to welcome you with open arms and a four-day line-up to rival anywhere on the planet.

At first, Yung Lean’s Yoshi City video is just like any other young up-and-coming rapper’s. The teenager hangs out of a moving car surrounded by his crew. There’s a phone in his hand, a fag in his mouth. But the familiar rap tropes are scrambled into a kind of super-internet pastiche. His ride’s a sensible Smart car; his crew, sullen adolescents from Stockholm who call themselves the Sad Boys. Beside him sits not Cristal but a bright pink My Little Pony. And there’s Lean himself: a chubby-cheeked cherub, more Directioner than Chicago South Side, who deadpans about being a “lonely cloud”. “We just thought it was funny,” he says later. “I’m not really into My Little Pony, I’m not a ‘Brony’, just to clear that up.”

At first, Yung Lean’s Yoshi City video is just like any other young up-and-coming rapper’s. The teenager hangs out of a moving car surrounded by his crew. There’s a phone in his hand, a fag in his mouth. But the familiar rap tropes are scrambled into a kind of super-internet pastiche. His ride’s a sensible Smart car; his crew, sullen adolescents from Stockholm who call themselves the Sad Boys. Beside him sits not Cristal but a bright pink My Little Pony. And there’s Lean himself: a chubby-cheeked cherub, more Directioner than Chicago South Side, who deadpans about being a “lonely cloud”. “We just thought it was funny,” he says later. “I’m not really into My Little Pony, I’m not a ‘Brony’, just to clear that up.”

There’s something about watching small planes land on one runway of Gdynia’s Babie Doły Military Airport while you’re watching The Black Keys headline a festival from the other which lets you know that Open’er is not like other festivals. Located on a sprawling airfield in northern Poland, things don’t tend to get started until gone 6pm – which is pretty civilised for those of us who are staying in the nearby beach resort town of Sopot. The festival site serves hundreds of gallons of Heineken each year but frowns on spirits, giving it a reputation as the sort of place serious music fans come to watch music, not just get out of their heads. That could be part of the reason they attract some of the world’s biggest bands and most exciting new artists here to entertain 60,000 Pole dancers over four days.

There’s something about watching small planes land on one runway of Gdynia’s Babie Doły Military Airport while you’re watching The Black Keys headline a festival from the other which lets you know that Open’er is not like other festivals. Located on a sprawling airfield in northern Poland, things don’t tend to get started until gone 6pm – which is pretty civilised for those of us who are staying in the nearby beach resort town of Sopot. The festival site serves hundreds of gallons of Heineken each year but frowns on spirits, giving it a reputation as the sort of place serious music fans come to watch music, not just get out of their heads. That could be part of the reason they attract some of the world’s biggest bands and most exciting new artists here to entertain 60,000 Pole dancers over four days.

This is the VICE Guide to Europe 2014. A travel guide featuring: pork, anarchists, bicycles, politicians, fishermen, racists, tear gas, cocaine, pizzas, techno, beer, football fans, bands and waiters.

This is the VICE Guide to Europe 2014. A travel guide featuring: pork, anarchists, bicycles, politicians, fishermen, racists, tear gas, cocaine, pizzas, techno, beer, football fans, bands and waiters.

Yes, the build-up to today’s European elections has been dominated entirely by a one-man publicity machine. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other groups of narcissists out there who aren’t at least as deserving of your attention. So, before you go to cast your vote for UKIP, let’s review some party political broadcasts from other groups – groups who also refuse to adhere to the staid PR conventions of Westminster’s “Big Three”, like using decent microphones and not putting giant CGI monsters in your videos.

Yes, the build-up to today’s European elections has been dominated entirely by a one-man publicity machine. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other groups of narcissists out there who aren’t at least as deserving of your attention. So, before you go to cast your vote for UKIP, let’s review some party political broadcasts from other groups – groups who also refuse to adhere to the staid PR conventions of Westminster’s “Big Three”, like using decent microphones and not putting giant CGI monsters in your videos.

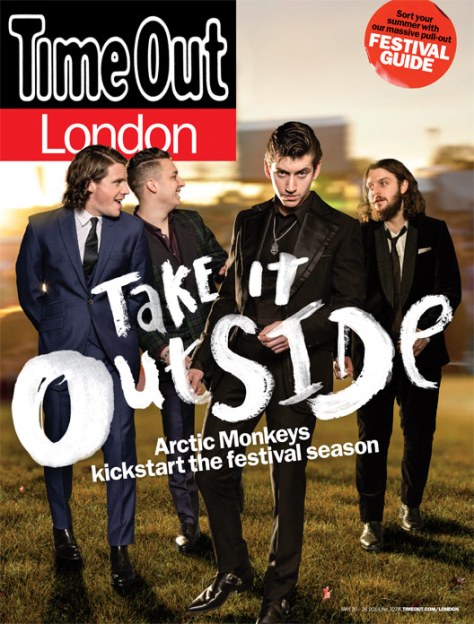

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

When US singer-songwriter Elliott Smith died in 2003, aged just 34, he left behind him not only a beautiful and introspective body of work stretching over five albums and including the Oscar-nominated ‘Miss Misery’, but also a host of unreleased demos and song ideas.

When US singer-songwriter Elliott Smith died in 2003, aged just 34, he left behind him not only a beautiful and introspective body of work stretching over five albums and including the Oscar-nominated ‘Miss Misery’, but also a host of unreleased demos and song ideas.

There’s this guy who paints houses for a living. He has a pick-up truck and a pug dog, who he loves very much. The guy has to change his health insurance so he goes for a check-up, and afterwards they ask him to come in to talk about his results with a counsellor, which is never good news. So he goes in and he’s sat across the desk from this well-dressed, middle-aged woman with a folder of results. She says: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but you’ve tested positive for HIV.”

There’s this guy who paints houses for a living. He has a pick-up truck and a pug dog, who he loves very much. The guy has to change his health insurance so he goes for a check-up, and afterwards they ask him to come in to talk about his results with a counsellor, which is never good news. So he goes in and he’s sat across the desk from this well-dressed, middle-aged woman with a folder of results. She says: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but you’ve tested positive for HIV.”

When was the last time you went online? Within the last hour? The last five minutes? Are you, in fact, checking your emails on your phone with one hand while you flip through this magazine? Are you half-wondering what you might tweet about it?

When was the last time you went online? Within the last hour? The last five minutes? Are you, in fact, checking your emails on your phone with one hand while you flip through this magazine? Are you half-wondering what you might tweet about it?

When Colombian National Police finally put a bullet through Pablo Escobar’s head in December 1993, he was running what was probably the most successful cocaine cartel of all time, worth some $25 billion (£15 billion). You can do pretty much anything you want with that kind of money, and Escobar did, building houses for the poor, getting himself elected to Colombia’s Congress and running much of the northeastern city of Medellín as his own personal fiefdom.

When Colombian National Police finally put a bullet through Pablo Escobar’s head in December 1993, he was running what was probably the most successful cocaine cartel of all time, worth some $25 billion (£15 billion). You can do pretty much anything you want with that kind of money, and Escobar did, building houses for the poor, getting himself elected to Colombia’s Congress and running much of the northeastern city of Medellín as his own personal fiefdom.

Pussy Riot members Nadia Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina have called for economic sanctions against Russia in the wake of their country’s military action in the Ukraine.

Pussy Riot members Nadia Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina have called for economic sanctions against Russia in the wake of their country’s military action in the Ukraine.

My Wednesday at SXSW 2014 started with the surreal experience of wandering into a rented kitchen in the east of the city to find Kelis hard at work preparing jerk chicken and other tasty treats for her own food truck. Be assured that her ‘Feast’ line of sauces are no ordinary celebrity endorsement – Kelis is a trained saucier and the sort of boss that all her kitchen staff refer to her as ‘chef’. We’ll find out today whether her jerk chicken brings all the boys to the yard.

My Wednesday at SXSW 2014 started with the surreal experience of wandering into a rented kitchen in the east of the city to find Kelis hard at work preparing jerk chicken and other tasty treats for her own food truck. Be assured that her ‘Feast’ line of sauces are no ordinary celebrity endorsement – Kelis is a trained saucier and the sort of boss that all her kitchen staff refer to her as ‘chef’. We’ll find out today whether her jerk chicken brings all the boys to the yard.

In an anonymous but well-fortified lean-to somewhere down a back alley in South London, Graham Johnson is deep in conversation with a man he describes as a “local warlord”. Johnson is a usually a talkative Scouser, but at the moment he’s letting the physically imposing figure who greeted me with a finger-crushing handshake hold court. Johnson explained earlier that the guy’s business is “protection, in the nicest possible way.” He rarely grants this sort of audience. He’s a busy man. Wholesale drug dealers and fraudsters pay him insurance money, and in return they can operate safe in the knowledge that they’re protected against theft by other gangs. Above the gangster’s desk are pinned remembrance cards from the funerals of a host of London underworld figures, and under the watchful eyes of Ronnie Biggs he’s currently telling a wildly entertaining story about the time he extorted compensation money for a drug dealer who’d be dobbed in to the police by a family member. He’d made sure the snitch paid the dealer’s family £20,000 “plus a Big Mac” for him. The deal almost went south when they forget to bring him his Big Mac. In short, Guy Ritchie would cast this guy without a second’s hesitation.

In an anonymous but well-fortified lean-to somewhere down a back alley in South London, Graham Johnson is deep in conversation with a man he describes as a “local warlord”. Johnson is a usually a talkative Scouser, but at the moment he’s letting the physically imposing figure who greeted me with a finger-crushing handshake hold court. Johnson explained earlier that the guy’s business is “protection, in the nicest possible way.” He rarely grants this sort of audience. He’s a busy man. Wholesale drug dealers and fraudsters pay him insurance money, and in return they can operate safe in the knowledge that they’re protected against theft by other gangs. Above the gangster’s desk are pinned remembrance cards from the funerals of a host of London underworld figures, and under the watchful eyes of Ronnie Biggs he’s currently telling a wildly entertaining story about the time he extorted compensation money for a drug dealer who’d be dobbed in to the police by a family member. He’d made sure the snitch paid the dealer’s family £20,000 “plus a Big Mac” for him. The deal almost went south when they forget to bring him his Big Mac. In short, Guy Ritchie would cast this guy without a second’s hesitation.

Dubai’s towering skyline has erupted from the desert in just two decades, and if you’re one of the ten million tourists who visit each year you’ll know that it’s a town built on excess. It’s a city of glass summoned into reality in the middle of a desert. Pity the tireless window cleaners. Everything must be bigger and grander than everything else that’s gone before – and after a while, it all gets a bit much. When a man is tired of Dubai, where does he go?

Dubai’s towering skyline has erupted from the desert in just two decades, and if you’re one of the ten million tourists who visit each year you’ll know that it’s a town built on excess. It’s a city of glass summoned into reality in the middle of a desert. Pity the tireless window cleaners. Everything must be bigger and grander than everything else that’s gone before – and after a while, it all gets a bit much. When a man is tired of Dubai, where does he go?

Rudimental are four impossibly upbeat boys from Hackney who are the new kings of the all-night party anthem. Last year’s debut album ‘Home’ was packed with more bangers than a family-size toad in the hole, and it rightfully earned them three BRIT Award nominations: Best Group, Best Album and Best Single (for ‘Feel the Love’).

Rudimental are four impossibly upbeat boys from Hackney who are the new kings of the all-night party anthem. Last year’s debut album ‘Home’ was packed with more bangers than a family-size toad in the hole, and it rightfully earned them three BRIT Award nominations: Best Group, Best Album and Best Single (for ‘Feel the Love’).