Images

Russell Brand: “We might be witnessing the end of democracy”

Russell Brand has been many things in his 41 years: stand-up comedian, heroin addict, movie star, Andrew-Sachs-offending national disgrace, reality TV host and three-time winner of The Sun’s ‘Shagger of the Year’, to name but six. And just when it looked like he was set to spend the rest of his days fopping around Hollywood as the token English eccentric, he recast himself as a real-life revolutionary.

In October 2013, Brand used a Newsnight interview to call for “a socialist egalitarian system based on the massive redistribution of wealth, heavy taxation of corporations and massive responsibility for energy companies and any companies exploiting the environment”. It was a far cry from making knob gags on a Big Brother spin-off, but it struck a chord with a public who at the time could only tell the difference between the three major political parties by looking at what colour tie their leader had on. Brand threw himself into activism, writing a book called Revolution, launching his YouTube channel The Trews and getting involved in the successful campaign to save the New Era housing estate in Hackney from redevelopment.

The media, however, largely focused on just one aspect of the original interview: the fact he’d told Jeremy Paxman that he didn’t think people should vote. Then, on the eve of the 2015 election, Brand changed his mind and urged people to vote for Labour’s Ed Miliband – who promptly lost resoundingly, and resigned.

In the wake of the election, Brand retreated from public view. He enrolled in a degree while the tabloids mocked his decision to move to a £3.3m house near Henley-on-Thames with his fiancée Laura Gallacher, who last year gave birth to a daughter they gave the deliberately un-celebrified name Mabel. Having licked his wounds, Brand is resurrecting himself with a stand-up tour, Re:Birth, and a new show on Radio X. We meet him in the luxurious gardens of Danesfield House, a fancy hotel near his home that’s so decidedly un-insurrectionist that George Clooney had his wedding after-party here. He’s watching his “recalcitrant hound”, a German Shepherd named Bear, lollop through the gardens. The dog, he says, has “self-control issues… I don’t know where he’s picked that up from.”

While he can’t resist that knowing joke at his own expense, Brand in person now cuts a calm, sage figure. Wearing a Trews T-shirt and gym gear, hair tied up in a bun, beard flecked with grey, he’s more Zen yoga enthusiast than marauding sex pirate. He may be less vocal with his righteous ire, but he still believes, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, that society need not be so venal. He even recently filmed himself registering to vote for the first time, meaning Britain’s most notorious non-voter could be about to cast his first ballot. Which raises the question…

Cover story for NME, 12 May 2017.

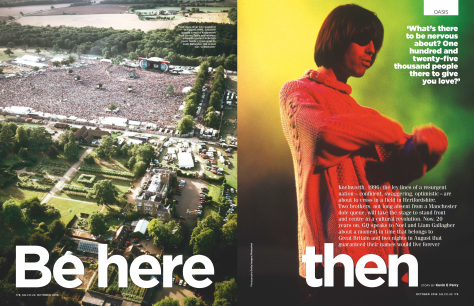

Be Here Then

Just after 9pm on Sunday 11 August 1996, Noel Gallagher stepped on stage in front of 125,000 people for the second night running, jabbed his index finger at them and bellowed:

‘This is history. Right here. Right now. This is history!

“I thought this was Knebworth,” deadpanned brother Liam, standing front and centre. “What are you on about? ‘Ah, we’re all going to History for the weekend to watch Oasis.’ It’s not on the map, our kid…”

Both brothers were, for once, right. Oasis at Knebworth was history in the making. Those two nights in a muddy field near Stevenage were the high-water mark not just for their band but for a wave of British culture that transformed the country at the end of the last century. For better or for worse, the energy of a whole generation was coming to a head.

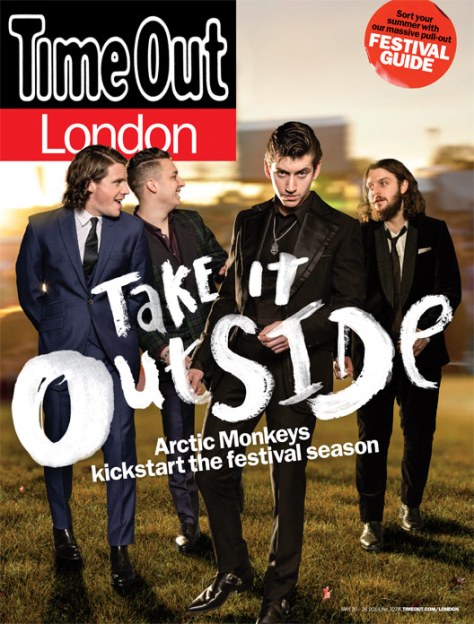

Monkeying Around

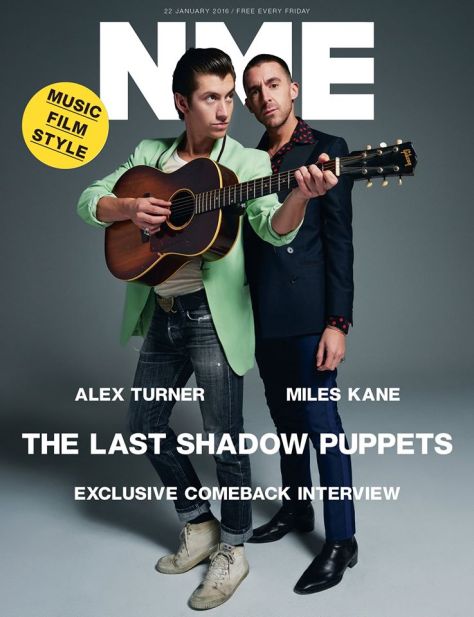

Maybe it’s because they get sick of living in each other’s filth, maybe it’s because of ‘creative differences’, or maybe it’s just because of all the drugs, but people in bands tend to end up loathing one another. But this story is quite the opposite. This is the story of two best friends who are magnetically drawn to making music together.

Maybe it’s because they get sick of living in each other’s filth, maybe it’s because of ‘creative differences’, or maybe it’s just because of all the drugs, but people in bands tend to end up loathing one another. But this story is quite the opposite. This is the story of two best friends who are magnetically drawn to making music together.

“It’s like watching footage of an explosion in reverse,” says Alex Turner. “It’s like John Lennon meets… Paul.”

So much for the age of the understatement. Alex and his Last Shadow Puppets bandmate Miles Kane are in no mood for modesty as they announce their second record, ‘Everything You’ve Come To Expect’, the follow-up to 2008’s ‘The Age Of The Understatement’.

Sitting together in Miles’ Los Angeles apartment, they’re chattering more than the two baby parrots in the cage next to them – a Christmas present from Kane’s girlfriend. They spark off each other like a comedy double act: howling at in-jokes, finishing each other’s sentences, slipping into pitch-perfect Lennon and McCartney voices.

King Of The Swingers

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

Right now he’s enjoying a rare month off. After we order coffee he tells me he’s been back at his place in east London, and that he spent the previous evening dusting off his CD collection. ‘I pulled out “The Songs of Leonard Cohen” and it still had a sticker on it. £14.99!’

Money well spent, I suggest. ‘Totally,’ he agrees. ‘Fucking “Suzanne”: what a song! I don’t have an Instagram account, but if I did I’d have grammed it, saying exactly that: “Money well spent.”’

It must be nice for him to be home, enjoying the simple pleasures of rummaging through old albums? ‘I’m not even sure where home is,’ Turner sighs. ‘Probably Terminal 5. There is a strange sense of calm about arriving back at Heathrow.’

He’s spent a lot of time in the air these last eight years. The Arctic Monkeys’ record-breaking debut ‘Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not’ launched Turner, drummer Matt Helders and guitarist Jamie Cook into the stratosphere almost overnight in 2006, with fourth member Nick O’Malley joining to replace original bassist Andy Nicholson soon after. Since then the gang of schoolmates have established themselves as Britain’s biggest contemporary rock ’n’ roll band. Last year’s heavy, sultry and tremendous ‘AM’ (their fifth album) topped the charts in nine countries and set them up for a pair of huge shows in Finsbury Park this week.

Some of the fans flocking to see them will be teenagers too young to remember the band as Yorkshire urchins, trackie bottoms tucked into their socks. There are others, however, who remember it all too well: critics who’ve accused the Arctics’ frontman of now pretending to be something he’s not. At the outset Turner wrote songs about drinking and dancing and falling out of taxis, and described those nights just the way you and your mates would, if only you were blessed with a sharper turn of phrase. Now Turner spends much of the year in LA, dates a model and dresses like a screen idol – somewhere between James Dean and Marlon Brando in ‘The Wild One’. Has he been blinded by the bright lights of Stateside success? Whatever people say about Alex Turner, who is he now?

Not a man who takes himself entirely seriously, it turns out. ‘I wish I could be that guy,’ he says, when I ask him about his International Rock Star persona. He tells me he’s happiest when he’s writing, plucking new songs out of the ether. What’s the hardest part of his job? ‘Probably the same thing,’ he deadpans, in that muttering, sub-Elvis drawl he’s cultivated. He’s taking the piss out of himself. He’s too self-aware, probably too Northern, to believe his own smooth rhetoric. ‘I wish I could be the guy who says those sort of lines,’ he says. ‘I catch myself too quick.’This February, at The BRIT Awards, that self-awareness landed him in the eye of a tabloid storm. Collecting the first of the band’s two awards, for Best British Album and Best British Group, Turner made a now notorious speech about how ‘rock ’n’ roll seems like it’s faded away sometimes, but it will never die’.

He was accused of arrogance (as if that’s such a sin in a rock star) but Turner maintains that the celebration of his genre needed voicing. ‘I was trying to present an option in an entertaining way,’ he says. ‘In a room like that, where we were the only guitar band, it’s easy to start feeling like an emissary for rock ’n’ roll. If that’s what people were talking about after the Brits rather than a nipple slipping out, that’s a good thing. In a way, maybe it is a nipple slipping out.’

Raised on a diet of Britpop, Turner can’t have imagined being in Britain’s biggest rock band and having to make that sort of clarion call. I ask him if he ever feels like the Arctics are an Oasis without a Blur to lock horns with. He laughs. ‘It would be really arrogant to say that there’s just us. There are others but there are very few bands on the radio. It doesn’t have to be that way. I think that’s where that speech was coming from.’

Turner is the sort of man who chooses his words carefully, occasionally retrieving a comb from a pocket so that he can attend to his quiff and buy a few more seconds of thought. Award shows don’t come naturally. ‘As perverse as this may sound, I don’t really enjoy being the centre of attention,’ he says. ‘It’s all right during a show, because I’d argue it’s the song or the performance that’s the centre of attention. It’s not like me opening my birthday presents in front of everybody. I’m not a big fan of that. I think making a speech falls into that category. It’s like getting a trophy for a race that you didn’t really know you were running. There’s a twisted side to it. I can come off as ungrateful, but fuck it. That’s just the truth.’

That subtle sleight-of-hand to keep a part of himself out of the limelight may also explain the bequiffed, leather-clad character he’s created, although he’s quick to dismiss the idea that the band are keeping it any less ‘real’ than when they started out. ‘Tracksuits are as much of a uniform as a gold sparkly jacket,’ he says. ‘We made a decision to keep dressing like that at the start. It’s as contrived as anything else. It’s a sort of theatre.’

So don’t expect him to dig out a pair of shorts for Finsbury Park (‘Unless I’m within splashing distance of water I won’t be caught dead in them, as a rule’). He’s happy that audiences seem more excited to hear tunes from ‘AM’ than old stuff (‘Still got it!’), but he’s self-effacing about what’s made this record such a success. ‘I think the production is what makes people move. The words are just me blabbing on, the usual shit.’

Our time’s up but Turner’s in no hurry. We sit and chat about books, and as befits the sharpest lyric writer of his generation he’s the sort of reader who can quote his favourite novels. He’s a fan of Conrad and Hemingway, but above all Nabokov. He recites a line about internalised anger from ‘Despair’: ‘I continued to stir my tea long after it had done all it could with the milk.’

After an hour or so, it’s time for a smoke. As we leave the coffee shop the manager stops us. He’s noticed the turned heads. ‘Excuse me,’ he asks me, ‘are you the singer in a band?’ Alex Turner laughs out loud. He doesn’t need his ego massaging. He’s a bona fide rock ’n’ roll star.

I’m In It

Ellesmere Port is an industrial town in the north west of England, 13 miles south of Liverpool. There’s not a lot going on around here. It used to be that young people would go and get jobs at the oil refinery or the chemical plant. Some of them got jobs in the car factories that secrete the Vauxhall Astras that flow along the town’s major arteries as if in convoy. But times are changing. Nowadays kids leaving school are more likely to end up working in the big retail park that’s grown up on the other side of town, shifting Ellesmere Port’s centre of gravity geographically as well as economically. The kids that can get out move to the cities and forget all about Ellesmere Port, telling their new friends they’re from the nearby well-heeled city of Chester instead.

Ellesmere Port is an industrial town in the north west of England, 13 miles south of Liverpool. There’s not a lot going on around here. It used to be that young people would go and get jobs at the oil refinery or the chemical plant. Some of them got jobs in the car factories that secrete the Vauxhall Astras that flow along the town’s major arteries as if in convoy. But times are changing. Nowadays kids leaving school are more likely to end up working in the big retail park that’s grown up on the other side of town, shifting Ellesmere Port’s centre of gravity geographically as well as economically. The kids that can get out move to the cities and forget all about Ellesmere Port, telling their new friends they’re from the nearby well-heeled city of Chester instead.

Josh Leary is different.

Omar Souleyman: “I bring a message of love”

A man named Rizan Sa’id is alone on the stage of a converted underground car park in Hackney, his face impassive as he begins to play a fast-paced reworking of an old Arabic folk tune on a Yamaha keyboard and a big Korg synthesiser. It’s 10:30pm on the closing Sunday of the inaugural London Electronic Arts Festival, which goes some way to explaining the odd industrial surroundings – although they’re no doubt stranger to Rizan, who’s more used to playing this distinctly Middle Eastern music at Syrian weddings.

A man named Rizan Sa’id is alone on the stage of a converted underground car park in Hackney, his face impassive as he begins to play a fast-paced reworking of an old Arabic folk tune on a Yamaha keyboard and a big Korg synthesiser. It’s 10:30pm on the closing Sunday of the inaugural London Electronic Arts Festival, which goes some way to explaining the odd industrial surroundings – although they’re no doubt stranger to Rizan, who’s more used to playing this distinctly Middle Eastern music at Syrian weddings.

A powerful, disembodied voice fills the room. His song builds and builds before the singer himself emerges from backstage. He’s wearing an ankle-length khaki thawb, a distinctive keffiyeh headscarf known as a shemagh, and a pair of dark Antonio Miro shades which he never, ever removes on account of an eye injury sustained aged five. The crowd, already driven into the beginnings of a frenzy by the music, set about losing their shit at the appearance of Omar Souleyman. The trace of a smile plays across his lips. “Thank you”, he says, as the song finishes, one of only a handful of things he’ll say in English. Later, with the aid of an interpreter, he tells me he always likes to appear on stage already singing. “It’s good because in a way it surprises the audience,” he says. “I like surprises.”

It’s lucky Omar likes surprises, because he never expected to find himself playing festivals all over the globe, or to release a Four Tet-produced album on Domino Records, where he counts Arctic Monkeys, Franz Ferdinand and Animal Collective among his label mates. Omar, now 45, has lived for his entire life in Tel Amir, a small town on the outskirts of Ras Al Ayn, near Syria’s border with Turkey. He has been singing for his own entertainment since the age of 7, but he spent his teenage years working odd jobs in agriculture or construction to make ends meet. “I’d take any sort of labour,” he tells me over black coffee the morning after his show, “If it would help me eke out a living.”

Sometimes though, when he got lucky, people would let him sing at their weddings. “They used to allow me to sing for five or ten minutes,” he explains. “I took it as a form of practice, to help me refine my style.” By 1994, when Omar was 26, he was starting to find himself in demand as a wedding singer. The demand grew and grew. Nowadays, people ask him to sing for two or three hours.

He recorded all of his wedding performances, sometimes playing back-to-back events in a single day, and then distributed the tapes. This vast library of live material brought him fame across Syria and throughout neighbouring countries like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Eventually his tapes came to the attention of Seattle label Sublime Frequencies, who began to release his music in the West. Omar found himself with a new fan base that he’d never expected, and with it his music took on a new significance. “When I perform now in Europe and North America I bring a message of love and a message of friendship,” he explains, “And it’s also a message which introduces Arabic music to Western audiences. I’m really very proud of this.”

When he did make the journey west, he took it in his stride. “I’m self-confident, in a way, because I worked for this. I worked really hard for this,” he says. “Even though initially I wasn’t expecting to perform in Europe or America, by the time I came here I was very self-confident about myself.” The same goes for recording his new record in New York with Kieran Hebden, better known as Four Tet. “It was quite smooth,” says Omar. “We’ve recorded in different studios before, so working with Kieran was no problem.”

Omar sings, as he speaks, in Arabic, but his music and the poetry of his lyrics resonate with audiences even if they don’t understand a word. Songs like ‘Wenu Wenu’, the title track of his new album, are built around repeated phrases. In English, the chorus translates as: “Where is he? Where is he? The one I loved – where is he?”, which is a diacope, a rhetorical flourish that Shakespeare loved, which is why his characters are always saying things like: “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” or “My horse, my horse, my kingdom for a horse”. “There’s always a language barrier,” says Omar, “but my lyrics are very simple. I’ve noticed that when I sing ‘Wenu Wenu’, Western audiences will sing it with me.”

Many of the cultural differences between the Middle East and East London hipsters aren’t as wide as you might assume. While there’s no drinking at Syrian weddings – because of the presence of parents and grandparents – Omar does drink himself socially. Just never before a show. “Sometimes those who drink excessively may pass out when they’re onstage,” he points out. “This is a grave mistake for any artist who is appreciated by the people.” I hope Pete Doherty is taking notes.

Today, off duty, Omar has switched his headscarf and robe for a simple white baseball cap and a brown bomber jacket. “I wear my traditional clothes all the time back home,” he explains, “but here I don’t want to be very distinct from everybody else except for when I’m onstage. While I’m walking in the street I don’t want to be the focus of everybody’s attention,” He laughs. “It would be as if I’m going to do a show in the street.”

After he leaves London, Omar will be pulling his shemagh back on and heading home. Despite the brutal civil war currently devastating Syria, he says the situation in his own relatively remote village has stabilised. “There are no problems,” he says. “It’s isolated and I can go back whenever I want. As a singer I keep a distance from all these disputes.”

He’ll be on the road again before too long. “My ambition is to take part in the biggest music festivals in the world,” he says. The message of love that he brings to everyone: men, women, Syrians, Westerners, even hipsters, is too important not to spread. Omar’s music lets us hear something from Syria above the sound of bombs dropping on the news. He lets us hear humanity. “If you look at the general situation in the world,” he says, “A few radicals have inserted these bad ideas about the East in the West. This is something I completely disagree with. I’m trying to correct it with my music. I’m working against hate. Whenever I sing to Western audiences I really enjoy the way we interact: singing, clapping and dancing. I really love them.”

Originally published in NME, 30 November 2013.

“We’re the living embodiment of the belief that you can do whatever you want.”

If you only know The Flaming Lips as electric-hued purveyors of highly-polished psychedelic pop and hosts of the world’s most euphoric live shows, their new album might be a jolt. Aptly titled ‘The Terror’, it’s a dark and abrasive record that stares into the abyss and yet, somehow, still manages to find some beauty amid the fear and dread. Truth is, this band have always been more comfortable than most dealing with the big existential questions, from when they started out as a mind-bending punk band recording songs about ‘Jesus Shootin’ Heroin’ right through to smuggling a blunt and jarring reminder of humanity’s fragile mortality into their most universally adored anthem. Over glasses of single malt at a well-appointed hotel in London’s Clerkenwell, Wayne Coyne gets heavy on everything from the mysteries of free will, reinventing The Flaming Lips and the importance of getting fucked up now and again.

The Flaming Lips are a hard band to pin down. I first discovered you when ‘Yoshimi…’ came out, but then for Christmas my dad bought me your early box-set ‘Finally The Punk Rockers Are Taking Acid’.

Hahaha! Well, he’s ruined it for you then! You thought we were those people who made ‘Yoshimi…’, and then that record ruined it for you!

I was like: ‘What the fuck is this shit?’ It blew my mind.

‘Yoshimi…’ is so refined. We made it on purpose to use commercial music as an experiment. We were listening to fucking Nelly Furtado and shit like Madonna. I mean we loved it but we were using it as a palette. It’s so well made. It’s a trick because we sound like we really know what we’re doing and the truth is we don’t know what we’re doing.

The abrasiveness of ‘The Terror’ seems to hark back to The Flaming Lips’ earlier, more experimental material: songs like ‘Jesus Shooting Heroin’.

Bizarre songs like that, yeah. When we were young we had no guide. You kind of just make what you can. Sometimes you wish that you knew more about production, but it is what it is. We’ve made 16 records now and it does lead you into this world which helps you understand about sound and how you can use it to evoke certain things. The main thing you learn about music is that if something’s good, don’t fuck it up. The really good things that happen in music are collisions. In the beginning, we took punk rock in the same sense as John Lydon said it: anarchy. In music and art, do whatever the fuck you want, just fucking do it. It quickly turned into punk rock being a particular look and sound. That isn’t what we thought of it. We thought it was just: “You’re fucking free.” When we proclaimed ourselves The Flaming Lips we asked ourselves: “How long will this last?” We thought it would last six months and then we’d be back at our restaurant jobs. We thought that would be the end of the story but the fucking story never ended. You keep thinking that someone is gonna knock on the door: “Flaming Lips, we know it’s all bullshit, it’s over”. “Okay you caught me, I surrender” but nobody has yet. We’re the living, breathing, somewhat successful embodiment of this retarded belief that you can do whatever you want and we really do live by that.

How did writing ‘The Terror’ compare to previous albums?

Sometimes you feel compelled to follow a sound. When we were making ‘The Soft Bulletin’ we didn’t think about making it, we just followed a sound. That really means rejecting all these other sounds. You might not know what you like, but you know what you hate. I think ‘The Terror’, in a sense, is the same thing. I don’t think people will look at like ‘The Soft Bulletin’, with whatever that means to people, but I think for us it feels like we’ve self-destructed again, not in the same way but with the same intensity. The minute we said: ‘This is how we’re gonna be as a band forever’, absolutely the next second we were completely different and utterly changed. I think we’re onto probably the third phase, the third version, of The Flaming Lips.

What gives you ‘The Terror’?

When you’re young, you feel that it’s you that’s saying: “I want this”, “I don’t want that” or “I’m rejecting that”. It feels as though it’s something that we decide from the front of our minds. For me, when it comes to ‘The Terror’ the shocker line is: “We don’t control the controls.” The intense way that we love is not something that we have a say over. It’s a part of our subconscious life that probably comes from our parents or from whatever our bullshit DNA has made us. It’s like the reason you’re tall and have hair and the reason the other guy is short and doesn’t. We don’t decide, dude! Something in us gets to decide. When you’re young you can say: “My eyes were decided by my DNA but the music I listen to isn’t.” As you get older, it starts to seem like you don’t really know how much of anything you get to decide. That’s ‘The Terror’. ‘The Terror’ is that it appears everything is normal and alright but inside you is a fear that says: ‘I don’t know.’ That’s why this music is full of anxiety and feels stressful. It feels depressing but it’s kind of triumphant. You know something now, but the thing you know is disturbing.

‘The Terror’ also seems to speak about mortality and the existential terror that comes from our knowledge of it. That’s the ultimate thing you can’t control. It reminds me of ‘Aubade’ by Philip Larkin, do you know it?

Yeah, I’ve read it, it’s cool. As far as control goes, well, you can kill yourself. That would give you some control, although even that is probably something that is innate in you. It’s probably part of your personality, that’s the twist on all of it. You don’t know, of everything you reach for, how much is you wanting it and how much you’ve been pre-ordained to want it, but loving something helps us not feel so alone. That’s part of it too, we’re trapped in the isolation of our own minds. Fear can make part of you say that you’ll live in the middle. “I won’t lust for this and I won’t care about that.” That’s another form of ‘The Terror’. Who wants to fucking live like that? You can’t live in this fucking nothing grey zone where nothing is gained and nothing is lost. You have to surrender. All the great things require that you give in. You can’t even have an orgasm if you’re too fucking scared and hold back. It’s the same in the moment where you’re conscious that you’re falling asleep. It’s God. It’s everything. That’s the most beautiful thing that happens to you, but you have to surrender.

Even a song like ‘Do You Realize??’ contains seeds of terror within it.

It does. I mean, it’s a very optimistic world with some terrible seeds in the middle, whereas ‘The Terror’ is the just the seeds themselves. I don’t think the success of ‘Do You Realize??’ is because we’re clever or because we’re such good songwriters. There are almost a million songs that play that exact same thing. That chord change is used so often because it works. Whatever kind of mind it is listening to it, if you like The Beatles you like these chord changes. It plays on you in a way that is optimistic and it appears to be telling a story that you already know which is a good story. Then I start singing these words and then right at the time when you’re at your most comforted in the song, I tell you this horrible line, that “Everyone you know, someday, will die,” and it’s almost as if you go: “It’s okay,” and you take it in because that’s what the music and everything has done. That isn’t because we’re smart or anything, that’s just dumb fucking luck that that momentum or whatever allowed that to happen. I understand that’s how it is for most really great artists. It’s just a dumb luck combination and I see that now. At the time I didn’t see that. I remember asking Steven: “What do you think of this?” and when I went to that line he said: “Dude, that’s a Wayne classic right there, man. You got it!” But even then you don’t have any idea that people are gonna play it at funerals or that it’s gonna take on this other meaning.

When you look back at your life, what advice would you have given your younger self?

I was very serious back then about making myself be an artist. All my brothers and older sister, they’re great people but they’ve all been on some level or another a drug addict. I was very serious. I didn’t want to indulge in everything because I’d be as vulnerable as them and end up addicted to the same drugs. It’s very difficult to keep pursuing music and art when life become too much of a calamity. However, if I could I would probably tell myself: “Wayne, for two weeks you get to be as serious and work as hard as you fucking can, but on this night, get fucked up.” I think it would’ve served me well because I would’ve had some relief. I think that’s the reason I do drugs and stuff now. I understand that I’m broken in the way that I will take things very seriously and I will work too hard and be too intense, but then I’ll get fucked up and not care that much. When I come back to myself, some of the things I was so serious about won’t worry me. It allows you, if you’re lucky, some perspective.

Sometimes you need to take a holiday from your own head, don’t you?

Yeah, and back then I didn’t value that, I thought these lazy assholes, all they wanna do is get drunk. I wanna make music I wanna make art but, you know, I’d tell myself to have fun.

Mick Jagger hints at future Rolling Stones tour

Mick Jagger has suggested that The Rolling Stones’ 50th anniversary shows this year will not be their last, and has said he’d love to take the band to Australia.

Mick Jagger has suggested that The Rolling Stones’ 50th anniversary shows this year will not be their last, and has said he’d love to take the band to Australia.

Asked on the red carpet at the premiere of new Stones documentary Crossfire Hurricane earlier this evening (October 18) if they would be heading Down Under, Jagger said: “Not this week! We’re going to go and rehearse this week but I hope to go to Australia. I haven’t been there in years.”