Have you ever pictured The Rolling Stones as the heroes of their own picaresque novel – the rogueish heroes battling their way through a corrupt and venal society as sketched by Dickens, Thackeray or Henry Fielding? Probably not, to be honest, yet you have to admit the idea of Jagger and Richards cocking a snoot at authority and living on their wits does make a certain amount of sense. It made so much sense to Simon Goddard, author of Ziggyology and Mozipedia, that he’s reimagined the story of the band in Rollaresque, a new novel, complete with sketch illustrations by Mr Chadwick. I spoke to Goddard to find out why he wanted to retell the ‘rakish progress’ of The Rolling Stones…

Have you ever pictured The Rolling Stones as the heroes of their own picaresque novel – the rogueish heroes battling their way through a corrupt and venal society as sketched by Dickens, Thackeray or Henry Fielding? Probably not, to be honest, yet you have to admit the idea of Jagger and Richards cocking a snoot at authority and living on their wits does make a certain amount of sense. It made so much sense to Simon Goddard, author of Ziggyology and Mozipedia, that he’s reimagined the story of the band in Rollaresque, a new novel, complete with sketch illustrations by Mr Chadwick. I spoke to Goddard to find out why he wanted to retell the ‘rakish progress’ of The Rolling Stones…

Category Archives: NME

Lusts

It was while trawling round Paris in search of the ghosts of Oscar Wilde and Ernest Hemingway that Andy Stone and his younger brother James were inspired to start a band. “We met some cool people and ended up going to loads of parties,” says Andy. “We realised it’s not just about visiting these old haunts, it’s about finding the equivalent scene now.”

It was while trawling round Paris in search of the ghosts of Oscar Wilde and Ernest Hemingway that Andy Stone and his younger brother James were inspired to start a band. “We met some cool people and ended up going to loads of parties,” says Andy. “We realised it’s not just about visiting these old haunts, it’s about finding the equivalent scene now.”

They did seek inspiration from decadent French poet Rimbaud though, even if they couldn’t actually understand him. “James bought me Rimbaud’s Illuminations for my birthday, but he bought the French edition by mistake,” explains Andy. “We wrote a song based on what we envisioned the book might be about. One of the good things about being brothers is that it doesn’t matter so much when one of us does something fucking weird, it can still spark something off.”

Beach House in the studio

Th eir band may be called Beach House, but when Baltimore dream-pop duo Victoria Legrand and Alex Scally were ready to record their fifth album they headed to a little place in the country. “It’s called Studio in the Country,” explains Scally, “and it was built in the 70s to be a premier studio way out in the middle of nowhere in Louisiana. Stevie Wonder recorded there, and Kansas recorded ‘Dust In The Wind’ there. It was the spot for a little while. It’s such a cool studio, but in the worst possible place. Studios are the coolest places in the world, but nobody even goes to them anymore because no-one wants to spend the money.”

eir band may be called Beach House, but when Baltimore dream-pop duo Victoria Legrand and Alex Scally were ready to record their fifth album they headed to a little place in the country. “It’s called Studio in the Country,” explains Scally, “and it was built in the 70s to be a premier studio way out in the middle of nowhere in Louisiana. Stevie Wonder recorded there, and Kansas recorded ‘Dust In The Wind’ there. It was the spot for a little while. It’s such a cool studio, but in the worst possible place. Studios are the coolest places in the world, but nobody even goes to them anymore because no-one wants to spend the money.”

Rocky All Over The World

The 1,000-square-foot Wedgewood Suite at London’s opulent Langham Hotel, all antique bookcases and porcelain horses, looks like the sort of place minor royalty would stay if Buck Palace was overbooked. The sofa alone probably costs more than a decent family car, but this is no time to get distracted by the upholstery.

The 1,000-square-foot Wedgewood Suite at London’s opulent Langham Hotel, all antique bookcases and porcelain horses, looks like the sort of place minor royalty would stay if Buck Palace was overbooked. The sofa alone probably costs more than a decent family car, but this is no time to get distracted by the upholstery.

“Do you mind if I roll up some bud?” asks 26-year-old hip-hop icon A$AP Rocky. He grins and heads off into another room to retrieve a bag of weed and a pack of Backwoods cigars, one of which he deftly unrolls so he can make a blunt.

Rocky is sharing the suite with Joe Fox, a young British singer and guitarist who featured on five tracks on Rocky’s most recent album, ‘At.Long.Last.A$AP’, which came out at the end of May. The story of how Rocky and Joe Fox met is so good that most people assume it’s made up, but both men swear this is how it happened: Rocky was leaving Soho’s Dean Street Studios at around 4am after a long night of recording. Joe approached him, not recognising him, hoping to sell him a CD. Rocky asked Joe to play a song. He did, Rocky loved it, they jumped in an Uber and the rest is history. Joe, who was homeless at the time, moved into Rocky’s hotel room and jumped straight from busking on the streets to appearing on an American Billboard Number One album.

“When I met him, he had this weird energy,” Rocky says of Joe, who’s currently out. “He was so full of hope and light. We totally disregarded the fact that he was homeless. What mattered was that he had a voice and I knew that the world needed to hear it.”

It’s also clear that Rocky sees Joe as a kindred spirit. “He has so many chicks, man,” Rocky says. “It’s weird, because he always had chicks but… Jesus, man. I’m impressed because I never seen someone get chicks like him – unless they were A$AP.”

Meeting Joe in London just one of the reasons Rocky has come to think of the capital as his adopted home. He recorded 15 of ‘At.Long.Last.A$AP’s 18 tracks in the city, either at Dean Street or Red Bull Studios. It had been his dream to come to the city since he was 14. “I really love it, man,” he says. “I don’t know what it is. The energy kinda reminds me of New York, but better.”

Rocky has built a circle of London-based friends and collaborators that takes in everyone from cloud rap crew Piff Gang to Sam Smith, who he ran into late last night at Soho House. “Coming here feels nostalgic to me,” he says. “There’s some sort of connection, like I belong here. I can’t really explain being from somewhere else and claiming another place! I never thought I would have to explain that in life, but apparently here we are.”

Rocky was actually born in Harlem, New York, named Rakim Mayers after hip-hop legend Rakim. He made his name with the woozy 2011 mixtape ‘Live.Love.A$AP’, which demonstrated his ability to assimilate numerous rap styles, while also introducing the rest of Harlem’s A$AP Mob (including rappers A$AP Ferg and A$AP Nast) to the world. 2013’s major label debut ‘Long.Live.A$AP’ was a more conventional affair, spawning international mega-hits ‘Fuckin’ Problems’ and Skrillex collaboration ‘Wild For The Night’ (62 million and 42 million YouTube views respectively). Yet Rocky’s experimental new record ‘At.Long.Last.A$AP’ feels like another left-turn. This is deliberate: he’s intent on rejecting the pop world he courted on his last album.

“Think about where mainstream is, and how far from mainstream my music is,” he says. “The biggest artists have to make pop music. I know how to make that music, I just hate it. Pop sounds like some Space Jam bubblegum fucking shit. If you listen to my first mixtape and you listen to the last album, they kind of connect. That middle project had a few mainstream joints on there. Whatever. I had a song with Florence + The Machine on there [‘I Come Apart’].” He gives the impression that the Florence collaboration was a label exec’s idea of what he should be doing to cross over, whereas the collaborators on his new album were strictly hand-picked – even Rod Stewart, who he calls a “jiggy motherfucker”.

Rocky draws languidly on the blunt. While smoking weed everyday isn’t rare in the rap world, his musical experimentation has been coloured by the embrace of more psychedelic drugs. “LSD freed me from a lot,” he explains. “Where I come from, recreational drugs are like marijuana or something like that. Shit like acid is foreign. Only white people do it, that’s the mentality in the hood.”

He begins to tell me the story of the first time he ever had a proper acid trip – here in London, with LSD – when he’s interrupted by a knock at the door.

“This is the infamous Joe Fox,” says Rocky, by way of introduction.

“Are you doing an interview?” Joe asks.

“Yeah, but sit down, chill,” says Rocky. “It’s good vibes, man.”

Fox spots the blunt. “Oh, it’s lit.”

“It’s always lit. You know it’s always lit,” chides Rocky. Joe sits down on the sofa, but barely has time to get comfortable before Rocky asks: “So you fuck both of them bitches last night?”

“Just one,” says Fox.

“Ahh, shit!” sighs Rocky. “It’s weird, motherfuckas don’t just want to be fucking one bitch no more. It’s two or better.”

“You have to remember that that’s not how society does it,” laughs Fox. “Sometimes you’re like: ‘Oh yeah, threesomes aren’t normal’.”

“You want to know something though?” asks Rocky. “I think threesomes are normal now.”

“They’re normal to you,” says Fox.

“I’ll tell you this much,” says Rocky, “before I was famous, they weren’t normal but I damn sure was trying every chance I got, and I got lucky sometimes. Now it’s common. It’s just sex, man. I love a woman with confidence who’s comfortable with her sexuality. I’m a weirdo: I don’t want a virgin. I don’t. That’s boring. You’re gonna cheat on that girl, man. What about a girl that’s open-minded? What about a girl who knows that you’re a man and sometimes you might slip? I need to be honest enough to be able to tell that girl: ‘I messed up last night, and I fucked another girl.’ I don’t expect it to be OK, I expect repercussions, but I expect the friendship to be able to stand it.”

Rocky’s talk of women and sex is not held back by the recent furore over his song, ‘Better Things’, which contained the following lyrics: “I swear that bitch Rita Ora got a big mouth / Next time I see her might curse the bitch out / Kicked the bitch out once cause she bitched out / Spit my kids out, jizzed up all in her mouth and made the bitch bounce.” He must have known how nastily misogynistic those lines are, so was he expecting the repercussions?

“I thought it was going to be like the ’90s,” he shrugs, “and people would let art be art.”

He laughs at his own faux-naivety, but continues: “You know, when you had Eminem saying all types of shit he didn’t have to explain that shit in interviews or on the radio or on camera or shit. People just said what they said and you had to listen to the next song to hear how they felt.”

Does he understand why people call him a sexist? “No, not at all. I think it’s a misunderstanding. When I talk about an experience I’ve had with a woman, I’m talking about an experience. That’s that. I don’t go around saying women are just hos. Do I think they’re less of a person compared to a man and the human race? No.”

Rocky argues that he doesn’t even talk about sex that often in his lyrics. “I don’t really talk about the orgies too much. I do love bad bitches, I do have a fuckin’ problem, but that’s really old. The only time I talked about orgies in the press was that one time doing LSD at SXSW. That was a big deal because I was high. Man, it was incredible.”

How often does he sleep with a new woman?

“I meet chicks. I don’t fuck a new chick every night… or do I?” Rocky seems genuinely unsure at this point. “I don’t… do I, Joe?”

“If you average it out, man,” replies Fox, sagely. “Sometimes I think you do that shit to be time effective. You’ll sleep with six girls in a night just so you can work for five days.”

That’s too big a claim even for Rocky’s ego. “Nah, he’s lying! I do not sleep with six girls a night. I might sleep with three girls at once but not every day. That’s lying on my own penis if I said that.”

When he reflects on his behaviour, Rocky suggests he’s motivated by a sense of mortality – particularly after the deaths of his father at the end of 2012, and his friend and collaborator A$AP Yams, who died in January this year. “I’m 26 and people try to pressure me to be like this role model,” he says. “I’m not no role model because I’m not perfect. I’m only human. When you ask a guy who’s 26, who’s been famous for barely three years, really, and who lost his father and his best friend and Robin Williams in that whole time period… I look at life like I need to be having motherfuckin’ orgies!”

As such, he’s reluctant to comment on politics. Referring to his recent talk at the Oxford Union, he says: “I was asked a question about whether I think it’s important for as an artist like me to talk about what’s going on in Ferguson and Baltimore, and the police brutality towards urban people in America. I was like: ‘I have an opinion on that, but as far as the subject matter I don’t really think that’s something I should be talking about unless I’m making a difference. I was in London recording the whole time this shit has been going down. For me, I’m in it because obviously I’m from America, my people are from America and I’m black but at the same time my reach isn’t only to them. If I have a responsibility, it wouldn’t only apply to black people. Right now, why are people trying to pressure me to be a fuckin’ spokesperson when in reality my art reaches out to all people of different backgrounds? The culture, the movement, is bigger than one race.”

So what does Rocky see as his artistic responsibilities? “It’s my responsibility as a black man and as an artist to inspire and to make a way and shed light on how to be successful or artistic and express yourself to the youth. That’s what my job is.”

Rocky feels at home doing that job in London. Here in Britain, he’s found plenty of like-minded souls willing to indulge his appetite for sex, drugs and making trippier music. While recording ‘At.Long.Last.A$AP’ he stopped worrying about trying to please the world. “If people like pop music, and the masses love it apparently, then I think the masses like shitty music. How many billion people were listening to ‘Gangnam Style’? This album I think is dope. I think it’s hard. Either you like it or you hate it, and that’s fine. I don’t expect everybody to like it.”

He drops the dying blunt into a fine china teacup. “A$AP Rocky is not for everybody, clearly.”

Open’er 2015: Father John Misty says he has “no interest in writing about love anymore”

Josh Tillman, who performs as Father John Misty, has written my favourite album of the year: ‘I Love You, Honeybear’. I spoke to him on his tourbus backstage at Poland’s Open’er Festival 2015:

What can you tell me about the writing of ‘Chateau Lobby #4 (in C for Two Virgins)’?

“To be honest, the details around that song are pretty salacious, and I’m not sure I want them circulating in the British imagination. It’s really just a tune about the first few months of being in love with someone. It’s definitely the most sentimental thing I’ve ever written, which gave me some problems when it came time to record it. In terms of the context of the album… I know the music media isn’t crazy about context… but within the context of the album I feel like it gives the other tunes… I feel like the song has a chance to breath. It’s sort of a welcome respite from the very thorough angst of the rest of the album. Isn’t that a great story, that I just told? A classic. Tell it again! Tell the story about ‘Chateau Lobby #4’!”

How did your wife react when you played it to her?

“She went ‘Ah!’” [Clutches bosom]

Was that the desired effect?

“Yeah, yeah. Actually, it was more like ‘Ah!’” [Smiles and clutches bosom]

Did you feel comfortable sharing so much detail about your life?

“I’d be in the wrong business… you know? I think that’s just the job. I’m grateful to have something to share, you know what I mean? I definitely was writing some real bullshit for a little while, between these two albums and before meeting Emma. [I’m inside, I’m gonna take these off. I’m inside.] I think the anxiety about sharing comes after the fact. During the mixing phase I remember having quite a bit of anxiety. It’s part of the deal.”

And your wife doesn’t mind?

“No, I mean she’s kinda the one… I mean, our lives are one and the same, at this point, and we both view it that way. I think that she was very much the person holding me accountable as an artist, because my instinct was to obscure how personal and how meaningful the songs, and the experiences therein, were to me. My instinct is to kind of, if I can, inject some element of ‘Just kidding!’ to the songs. I tried that and it just wasn’t… it was horrible. The songs just laid there like wet shit, when that attitude was applied to it. She was very much the person who was like: ‘You need to be a man. You wrote these songs, and now you must suffer the consequences.’ She’s very inspirational in that regard.”

I take it she has a highly-attuned bullshit sensor.

“Well yeah, we both do. That’s part of the reason we work. More often that not… I don’t believe in love as a ‘thing’. I don’t believe you can write about love as a ‘thing’. I think love is a context. It’s a perspective, you know? It’s a perspective that allows you to address things honestly, which is I think the irony in the fact that so many love songs are rooted in some kind of fantasy that I don’t recognise. If you have love at your disposal, if you have that perspective, I think you’re able to look at things for what they really are. I think that’s what’s exciting to me about having intimacy with another person who’s willing to kind of go that much further inside yourself, and inside the other person. Literally and figuratively. Anyway…” [Waggles eyebrows].

Is there a nod to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Chelsea Hotel No. 2’ in the title?

“Oh, the numeral? I don’t know why he has that… maybe… no, that wasn’t the intention. I recorded the song like four times, kinda for the reasons I was describing earlier, where it was just like I couldn’t get to what was vital about the song, because what was vital about the song was it’s sort of blind romanticism, and that was what I was having such a hard time acknowledging. It had that component, and it just needed to be acknowledged. It needed horns and whatever else it needed. It needed exuberance, which isn’t typically my forte.”

You usually mask it with gags?

“Yeah, I mean not the gags so much, but just the unchecked angst, or the unchecked scepticism about myself, and about the whole enterprise of love or intimacy.”

It seems to be counterbalanced by songs like ‘The Night Josh Tillman Came To Our Apt.’

“It’s a love song. It’s very devotional. Any time you write a song about someone, any time someone inspires you enough to write a song, whether it’s been distorted or not, distorted by ego or whatever, it’s still devotional. It’s passion. Everybody knows this shit, but love and hate… are not so different. Deep thoughts!”

Speaking of Leonard Cohen, your cover of ‘I’m Your Man’…

“I love that song.”

Seems to contain a lot of the DNA…

“Oh, absolutely.”

…of the Father John Misty character

“Yeah…? What character? It’s not a character. It’s just a name. It’s just a sequence of phonetic sounds. He doesn’t exist. There’s no cartoon character, do you know what I mean? But I feel like that song is good extra credit in terms of the album and the issues that I wanted to address. I think in that song he’s posing this age old question of ‘What is it that a woman wants from a man?’ It’s like: they want everything. It’s the same thing with men. What do men want out of a woman? What does anyone want out of a companion? They want everything. They want what they need when they need it. It’s incredible. That’s our attitude towards everything. It’s our attitude towards God, and life, and other people. We’re very reckless when it comes to what we need. I love acknowledging that. So often songs say: ‘I will be whatever you need’ or ‘I can be whatever you need’, which is bullshit. Coming out and saying: ‘I need everything. I need you to be everything’ is really cathartic. It’s great.”

Where do you go from here? Will you continue to write about love?

“I have no interest in writing about love anymore, or for a while. I’m kinda worn out on that. I’m proud of it. I feel like for me it was an accomplishment because, at the time that I undertook it, it felt so far out of my wheelhouse. Right now… I have the next album written.”

What’s it about?

“Well, I don’t want to confuse the issue. I feel like writing about intimacy afforded me a really unexpected level of clarity, so turning that perspective outwards is essentially what the next album is all about.”

So more along the lines of ‘Bored In The USA’?

“I would say ‘Bored In The USA’ and ‘Holy Shit’. Those two are a good indicator of where I’m going. The album after that is just pure vodka. Just The Vodka Album… I don’t know what that means.”

Does being in a happy and stable relationship change the sort of things you want to write about?

“I don’t know. Happiness and stability means different things to different people. Like I was just saying about clarity, I definitely think it broadens your perspective and broadens what you’re able to write about. At the time that I wrote ‘Fear Fun’ I was convinced that all I could really write about was getting fucked up and being bummed about it. I thought that anything outside of that I was out of my depth. I was really surprised at the outcome of going into such unchartered territory for myself with this one. I really don’t… certainly at some point I will absolutely run out of juice. It happens to everybody. I will put out some really… I’m sure there’s some horrible music from me on the horizon, but I’m not sure that that’s just yet.”

Interviewed for NME.

Glastonbury 2015: Patti Smith joined by the Dalai Lama

There are some things that could only ever happen at Glastonbury, and Patti Smith welcoming the Dalai Lama onstage midway through her electric show on the Pyramid Stage to wish him a happy birthday is undoutbtedly one of them. His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who earlier spoke about the importance of global unity and oneness at the Stone Circle, will turn 80 on July 6. As an early birthday present Smith read a new poem that she had written for the occasion:

There are some things that could only ever happen at Glastonbury, and Patti Smith welcoming the Dalai Lama onstage midway through her electric show on the Pyramid Stage to wish him a happy birthday is undoutbtedly one of them. His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who earlier spoke about the importance of global unity and oneness at the Stone Circle, will turn 80 on July 6. As an early birthday present Smith read a new poem that she had written for the occasion:

Thai For Heroes

In Thailand, they have a saying about deeply improbable events. They say châat nâa dton-bàai, meaning it will happen ‘one afternoon, in your next reincarnation’. In England, we’d say ‘when hell freezes over’ or ‘when The Libertines record a new album’. Yet, somehow that most improbable of days has arrived. For the first time in over a decade, Pete Doherty and Carl Barât sat down nose to nose and wrote new songs together. Then they recorded them with bassist John Hassall and drummer Gary Powell over a five-week period at Thailand’s Karma Sound studios. From that studio built on an old snake pit, where recording sessions were punctuated by visits to the notorious vice den of Pattaya, their third album has finally emerged. It’s the moment anyone who ever dreamed of Albion has been waiting ten years for – the Libertines included. “People are going to love it,” says Pete, who’s still ensconced in his Thai bolthole, “There’s a miracle aspect to actually getting it done and all getting together to do it. We’re all really proud of it.” “It’s unbelievable,” says Carl, back in London and still sounding like he can scarcely believe what’s going on. “It’s staggering that we’ve got to the point where we’ve actually got an imminent release for the fucking Libertines. Are you kidding me? Honestly, I’m still kind of pinching myself. Is this really going to happen? It’s mental, but I guess it is.”

In Thailand, they have a saying about deeply improbable events. They say châat nâa dton-bàai, meaning it will happen ‘one afternoon, in your next reincarnation’. In England, we’d say ‘when hell freezes over’ or ‘when The Libertines record a new album’. Yet, somehow that most improbable of days has arrived. For the first time in over a decade, Pete Doherty and Carl Barât sat down nose to nose and wrote new songs together. Then they recorded them with bassist John Hassall and drummer Gary Powell over a five-week period at Thailand’s Karma Sound studios. From that studio built on an old snake pit, where recording sessions were punctuated by visits to the notorious vice den of Pattaya, their third album has finally emerged. It’s the moment anyone who ever dreamed of Albion has been waiting ten years for – the Libertines included. “People are going to love it,” says Pete, who’s still ensconced in his Thai bolthole, “There’s a miracle aspect to actually getting it done and all getting together to do it. We’re all really proud of it.” “It’s unbelievable,” says Carl, back in London and still sounding like he can scarcely believe what’s going on. “It’s staggering that we’ve got to the point where we’ve actually got an imminent release for the fucking Libertines. Are you kidding me? Honestly, I’m still kind of pinching myself. Is this really going to happen? It’s mental, but I guess it is.”

Cover story for NME, 20 June 2015. Continue reading.

Professor David Nutt on legal high ban: “The government are miserable sods”

Last week, the Government announced that it’s going to outlaw “any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect” – except from those it deigns to allow like caffeine, certain medicines and booze. It’s a move which in theory means the end of the road for nitrous balloons, poppers and that stash of legal highs being sold next to the bongs at festival stalls and in your local head shop. While some might celebrate the fact that you’ll no longer be kept awake in your tent by the insistent ‘woosh’ of balloons being filled, a lot of people will probably see it as a dark day for civil liberties and personal choice. Also, given the difficulty of policing this area, the law may not have much practical use at all. To get an expert’s opinion on what the new law will mean, I spoke to Professor David Nutt, the government’s former chief drug advisor. Since his sacking in 2009, Professor Nutt has been campaigning for drugs policy to be based on scientific evidence rather than political whim. He told me why he believes the new law is “pathetic” – an attack on fun by the government’s “miserable sods”:

Last week, the Government announced that it’s going to outlaw “any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect” – except from those it deigns to allow like caffeine, certain medicines and booze. It’s a move which in theory means the end of the road for nitrous balloons, poppers and that stash of legal highs being sold next to the bongs at festival stalls and in your local head shop. While some might celebrate the fact that you’ll no longer be kept awake in your tent by the insistent ‘woosh’ of balloons being filled, a lot of people will probably see it as a dark day for civil liberties and personal choice. Also, given the difficulty of policing this area, the law may not have much practical use at all. To get an expert’s opinion on what the new law will mean, I spoke to Professor David Nutt, the government’s former chief drug advisor. Since his sacking in 2009, Professor Nutt has been campaigning for drugs policy to be based on scientific evidence rather than political whim. He told me why he believes the new law is “pathetic” – an attack on fun by the government’s “miserable sods”:

Laughing gas balloons have become incredibly popular at festivals over the last few years. How dangerous is inhaling nitrous oxide?

“Well, if you take one of the canisters that they use for treating women in childbirth for four or five days then you will certainly end up damaging the vitamin B in your blood, but two balloons every hour for a couple of hours aren’t going to affect anyone. Outlawing nitrous oxide truly is pathetic. Some of the greatest minds in the history of Britain, the people that made British science, used nitrous oxide. Wordsworth and the Romantic poets used nitrous oxide. The guy who popularised the use of nitrous oxide, Humphry Davy, was friends with Wordsworth and Coleridge. Nitrous oxide has been around as a medicine and a way of people understanding a different way of feeling for 200 years. Banning it now is pathetic. They’ll be putting yellow stars on drug takers’ foreheads soon. It is a peculiar attack on being anything other than a member of the Bullingdon Club – but they did drugs, didn’t they? I think this is just about young people enjoying themselves, and they hate that because they’re miserable sods.”

Why do you think the government is bringing this law in?

“What’s going on is that they want to stop people using highs that are sold at head shops. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but it’s been driven by an organisation called the Local Government Association, and these people hate the idea of head shops. They’re supported by Police Exchange, which is a very right wing group. They’re basically an outpost of right wing US Republican thinking on drugs. What they want to do is get rid of head shops because they don’t like the idea that head shops could be doing anything useful. They may also be funded by the drinks industry at arm’s length… I’ve got no proof of that, but it wouldn’t surprise me. They want to get rid of head shops because they don’t like the idea of people doing drugs other than alcohol, for reasons I don’t understand. They concocted this lie that 97 people died last year from legal highs, which is not true. Of those 97 deaths, almost all of those were related to illegal drugs. They’ve concocted and continue to perpetuate this lie. In fact, my view is that there are almost no deaths from legal highs at all. There are millions of people using them, but the most dangerous ones have disappeared. I don’t think there are any really dangerous legal highs out there at present – but this is about politics, it isn’t about saving people’s lives. What will happen is this will drive people onto the internet or underground. No-one will know what they’re getting and there will be no quality control. In head shops, people are largely getting what they wanted. Now it will all be underground or on the internet, and my own personal belief is that harms will rise significantly.”

Will they actually be able to police the sale of poppers and nitrous oxide?

“Well you can buy poppers to disinfect your house. You can buy poppers in the supermarket, and you can buy nitrous oxide to foam up your cream. Are they going to stop people doing that? They haven’t thought this through. It’s all just a silly gesture. They’ve said they won’t prosecute people for possession or for personal use but they will prosecute people trying to sell it. The Act isn’t clear at present, but we think that trying to purchase it on the internet might end up being an offence. I think people will get around that, but they could in theory be prosecuted for buying stuff knowing that it was going to change their brain.”

How will they choose which substances are exempt from the ban?

“The Home Secretary will make her mind up and a drug will be in or out depending on her whim. It doesn’t appear that they’re going to take any notice of what scientists say. She’s going to decide whether a drug is a psychoactive or not. They’re going to exempt tea, coffee, alcohol… and I don’t know what else. Probably antidepressants, antipsychotics and all that sort of stuff. They haven’t defined what a psychoactive substance is. Most medical treatments of the brain are psychoactive. It hasn’t been thought through at all. It may all flounder because it may be impossible to write a law that isn’t so full of holes it disintegrates. On the other hand, they could just write a law which is useless, like in Ireland which encorages deaths because of backstreet use. Deaths in Ireland have gone up since they banned head shops, not gone down.”

Because people don’t know what they’re getting?

“Absolutely, and also because when you’re going to illegal dealers you’re also going to be offered heroin and cocaine. Heroin has been illegal for 50 years and we still have 1,200 deaths from people seeking opiates. It’s not as if banning has ever been shown to work. In fact, we know it doesn’t work because most of the drugs involved in those 97 deaths are banned – but people are still using them. They’re not being sold in head shops, by the way. The deaths are not coming from head shops. The deaths are coming from people getting them illegally. Head shops don’t sell illegal drugs. They’re the good guys. They’re selling drugs which are known to be relatively safe. Attacking head shops is like attacking sex shops because you think they lower the tone of your town.”

Given the difficulty of policing this area, do you think this law will actually have a big impact or is it just political grandstanding?

“I think it will make things a lot worse. Head shops will struggle. They may go back to selling these substances to as ‘bath salts’ or ‘plant food’. Then there will be some test prosecutions. It’s difficult to know. One suspects the law actually may fail if it’s enacted and there are test prosecutions which fail. That will be some time away, and a lot of head shops may just give up because they decide it’s not worth the effort. Trying to offer a safer alternative to alcohol is not really appreciated in this country – which is kind of weird, really. You want to deny people a safer drug than alcohol? It’s a weird, weird world. Science is out the window here. This is all politics.”

The Great Escape 2015: Fraser A Gorman

Fraser A Gorman has a distinct memory of the first time he ever met his now-label boss Courtney Barnett after moving to Melbourne as an 18-year-old. “I met her in a bar and tried to pick her up,” he laughs, “Which is kinda funny because she likes girls.”

Fraser A Gorman has a distinct memory of the first time he ever met his now-label boss Courtney Barnett after moving to Melbourne as an 18-year-old. “I met her in a bar and tried to pick her up,” he laughs, “Which is kinda funny because she likes girls.”

The pair have now become good friends, and as singer-songwriters they share an aesthetic as well as a certain lyrical wit and ability to convey their lives, hopes and fears openly. While Gorman shares Barnett’s love for “wordy” artists like Lou Reed and Big Star, his songs also bear the hallmarks of classic 70s acts like Neil Young, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin and The Flying Burrito Brothers, not to mention the patron saint of singer-songwriters himself. “I love Dylan,” he says. “I think I look a fair bit like him, I’ve got the hair, the harmonica and the guitar.

Having grown up in the small Australian town of Torquay, he started playing in bands in Geelong along with King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard frontman Stu Mackenzie. “We all wanted to play like the Kinks, the Who and the Stones,” he remembers. “There was only one venue, a hotel, so we all used to go there to play music and it was this weird, crazy scene.”

Mackenzie returned to play drums on Gorman’s debut album ‘Slow Gum’, which is due out in June. Showcasing songs from the record at The Haunt during The Great Escape, Gorman’s show ran the gamut from open-hearted confessionals to indie disco floor-fillers. But for Gorman, who speaks in person with a stutter that doesn’t affect him onstage, most of his songs were simply written as therapy. “I write songs to deal with my shit,” he says. “Some people go boxing, play football or go to the gym. I just like to let go of my energy by sitting down and playing guitar – I probably should go to the gym a bit more though. My touring beer-belly is getting a little bit out of hand.”

The Great Escape 2015: Ho99o9

Not content with merely inspiring mosh pits, Ho99o9 (it’s pronounced ‘Horror’) are the sort of band who want to be down there in them. During their Great Escape set at Patterns it doesn’t take long before co-vocalist Eaddy is off the stage and in the pit, shirtless and screamin into his mic. A few days earlier, at their first ever London show at Electrowerkz, Eaddy and bandmate The OGM had begun the show in the crowd: one wearing a wedding dress, the other with a plastic bag over his head.

Not content with merely inspiring mosh pits, Ho99o9 (it’s pronounced ‘Horror’) are the sort of band who want to be down there in them. During their Great Escape set at Patterns it doesn’t take long before co-vocalist Eaddy is off the stage and in the pit, shirtless and screamin into his mic. A few days earlier, at their first ever London show at Electrowerkz, Eaddy and bandmate The OGM had begun the show in the crowd: one wearing a wedding dress, the other with a plastic bag over his head.

Although they’ve now moved to LA, Ho99o9’s shows pull together the disparate influences they witnessed growing up in New Jersey, on the outskirts of New York, where The OGM says they bonded over “girls” and going to “punk shows, rap shows and art shows.” All those elements combine in a visceral mix the pair have been honing since they first played together in 2012. “We went into it headfirst with our eyes closed,” remembers Eaddy. “We weren’t really expecting anything or trying to be a certain way.”

There’s more to them than killer lives shows. Their music – drenched in blood- and-gore imagery straight from horror films and slasher flicks – stands up to repeated playback. “Our music is diverse,” says Eaddy. “A lot of it is built for the live show, but a lot of it you can take home, listen to it, vibe to it, drive to it, bash your head against the wall to it or just chill and smoke a doob to it.”

There’s a new EP due on June 8 before they return to the UK in August to play Reading and Leeds. If their Great Escape debut is anything to go by, they’ll no doubt end up as one of the most talked about bands of the summer. “We want to make a statement with our presence,” says Eaddy. “It’s a powerful force. It’s like Mike Tyson entering the ring. You’re thinking: ‘This motherfucker’s about to do some damage.’ It’s heavyweight title shit.”

Catfish & The Bottlemen: Van McCann on setting off “a little bomb in the music industry”

At first, he thinks it must have started raining. It’s August 2014, moments before Catfish And The Bottlemen are due onstage at Reading Festival, and Van McCann can see crowds of people running towards the tent, pushing their way forward to squeeze inside. Then he looks outside and sees there’s nothing but sunshine. “That’s when I knew it was real,” he says. “I thought they were just coming in because it was pissing it down, but it was still sunny. When we went on they knew all the songs. Our album wasn’t even out yet. It was mental.”

After tearing through their set, Van walked offstage and noticed the band’s management team were crying tears of joy. “I think everyone was kind of taken aback,” he says. “Playing T In The Park and then Reading and Leeds last year were real game-changers for us. Before that we’d been playing 50-100 capacity venues, and they’d been crazy – but then at the festivals it was just as crazy and there were 4,000 more people.”

A lot has happened since then. In the past six months, the band released debut album ‘The Balcony’, which duly hit the Top 10 and went gold. Meanwhile, their live reputation has grown to the point that they sold out two nights at London’s 5,000-capacity O2 Academy Brixton this November – within nine minutes of tickets going on sale. “That’s 10,000 tickets,” marvels Van. “Could we have sold 20,000 in 20 minutes? You’re on your way to stadiums then, aren’t you?”

Cover story for NME, 16 May 2015. Continue reading.

Everything Everything on new album ‘Get To Heaven’: “All these songs are absolutely killer”

Fat White Family’s Lias Saudi on gentrification and the disappearance of squat culture

“We’ve opened Pandora’s Box”

For the past year, Carl Barât has been launching his new band The Jackals while cranking The Libertines back into action. As of last week, it’s full steam ahead with the latter – Barât signed off Jackals duties on April 16 at London’s Scala, where the band were joined by a full brass section. After that it was back home to pack. “I’ve been waking up in the morning with Libertines lyrics in my head, hurriedly getting the typewriter out, then figuring out brass arrangements for the Jackals in the evening,” said Barât, before the show. “But I’m off to Thailand tomorrow for a month’s recording. This is the album. The big push.”

For the past year, Carl Barât has been launching his new band The Jackals while cranking The Libertines back into action. As of last week, it’s full steam ahead with the latter – Barât signed off Jackals duties on April 16 at London’s Scala, where the band were joined by a full brass section. After that it was back home to pack. “I’ve been waking up in the morning with Libertines lyrics in my head, hurriedly getting the typewriter out, then figuring out brass arrangements for the Jackals in the evening,” said Barât, before the show. “But I’m off to Thailand tomorrow for a month’s recording. This is the album. The big push.”

Joining the band in Southeast Asia (Pete Doherty’s just returned from Laos on what Barât described as “a visa run”) is the album’s newly appointed producer. After much speculation about who’d take up the mantle (Noel? Clash man and ‘Up The Bracket’ producer Mick Jones?) their choice is surprising – it’s Jake Gosling, who was previously Grammy-nominated for his work on Ed Sheeran’s mega-hit ‘The A Team’. Barât explains: “We had wish lists flying back and forth, from the [John] Leckies through to the [Paul] Epworths and Stephen Street. What it boiled down to was that we wanted to try something a bit new. We wanted someone who is just getting their thing going, rather than someone who is just going to put us through their machine. This isn’t a heritage band making a heritage album.”

Barât also confirmed that while the new record has been written in full, the band intend to keep writing creating during the process. “The feeling’s great,” he said. “We’ve been sparking. The pistons are all firing. I’m genuinely excited, and can’t wait to get this stuff out there. It’s nice to be back in that position. We’ve all been waiting to write this record for ages.”

Although he concedes the band have something to live up to, Barât insists they are not overly concerned with the past. “We try not to think too much about out legacy,” he said. “The energy that we had and used in our music hasn’t left us. We’re still as driven and full of wonder about the world, but now we have more experiences and more to say to each other, and to the world. It’s exciting. We need to get it done now. Now we’ve started this process we’ve opened Pandora’s Box, so we’ve at least got to have a drink with these demons.”

It means The Jackals, who Barât recruited via open auditions in a London pub, are back on the shelf for a short while. “It’s dawned on the band that we’re at the sunset of this cycle now,” said Barât. “We’ve been in the trenches together, but I think now they’re going to knuckle down and figure out what it is they’ve got to say and what I can bring to it. As much as I prize this thing with The Jackals, and doing the hard work touring on a shoestring, with The Libertines we’ve done all that and more. It’s been a tumultuous ride. When I’m back in a room with those boys, that’s all that exists. We have history, and songs that we can just lie back and fall into. If I lie back in this band I’ll just fall into the drumkit…”

Originally published in NME, 25 April 2015.

Between Rock And A Hard Place

If ever a band was equally loved and loathed it is Mumford & Sons. Their first two albums have sold over three million copies each and they’ve cracked America in a way that no British band has managed since Coldplay. Their brand of earnest folk rock has taken them to The White House, where they played for Obama, and Glastonbury, where they headlined in 2013. Yet the same sincerity that’s won them legions of fans has brought them an equal number of detractors. They are gentlemen of the middle of the road: wildly successful, but deeply uncool.

If ever a band was equally loved and loathed it is Mumford & Sons. Their first two albums have sold over three million copies each and they’ve cracked America in a way that no British band has managed since Coldplay. Their brand of earnest folk rock has taken them to The White House, where they played for Obama, and Glastonbury, where they headlined in 2013. Yet the same sincerity that’s won them legions of fans has brought them an equal number of detractors. They are gentlemen of the middle of the road: wildly successful, but deeply uncool.

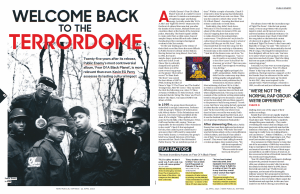

Welcome Back To The Terrordome

As Public Enemy’s ‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ turns 25 it couldn’t be more relevant. It stands as a masterpiece of righteous anger and furious energy. Lyrically, tragically, tracks like ‘911 Is A Joke’ and ‘Fight The Power’ returned to the forefront of the cultural discourse last year after the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown at the hands of the American police. Musically, The Bomb Squad’s ability to create order from a white noise chaos of sampled loops, stolen riffs and radio chatter foreshadowed the coming technological overload of the 21st Century.

Yet the year leading up to the release of their third record had been the most difficult in Public Enemy’s already storied history. Having formed on Long Island, New York in 1982, the band’s sample-heavy production style and Chuck D and Flavor Flav’s politically-charged lyrics quickly made them one of the most revered rap groups on the planet. Their debut record ‘Yo! Bum Rush The Show’ was named the best album of 1987 by NME critics, beating the likes of Prince’s ‘Sign O’ The Times’ and The Smiths’ ‘Strangeways, Here We Come’. They repeated the trick the following year, when ‘It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back’, which included hits like ‘Bring The Noise’ and ‘Don’t Believe The Hype’, was named NME’s best album of 1988 ahead of records by REM, Morrissey and The Pogues.

Yet in 1989, the group found themselves embroiled in an ugly controversy. Professor Griff, the group’s ‘Minister of Information’, told Melody Maker that: “If the Palestinians took up arms, went into Israel and killed all the Jews, it’d be alright.” When grilled on this point by David Mills, of the Washington Times, Griff went further still, saying: “Jews are responsible for the majority of the wickedness in the world.” Chuck D first apologised for him, then called a press conference to announce that Griff would be suspended from Public Enemy. A week later, the group’s label boss, Russell Simmons of Def Jam, announced that Chuck D had disbanded Public Enemy “for an indefinite period of time”.

Within a couple of months, Chuck D returned to deny that the group had disbanded, but by now a shadow had been cast over the band. This was the context in which they wrote ‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ – knowing that their next release could make or break them.

Predictably, they didn’t back down. ‘Welcome To The Terrordome’, released ahead of the album in January 1990, saw Chuck D rapping lines that many took to relate directly to the anti-Semitism controversy: “Crucifixion ain’t no fiction/So-called chosen frozen/Apology made to whoever pleases/Still they got me like Jesus”. Later, Chuck said that he wrote the song over the course of a two day road trip to Allentown, Pennsylvania in the midst of the controversy. “I just let all the drama come out of me,” he told Billboard magazine. “‘I got so much trouble on my mind/I refuse to lose/Here’s your ticket/hear the drummer get wicked”. That was some true stuff. I just dropped everything I was feeling.”

Although rightly apologetic for Griff’s anti-Semitism, Public Enemy didn’t let the controversy stop them writing angrily and graphically about the social problems they’d witnessed in American culture. Most withering of all was ‘911 Is A Joke’, in which a scornful Flavor Flav highlights differing police response times in black and white neighbourhoods. The song is a classic example of the symbiotic writing relationship between the group’s two frontmen: Chuck D wrote the incendiary title and then passed it to his partner to build a song around. “It took a year, but Flavor was saying he had a personal incident that he could relate that to,” Chuck said. “At the end of the year when it was time for him to record he was ready. Keith [Shocklee, Bomb Squad] had the track, and it was the funkiest track I heard. It reminded me of uptempo Parliament/Funkadelic.”

After skewering the police, Public Enemy then reset their sights and took aim at capitalism as a whole. ‘Who Stole The Soul?’ was their furious attack on the commodification of black culture, and Chuck D has called it one of their “most meaningful performance records”. They weren’t just calling for words or token apologies: they wanted action. “We talk about reparations,” he remembered later. Whoever stole the soul has to pay the price.”

The album closes with the incendiary, insurrectionary rage of ‘Fight The Power’. Like the best protest music, it is a song written with a specific political target in mind, which has now become a universal anthem of political resistance. On a recent European tour, Chuck D told NME that the song grows stronger as it takes on the historical context of wherever it is played. “In Belgium, we dedicated ‘Fight The Power’ to the Democratic Republic of Congo,” he said. “The memory of Patrice Lumumba [first democratically elected prime minster of Congo, who fought for independence from Belgium] will not be in vain. You always have to be aware where you’re going to when you step into somebody’s home. That’s the thing that sets us apart as different. We’re not the normal rap group.”

Sonically, too, they were no normal group. Sprawling over 20 tracks, ‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ is hip-hop at it’s most musically ambitious. Having toured as a support act for the Beastie Boys (as referenced in the radio phone-in samples that make up ‘Incident At 66.6 FM’), they were inspired by the sample-laden ‘Paul’s Boutique’, released in 1989, to add soul and jazz influences without dialling down any of the anger of their earlier recordings.

Beastie Boys were in turn equally inspired by a band they considered their heroes. Adam Yauch later said: “Public Enemy completely changed the game, musically. No one was just putting straight-out noise and atonal synthesizers into hip-hop, mixing elements of James Brown and Miles Davis; no one in hip-hop had ever been this hard, and perhaps no one has since. They made everything else sound clean and happy, and the power of the music perfectly matched the intention of the lyrics. They were also the first rap group to really focus on making albums – you can listen to ‘…Nation of Millions…’ or ‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ from beginning to end. They aren’t just random songs tossed together.”

It’s a testament to Public Enemy’s vision as songwriters that out of the controversy of uncertainty of 1989 they were able to forge a masterpiece of both social commentary and musical innovation. Echoes of their anger and ambition can still be heard, 25 years on, in the verses and activism of Kendrick Lamar, Run The Jewels and Young Fathers.

‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ continues to challenge and provoke listeners, precisely because it doesn’t offer easy solutions to society’s ills. Reviewing the album for Melody Maker in 1990, Simon Reynolds summed it up: “Public Enemy are important, not because of the thoroughly dubious ‘answers’ they propound in interview, but because of the angry questions that seethe in their music, in the very fabric of their sound; the bewilderment and rage that, in this case, have made for one hell of strong, scary album.”

Wytches’ Brew

Hyena

When you’re a grunge band in the sleepy Shropshire town of Telford, devoid of indie clubs and rock bars, you have to make your own fun. The first night frontman Jake Ball, bassist Josh Taylor, guitarist Dom Farley and drummer Reuben Gwilliam spent together as a four-piece, they overindulged, as teenagers do, on their parents’ red wine. “It’s become known as ‘the night of the black sick’,” says Jake. “Somebody was sick on my face. That was the grossest moment of my life.”

When you’re a grunge band in the sleepy Shropshire town of Telford, devoid of indie clubs and rock bars, you have to make your own fun. The first night frontman Jake Ball, bassist Josh Taylor, guitarist Dom Farley and drummer Reuben Gwilliam spent together as a four-piece, they overindulged, as teenagers do, on their parents’ red wine. “It’s become known as ‘the night of the black sick’,” says Jake. “Somebody was sick on my face. That was the grossest moment of my life.”

Full piece in NME, 11 April 2015.

In The Name Of The Fathers

Last October, Young Fathers upset the bookies by winning the Mercury Prize with their debut LP ‘Dead’. The trio were quickly sketched in the tabloid press as a publicity-shy Scottish hip-hop group making difficult, experimental music, not least because they refused to speak to any right-leaning newspapers – like The Sun, Daily Express, Daily Mail, Daily Star, The Times and The Telegraph. For the Edinburgh trio, it wasn’t a case of shunning the limelight, but a clear and conscious political decision. “We’ve had that rule for years,” explains producer and vocalist Graham ‘G’ Hastings. “There are certain publications that are cross-the-line evil to us because of their Islamophobia and homophobia.”

Last October, Young Fathers upset the bookies by winning the Mercury Prize with their debut LP ‘Dead’. The trio were quickly sketched in the tabloid press as a publicity-shy Scottish hip-hop group making difficult, experimental music, not least because they refused to speak to any right-leaning newspapers – like The Sun, Daily Express, Daily Mail, Daily Star, The Times and The Telegraph. For the Edinburgh trio, it wasn’t a case of shunning the limelight, but a clear and conscious political decision. “We’ve had that rule for years,” explains producer and vocalist Graham ‘G’ Hastings. “There are certain publications that are cross-the-line evil to us because of their Islamophobia and homophobia.”

Two Sun journalists discussed their refusal to speak to the paper on Twitter. “Young Fathers sound, er, pretentious utter cocks. Fuck ’em and eat ’em,” one wrote. The other replied: “Absolute pricks… Never getting in The Sun again.”

“That’s the kind of cunts you’re dealing with,” says G. “We thought there were other bands around who wouldn’t talk to them, but that whole way of thinking has been deleted. If you cause a fuss about something, like talking about Palestine, people say: ‘Oh what are you starting that for?’ That’s why we want as many people as possible to know we exist. Even if they hate us, it still changes their perception of what’s real in the world. We’re not saying that they should take all the shite songs off the radio. We’re just asking for a bit of contrast.”

Young Fathers’ cosmic, gorgeously arranged new album, ‘White Men Are Black Men Too’, is purpose-built to provoke that kind of debate. “We’re asking: ‘What is a white man?’ ‘What is a black man?’ ‘What is a Muslim man?’ ‘Are women sexualised?’” says G. “The title is a multifaceted, metaphorical statement. We live in a world that’s not equal. We all know that. The question is how do we start a conversation where people will feel that they can be open enough to express themselves?”

The question comes back to the essence of the band, too, who bristle at being pigeonholed as a Scottish hip-hop group. The truth is that Young Fathers are a global pop band. To call them Scottish makes as little sense as calling your iPhone Chinese – the parts may have been assembled there, but the ideas, design and components come from all over the planet. Young Fathers’ bearded singer Alloysious Massaquoi was born in Liberia. Dreadlocked co-vocalist Kayus Bankole’s parents are Nigerian and raised him partly in the USA. G was born and raised in Edinburgh, and it’s G who’s chiefly responsible for the beats, which blend everything from Afropop to soul to gospel to blues to indie. There are stickers on vinyl copies of ‘White Men…’ which direct shops to ‘File under Rock and Pop’.

“We keep having to tell people that we’re pop,” says G. He’s sat with his bandmates between piles of instruments and books in their manager Tim Brinkhurst’s tiny basement studio in Leith, in the north of Edinburgh. “We didn’t want to be considered a leftfield, strange group, and if you say that the album’s hip-hop you’re just fucking lying. It’s just not fucking true. That’s just a tag that we’re stuck with because of how we look. It’s borderline racist. Unfortunately eye always beats ear. People go on what they see first.”

Alloysious, who goes by Ally, nods: “If we were all white and making the kind of music we do I don’t think we’d get these comparisons.”

Young Fathers see themselves as the antidote to the lazy media pigeonholing that says all black musicians must be rappers and all white musicians play guitar. Kayus, the quietest of the three, explains it in more personal terms. “I have a little nephew and he’s really into music,” he says, “but if people are constantly portrayed as belonging to a certain bracket of music then he’s going to think that’s how things should be. It’s easy for the media to put things into narrow categories, but that confines people. That’s what we’re getting at with the title of this album.”

Young Fathers have been making music together since the age of 14, since meeting at a club night at Edinburgh’s Bongo Club that played hip-hop, bashment and dancehall. It’s there that Kayus was introduced to British rappers like Roots Manuva and Blak Twang, while Alloysious remembers discovering Sean Paul and “amazing pop songs”.

G just remembers having his mind blown. “It was the sort of place I couldn’t go to with my mates who I grew up with,” he says. He was given a dead arm by his old friends when they found out he’d visited it. Their idea of a night out was drinking hooch and having a fight at a youth centre disco. No dancing allowed.

“When I got into The Bongo Club and saw these guys and everybody else dancing I thought: ‘Fucking hell! People are dancing in public!’” says G. “I joined in, like it was nothing, but inside I was thinking: ‘THIS IS FUCKING AMAZING!’ It was so liberating to be able to express yourself. Nobody was pointing at you and going: ‘Who do you think you are? You think you’re special?’ It was something that had been missing from my life.”

After the music had finished and they could hear each other speak, G invited Ally and Kayus to come and visit his mum and dad’s house. “They’d come round and I’d make a beat on this software that I bought for £10,” he explains. “I put it onto a CD, then you’d press record on the karaoke machine. We’d put the mic up in the cupboard, and then crowd round it. We’d try and do it in an arrangement. We were literally pushing each other, because you only had one take. I think that ethos has stuck with us.”

The band are all now 27, and in the intervening years have held down all manner of jobs to support their musical ambition. That makes them a rare working class success story in 2015. “Middle class bands are the most content, tasteless cunts around,” says G. “They’re so comfy that understanding anything with a bit of bite or grit about it seems like rocking the boat. They’re taking up space. They don’t realise they have a duty to show society a broad spectrum of stuff. Instead all their mates, who should have sold fucking insurance, start a band. Working class bands have been eradicated.”

‘Young Men Are Black Men Too’ was recorded mainly in Berlin, although even with their Mercury Prize winnings (£20,000) Young Fathers had no intention of hiring a flash studio. Instead they just drove their usual gear over to Germany and set up in a similar basement to the one where they made ‘Dead’.

The record draws together the issues of race, power and class that pervade the band’s conversation today. Take ‘Sirens’, which deals with police violence over a driving rhythm. “We say “the police are on cocaine” because when you see videos online of policemen shooting unarmed men, it’s like they’re on coke,” says G. “They can do whatever they want and get away with it.”

Perhaps the strangest song on the record is ‘Nest’, which was commissioned for a Nestlé advert. Nestlé have been the subject of a long-running boycott due to their aggressive marketing of baby milk powder in the developing world, which has been linked to the spread of disease and increased malnutrition. When the band were approached their first reaction was to tell the multinational to, in G’s words, “go fuck themselves.” Instead, the band decided to accept the commission and planned to spend their fee on a high-profile anti-Nestlé billboard campaign. Even the song they wrote was trolling: “We made them a song which says ‘baby’ about 100 times in it. All the lyrics are about ‘Feed me mama’ and ‘Food for the village’,” explains G. “We sent it to them and they said they fucking loved it!” In the end it fell through, but Young Fathers kept the song.

Undoubtedly, satirising multinationals and asking difficult questions about race places Young Fathers outside of what’s currently considered mainstream pop music – but that’s pop music’s problem, not theirs. They’re on a mission to make pop a more interesting place. That means having to put up with being misunderstood.

“It’s too much work for the media to say that people are complicated,” says Ally. “It’s simpler to just pass judgement and place people in a box. The people in charge don’t want new ideas or change because they don’t know what it spells. It could be the end of their reign. That means TV and radio doesn’t want change. If they were putting out interesting ideas, it would make people realise that change is possible. That’s what we’ve got to do.”

The Van who would be King

Cigarette paper between his fingers, Van McCann is sat in the smoking room at the back of Catfish & The Bottlemen’s tourbus. It’s parked outside Schubas Tavern in Chicago, a 200-capacity room where the band are due onstage in less than an hour.

“I don’t know what to do,” he croaks.

Sat across from him is Catfish’s sound guy, Mike Woodhouse. “Your voice is fucked,” says Mike, “so the way I see it, you have three options. Option one: sing as normal. From what you’re saying, that’s not an option. Option two: get the audience to help you. Get them to sing like you did that night in Leeds. Option three: pull the gig, but…”

Van cuts him off. “We’re not pulling the gig.” Catfish & The Bottlemen have never pulled a gig. “People have paid their hard-earned money and they’ve already been waiting outside for hours,” Van says, gesturing to the snow piled up outside. “It’s fucking freezing out there.”

On their current American tour Van has been up at 9am every day to do live sessions for radio and local TV before the band’s evening gigs. He says that’s why his 22-year old voice currently sounds like a waste disposal pipe. He’s tried all sorts to save it. He’s tried not drinking. He’s even tried not smoking, and Van smokes likes it’s a dying art. Nothing made any difference.

“Our label says we have to do sessions if we want to be the biggest band in the world,” he says, “but it frustrates me that the competition winners at the session this morning are going to get a better show than the fans tonight. I’m only in this band to write songs and sing. It frustrates me when I can’t do it.”

The rest of the band and management once again propose cancelling the gig, even at this late hour. Van won’t hear of it. If Catfish & The Bottlemen have made it this far – two sold-out nights at O2 Academy Brixton, a Top 10 UK debut album in ‘The Balcony’, appearing on Letterman – it’s because of Van’s work ethic, about which he’s endearingly earnest. Catfish have been gigging hard since 2009. This is their second US tour and it too is completely sold out, but Van refuses to let anyone treat it like some kind of victory lap. If they want to keep reaching new heights, they have to be responsible about it. No slacking or hard partying. Schubas Tavern is a rung on the ladder to playing big shows: Van wants Oasis at Knebworth, The Stone Roses at Spike Island.

“I remember going to see Oasis at Heaton Park,” he says. “It was like everyone was going to the core of the earth. It was like Jesus was back. A couple of lads from Burnage did that? That looks good to me.”

The first thing Van McCann says when he gets onstage is: “I need you tonight, Chicago. My voice has gone completely so I need you as much as you can.” The band launch into opener ‘Rango’, which tilts at the stadium rock of recent Kings Of Leon songs, and Van starts thrashing around as he plays, as if hoping to make up for his lack of voice through sheer physical exertion.

The first thing Van McCann says when he gets onstage is: “I need you tonight, Chicago. My voice has gone completely so I need you as much as you can.” The band launch into opener ‘Rango’, which tilts at the stadium rock of recent Kings Of Leon songs, and Van starts thrashing around as he plays, as if hoping to make up for his lack of voice through sheer physical exertion.

“Thank you,” he rasps afterwards, then launches into an explanation that’s near enough word-for-word what he just said to Mike and the band in the bus: “I’m sorry my voice sounds so rough. I want you to know we don’t go out and get fucked up before shows. We’ve had to play sessions every morning. We love playing shows. We take this seriously. We’re professional. We’ve never pulled a show, because we’re prepared. I’m really sorry I’m not 100 per cent…”

They make it through the single ‘Pacifer’ unscathed, but Van isn’t done apologising. “I’m only here because I can sing,” he says. “I feel awful. If any of you want your money back afterwards you can have it. Or I’ll buy you a beer. I promise you I’ll buy the whole place a beer…”

A voice from the crowd cuts him off: “Shut up and sing!”

“You sound great!”

“We love you!”

They tear through ‘Fallout’ at full pace, and afterwards Van just grins. “Shit. Did I promise you all beers? I’ve just done the maths in my head. There’s a lot of you in here. Is this an 18-plus gig? So you’re all old enough to drink? Shit. I didn’t say anything about getting your money back, did I?”

The crowd laugh and shout for him to go on, but on ‘26’ his voice starts to drop out, and by the next track, the slower-paced ‘Business’, he sounds awful. The band’s tour manager runs onto the stage and puts his arms around Van’s shoulders and asks if he wants to pull the gig there and then, but Van won’t leave unless he’s dragged off.

He’s got to play the next song, because it’s ‘Kathleen’ and that’s the big radio hit. It’s the one the American fans all heard first. The one they played on the Late Show With David Letterman. The one that finds the sweet spot between The Strokes and The Cribs. Impossibly, something about ‘Kathleen’ seems to rejuvenate his voice. By the end of the song he’s full of confidence again, and signals for the other three members to leave the stage so he can play the introspective ‘Homesick’ on his own. Accompanied by just his guitar, his voice is now totally exposed and yet somehow healed. The band come back on and they roar through a couple more songs. Then, before the howling closer ‘Tyrants’, the tour manager reappears. He tells the room the band have put enough money behind the bar to buy everyone in the venue a pint.

The crowd look at each other. “Fuck,” someone says. “He wasn’t kidding!”

After the show, the band are back in the tourbus for just 13 brief minutes. Van and his best mate and guitar tech Larry shut themselves in the back room for a smoke, their post-gig decompression ritual, then open the doors and jump out into the snow to meet the fans clustered outside.

After the show, the band are back in the tourbus for just 13 brief minutes. Van and his best mate and guitar tech Larry shut themselves in the back room for a smoke, their post-gig decompression ritual, then open the doors and jump out into the snow to meet the fans clustered outside.

“We were going to invite them in and make them a brew,” says Van, “but imagine what people would think if they saw some picture of a young girl posing with us on our tourbus.”

So instead they stand around outside for an hour, even as the temperature drops down below minus 10. They separate off, and three concentric circles of fans form: one around bassist Benji Blakeway and drummer Bob Hall, one around guitarist Johnny ‘Bondy’ Bond, and the biggest around Van. A girl hugs him and says, “You changed my life!”

A 21-year-old guy called Nicholas tries to force a fistful of dollars into Van’s hand. “I just played the House Of Blues a couple of weeks ago with my band and I had bronchitis,” he explains afterwards. “I know how hard it is to go onstage and sing your heart out. When he said he was going to buy everyone in the venue a drink I got goosebumps from my toes to my fucking head. They just put on the best show I’ve ever seen, because it was so real. It’s humble, and it’s honest. The lyrics mean something to everyone. It’s not the overproduced bullshit that you usually hear on the radio. When he sings about being drunk and horny… I’ve been there. We’ve all been there.”

Only when absolutely everyone has got their selfies do Catfish climb back onto the bus. Van heads back to his smoking room, leaving the rest of the band to hang out at the front. At the end of last year Van told NME that the band aren’t really mates. After so long on the road, is that still true?

Only when absolutely everyone has got their selfies do Catfish climb back onto the bus. Van heads back to his smoking room, leaving the rest of the band to hang out at the front. At the end of last year Van told NME that the band aren’t really mates. After so long on the road, is that still true?

“I think we’re like brothers now. We get on,” says Bondy. He laughs, and continues: “Although saying that, I fight with my brother all the time.”

“There’s a family spirit,” says Benji, nodding.

Van re-emerges. After spending so much of the night worrying about his voice, he wants to think about something else. Talk turns to their next album, which he wrote months ago but first played to the band last night.

“It’s more widescreen,” says Van. “We needed to open our eyes a little bit. The album we’ve got is good, but it’s an 18-year-old boy trying to get out of a small town. When I listen to the first album now, it sounds angry. That was us trying to break out and get somewhere, and now we’re opening up and going, ‘Christ, we’re in America! This is class!’ We want to go to stadiums and play simple rock’n’roll songs. Put your girlfriend on your shoulders and your arm round your best mate. Dads can take their kids, like my dad used to take me. They’re still songs about normal life, but it’s less about John in Manchester and more about Manchester, y’know what I mean?”

The band head back into the venue to hit the bar. Van prefers to chill out on the bus. He hasn’t thought about anything other than Catfish & The Bottlemen for six years. “I’ve tried to slow it down because I realised I wasn’t enjoying it,” he says. “All the lads would be laughing and having a joke, but I’d be coming of stage thinking, ‘Fuck, I missed that note.’”

The idea is that it’ll all be worth it in the long run. Van has put every penny he’s ever earned from royalties into a separate bank account. “I’ve never touched it,” he says, “even if I wanted £40 to go to the pub. I’ve kept it all and when I have a kid I’m going to give it to them. That means every single song I’ve ever wrote will mean something to somebody. I want to be the best dad and the best husband, like my dad was to me.”

That’s why Van keeps writing songs. He wasn’t supposed to start writing that new album until April. Instead, he finished it while they were still recording the last one. Then he wrote 20 more songs. His friends in bands told him he should take advantage of his record label and get them to fly him to LA, so he hatched a plan to keep the new record a secret until April, then feign writer’s block and get a free holiday. He couldn’t do it. He shrugs. “I couldn’t hold it in.”

He loves being on tour in America, but he misses Britain. “I love pound coins,” he says, “and pasties.” Mostly he misses his “shitty cottage” in Chester, where he can write songs, play FIFA and smoke in the kitchen. That’s why, after he has eventually joined his bandmates for a few drinks, he tells them he won’t be going on to the next bar with them. Instead, he goes back to the bus with Larry, and they smoke and rewatch Austin Powers until Larry falls asleep. Then Van picks up his guitar, and he writes another song.

Brandon Flowers: In bloom

Brandon Flowers, wearing a black leather jacket and grasping a mug of green tea, is stood in the centre of a mixing studio in West London unable to keep still as he listens back to some of the final mixes for his second solo album,

He nods his head to the calypso-influenced beat of ‘Still Want You’ and grins as we hear his backing singers come crashing in. “Nuclear distress, I still want you,” they sing. “Climate change and death, I still want you.”

The subject matter may be apocalyptic, but Flowers knows exactly where he wants these songs to end up. “I want to be on the radio,” he says. “I’ve never been ashamed to say that.”

The Killers frontman is putting the final touches to his new record, which will be called ‘The Desired Effect’, ahead of its release this spring. It’s currently being mixed at Assault & Battery studio in West London by Alan Moulder, who’s been working with Flowers since the first Killers album ‘Hot Fuss’ back in 2003.

A lot has changed since then, and Flowers knows that the radio is a very different place to the one where ‘Mr Brightside’ found a home. “I can’t believe where radio has gone,” he says. “It seems to be such a weird world now. Where I once seemed to fit in, now I’m seen as a little different. I used to be considered mainstream but now I’m almost avant-garde or artrock compared to what’s on the radio.”

His plan for ‘The Desired Effect’ was to make a grown-up pop record with singles that can get played on Radio One while also carrying some weight and meaning for his long-term fans whose lives, like his, have changed over the last decade. “I’m 33 years old and I have three sons, I’ve got to try to commit to myself and not embarrass myself,” he says. “A lot of these songs could be about a man and his wife. I’m coming up on 10 years of marriage, and it’s not a cakewalk.”

Flowers took his cues from his heroes: Genesis’ Peter Gabriel, The Police’s Sting and The Eagles’ Don Henley. He says they showed him how to mature away from the bands that made their names: “I think if you look at those people, they weren’t just catering to little kids. I think adults like pop music too, and we shouldn’t be – I’m speaking for all of us – we shouldn’t be listening to a lot of that music that we’re listening to! There has always been pop music but it can speak to you too, you know? I think we’re walking a line on my new record, and hopefully we’ve found a place where there’s sophistication to it but it also feels accessible.”

Having first emerged in the wake of bands like The Strokes and Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Flowers says that he’s been listening with interest to the solo records put out by his peers, like Karen O. He laughs off the suggestion that he could ever make an album as abrasive as Julian Casablancas’ recent record with The Voidz. “I don’t know if I have that in me,” he says. “It’s like Bowie doing ‘Tin Machine’ or something like that. I just can’t… I’m too much of a pop tart.”

One contemporary record he does admire is The War On Drugs’ ‘Lost In The Dream’, although he has one problem with Adam Granduciel’s work. “I’m with everybody else on the War On Drugs train,” he says, “but I just don’t know what the hell he’s saying. I just want to turn up the vocals. The vocal melodies are great, and I love what’s happening, but I just want to be able to hear the words. I love a song that I can sing along to.”

‘The Desired Effect’ will be the follow-up to Flowers’ 2010 debut solo album ‘Flamingo’. Many critics at the time noted that it sounded a lot like a Killers record, while NME’s review argued that it was “more that The Killers’ albums sounded like Brandon Flowers solo albums, with a bit of indie guitar on top.”

This time round, Flowers wanted to make a conscious effort to explore new territory. To that end he recruited producer Ariel Rechtshaid, who made his name working with the likes of Vampire Weekend and Haim. “I’m so much a part of that Killers sound,” Flowers says, “so for me to move away from it I had to give Ariel some freedom, a little bit more slack on the rope. A lot of times it worked, and when it didn’t I was able to have a strong enough hold on things to pull the rope and get it where I need to get it.”