Losing your job is rarely pleasant, but simultaneously losing your employment, your cultural traditions and a way of life that supports whole communities is a worse redundancy package than most. For hundreds of thousands of Indian silk weavers, this is a reality which has seen the jobless forced into such desperate measures as selling their blood or even their own children to make ends meet. Death from starvation is common, although many take their own lives first.

Losing your job is rarely pleasant, but simultaneously losing your employment, your cultural traditions and a way of life that supports whole communities is a worse redundancy package than most. For hundreds of thousands of Indian silk weavers, this is a reality which has seen the jobless forced into such desperate measures as selling their blood or even their own children to make ends meet. Death from starvation is common, although many take their own lives first.

It is only just dawn in Varanasi, one of Hinduism’s holiest cities, but the street corners and marketplaces are already teeming with people. Among them is Bhaiya Maurya, but he has not come here to admire the ancient temples that rise from the banks of the Ganges. He has come here, like everyone else, to look for work – any work. Over the next hour, trucks will come and collect labourers. If Bhaiya is chosen he’ll make 75 rupees today, less than £1, and he will consider himself lucky. Two days out of three his luck is out and he’ll go home empty-handed. Across the globe, recession is making countries fear the spectre of mass unemployment. Here in Uttar Pradesh, India’s northern and most populous state, there are more than three times as many mouths to feed as in the UK. The numbers out of work are staggering and the threads that bind them together are made of silk.

Waiting at home in the village of Damodarpur 15 km from Varanasi is Bhaiya’s father, Hari. He is a master weaver who in the past decade has seen falling demand, rising costs and increased foreign competition decimate the silk trade. At its peak, it employed a million people in this area. Now, it employs less than half that number. As Hari explains: “A few years ago, everyone in my village was engaged in hand-weaving. Now, most people are unemployed. If everyone had work, then the village would develop automatically. First we need jobs, and only then will come safe water, electricity and roads.”

Waiting at home in the village of Damodarpur 15 km from Varanasi is Bhaiya’s father, Hari. He is a master weaver who in the past decade has seen falling demand, rising costs and increased foreign competition decimate the silk trade. At its peak, it employed a million people in this area. Now, it employs less than half that number. As Hari explains: “A few years ago, everyone in my village was engaged in hand-weaving. Now, most people are unemployed. If everyone had work, then the village would develop automatically. First we need jobs, and only then will come safe water, electricity and roads.”

There is debate over whether the jobs they so urgently need can come from the labour-intensive hand-weaving sector, as they have in the past. The Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh might have been thinking of the silk weavers of Varanasi when he told the G20 recently that he would resist the “inevitable pressures” for protectionism caused by “low growth and high unemployment”. The struggles of this industry are the familiar problems that increased mechanisation and globalisation can bring. Traditional hand-woven saris simply cannot compete on cost with machine-made garments from China.

Falling demand is also a symptom of cultural change. Fashions are changing across the subcontinent and Indian communities worldwide. Young girls are less likely than their mothers to wear saris. When they do, they want lighter, tighter designs, not the heavy, gold-and-silver-embroidered Banarasi sari of antiquity.

However, this weight of history and tradition may turn out to be the hand-weavers’ greatest asset. The Banarasi sari is famous throughout India and traditionally every Hindu bride will wear one on her wedding day. Weavers such as Hari are the only ones skilled to make it authentically, having passed the knowledge down from generation to generation. Ashok Kapoor, a trader who has worked to help preserve hand-weaving, sums up his concerns bluntly. “I don’t care about the starving weavers,” he tells me. “I care that the art is dying.”

Four and a half thousand miles away, in Whitechapel, London, there is evidence of what British politicians might call “green shoots of recovery”. The Banarasi sari remains a marketable brand. Imported saris sell for about £250, but even within India it can be difficult to be sure that what is sold as a Banarasi sari has actually originated in Varanasi. That is now changing. Realising that substandard imitations were damaging their reputation, and sales, the weavers have organised a co-operative, Banaras Bunkar Samiti (BBS). They now negotiate with traders as a group and, with support from the development agency Find Your Feet, they have managed to persuade the government to introduce a patent for Varanasi’s saris. This protects their product in the same way as champagne or Darjeeling tea. KP Verma, the assistant director of the state government’s handloom department assures me that this will have a transformative effect on the lives of the weavers, but Hari is wary. He is quick to point out that any success the patent has will rely on demand from relatively wealthy consumers who are prepared to follow the lead of Banarasi fans such as Bollywood’s Aishwarya Rai and pay a premium for luxury. Traders and exporters such as Maqbool Hasan concede that while there is still demand for genuine Banarasi silk from Indian elites, many buyers, including the large export markets of America and Europe, care only about price.

The only thing that will revive the hand-weaving industry is co-operation. As well as lobbying the government, BBS have also formed microcredit groups to help the weavers back on their feet. A loan from the co-operative enabled Hari to reopen the loom he calls “the symbol of my pride”. It is now the only one in his village, where once there were 200, but it is a start. With help from Bhaiya’s younger brother, Krishna, Hari has diversified from saris into a wider range of garments and home furnishings targeted at India’s growing middle class. Meanwhile another son, Raju, was supported by a BBS loan to learn computerised embroidery. He is now one of the few villagers to earn a salary.

The only thing that will revive the hand-weaving industry is co-operation. As well as lobbying the government, BBS have also formed microcredit groups to help the weavers back on their feet. A loan from the co-operative enabled Hari to reopen the loom he calls “the symbol of my pride”. It is now the only one in his village, where once there were 200, but it is a start. With help from Bhaiya’s younger brother, Krishna, Hari has diversified from saris into a wider range of garments and home furnishings targeted at India’s growing middle class. Meanwhile another son, Raju, was supported by a BBS loan to learn computerised embroidery. He is now one of the few villagers to earn a salary.

However, at a meeting of the microcredit group there is acknowledgement that silk is now too fragile a trade to support the weight of this community on its own. Former weavers are encouraged to embrace an entrepreneurial spirit. Recent loans have been used to buy buffaloes, which are popular for their milk, or to establish shops and develop agriculture. The treasurer, Nirmala, tells me: “Each house used to have looms and every house used to weave, but now we would die if we stuck to that profession only.”

Having started out with little and lost much, the first task for these communities is creating new opportunities. Hari is a man of quiet dignity. He does not ask for charity. He wants only the opportunity to work himself and his family out of their situation.

As he says: “The most important thing in the definition of development is jobs. Work is essential for each and every hand.”

Originally published in The Guardian.

Read more about a former factory owner here: ‘Ghost in the factory’.

Read more about a local women’s microcredit group here: ‘Finance for the future’.

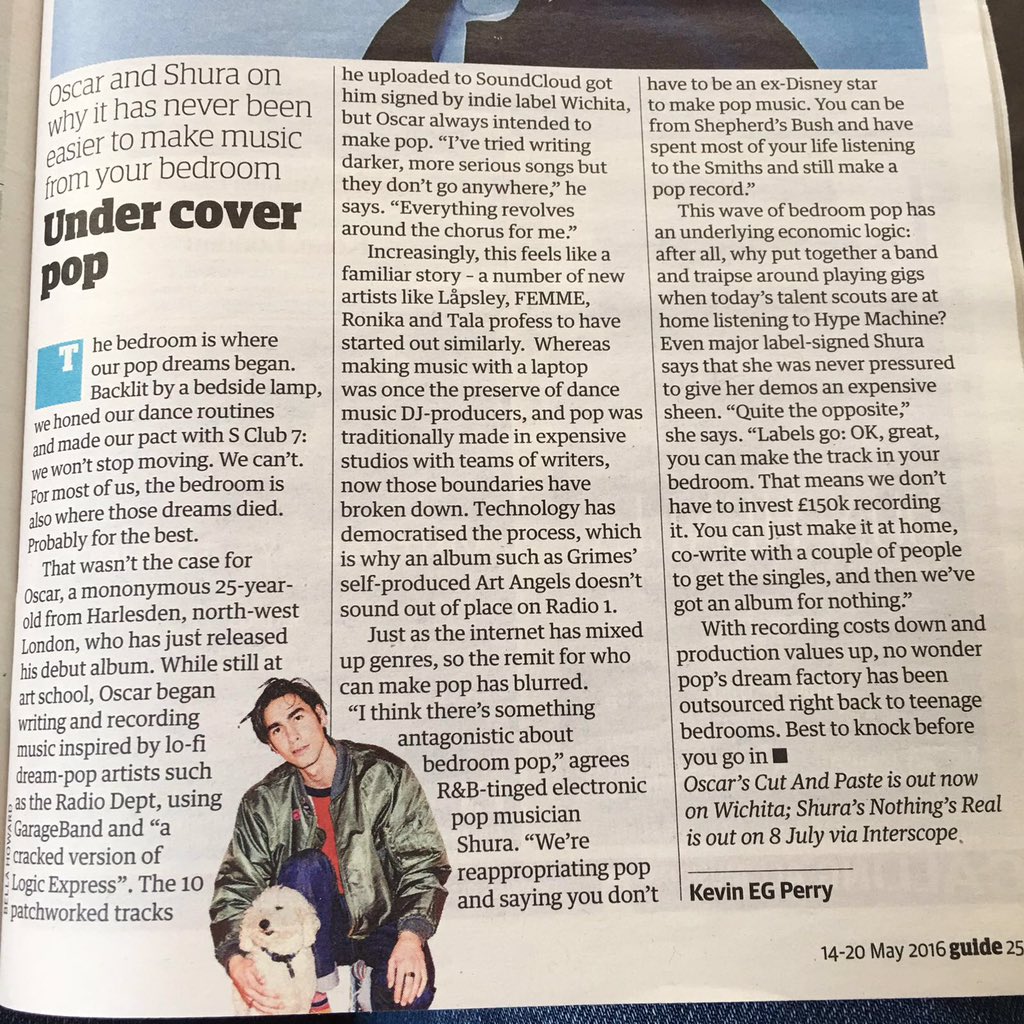

T

T

Founded in 1887 by a Finnish sea captain named Gustave Niebaum, Inglenook is a sprawling 1,680-acre winery known as “the Queen of the Napa Valley”. The estate contains 280 acres of vineyards, a Queen Anne-style Victorian mansion and a magnificent stone-and-iron chateau, all of which combine to create a refined northern Californian ambience that is about as far away as it’s possible to imagine from being in the shit in Vietnam.

Founded in 1887 by a Finnish sea captain named Gustave Niebaum, Inglenook is a sprawling 1,680-acre winery known as “the Queen of the Napa Valley”. The estate contains 280 acres of vineyards, a Queen Anne-style Victorian mansion and a magnificent stone-and-iron chateau, all of which combine to create a refined northern Californian ambience that is about as far away as it’s possible to imagine from being in the shit in Vietnam.

No matter who is behind the decks come 7am, Warung Beach Club always has the same headline act. The main room of the 2,500-capacity temple to dance music on the Brazilian coast faces east towards the south Atlantic, which means God herself does the lighting. “When the sun comes up, it’s magical,” says club founder Gustavo Conti, standing on a terrace overlooking the beach. “That’s because nature is magical, and we’re here in it.”

No matter who is behind the decks come 7am, Warung Beach Club always has the same headline act. The main room of the 2,500-capacity temple to dance music on the Brazilian coast faces east towards the south Atlantic, which means God herself does the lighting. “When the sun comes up, it’s magical,” says club founder Gustavo Conti, standing on a terrace overlooking the beach. “That’s because nature is magical, and we’re here in it.”

Jordan Cardy, a 21-year-old who goes by the name of Rat Boy, inspires the sort of fevered devotion that often seems to follow those with his initials. His fans start arriving six hours early for the launch of his debut album, Scum, gathering in the cold and damp, graffiti-covered tunnel beneath London’s Waterloo station. One of the first to arrive is 16-year-old Saskia, who deftly explains Rat Boy’s appeal. “He sings about being poor quite a lot, and I find that really relatable,” she says. “He’s singing about things everyone our age is feeling.”

Jordan Cardy, a 21-year-old who goes by the name of Rat Boy, inspires the sort of fevered devotion that often seems to follow those with his initials. His fans start arriving six hours early for the launch of his debut album, Scum, gathering in the cold and damp, graffiti-covered tunnel beneath London’s Waterloo station. One of the first to arrive is 16-year-old Saskia, who deftly explains Rat Boy’s appeal. “He sings about being poor quite a lot, and I find that really relatable,” she says. “He’s singing about things everyone our age is feeling.”

I

I

It’s almost a surprise that Wayne Coyne doesn’t roll up to our interview in his giant hamster ball. The Flaming Lips frontman is so defined in his Wayne Coyne-ness that, waiting around, it’s hard not to picture him as he appears onstage: an intergalactic pirate smothered with fake blood and confetti, flanked by dancing pandas, his boulder-sized fists raised aloft to shoot green lasers into the sky. This is a man whose life is such a carnival of oddness that he’ll sometimes forget he’s carrying a solid gold hand grenade, which didn’t go over well when he took it through customs at Oklahoma City’s airport back in 2012. When he wanders into the lounge of his Clerkenwell hotel engulfed in a baggy hoodie, he can’t help but seem down to earth measured against his reputation. Despite the glitter in his snowy ringlets and the glue-on plastic diamonds studded around his right eye, he’s human after all.

It’s almost a surprise that Wayne Coyne doesn’t roll up to our interview in his giant hamster ball. The Flaming Lips frontman is so defined in his Wayne Coyne-ness that, waiting around, it’s hard not to picture him as he appears onstage: an intergalactic pirate smothered with fake blood and confetti, flanked by dancing pandas, his boulder-sized fists raised aloft to shoot green lasers into the sky. This is a man whose life is such a carnival of oddness that he’ll sometimes forget he’s carrying a solid gold hand grenade, which didn’t go over well when he took it through customs at Oklahoma City’s airport back in 2012. When he wanders into the lounge of his Clerkenwell hotel engulfed in a baggy hoodie, he can’t help but seem down to earth measured against his reputation. Despite the glitter in his snowy ringlets and the glue-on plastic diamonds studded around his right eye, he’s human after all.

What with all the time-consuming acid trips and having to grow your hair long, psych-rock hasn’t generally attracted a lot of people with a strong Protestant work ethic. That’s at least until bizarrely titled Melbourne seven-piece King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard gave the genre a shot in the arm and made everyone else look downright idle by releasing eight records in the last four years. Now they’ve upped the ante even further, announcing that in 2017 they’ll release no fewer than five new albums.

What with all the time-consuming acid trips and having to grow your hair long, psych-rock hasn’t generally attracted a lot of people with a strong Protestant work ethic. That’s at least until bizarrely titled Melbourne seven-piece King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard gave the genre a shot in the arm and made everyone else look downright idle by releasing eight records in the last four years. Now they’ve upped the ante even further, announcing that in 2017 they’ll release no fewer than five new albums.

For most pilgrims it is a long way to Lake of Stars festival. This year the event returned to its original site at Chintheche Inn in northern Malawi, seven hours by bus from the capital Lilongwe. Many artists come from further afield still, across Africa and Europe. Alongside them this year were groups of refugees making their own journey from Malawi’s Dzaleka camp.

For most pilgrims it is a long way to Lake of Stars festival. This year the event returned to its original site at Chintheche Inn in northern Malawi, seven hours by bus from the capital Lilongwe. Many artists come from further afield still, across Africa and Europe. Alongside them this year were groups of refugees making their own journey from Malawi’s Dzaleka camp.

I wish I’d known… not to be ‘vibey’

I wish I’d known… not to be ‘vibey’

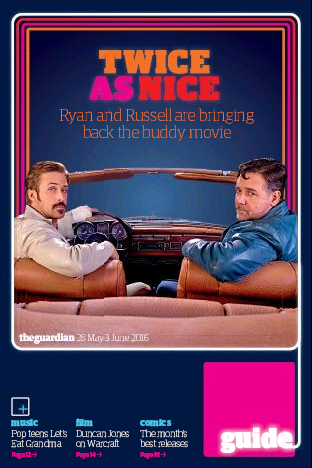

A lot of people liked Shane Black’s 2005 directorial debut, the self-referential neo-noir romp Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, but Russell Crowe wasn’t one of them. “I think it’s too aware of itself,” he says. “It feels like there’s an in-joke going on in that movie, and I don’t connect to that. It’s not funny for me if the guy thinks he’s being funny.”

A lot of people liked Shane Black’s 2005 directorial debut, the self-referential neo-noir romp Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, but Russell Crowe wasn’t one of them. “I think it’s too aware of itself,” he says. “It feels like there’s an in-joke going on in that movie, and I don’t connect to that. It’s not funny for me if the guy thinks he’s being funny.”

In the past year,

In the past year,

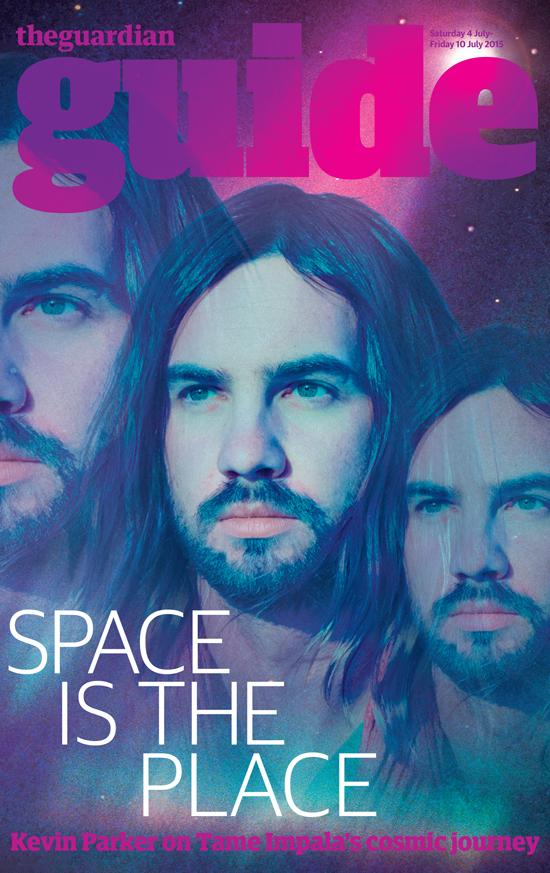

It’s a few days before Glastonbury, and Kevin Parker – the 29-year-old Australian musical polymath behind Tame Impala – is in west London rehearsing for his appearance at the festival with Mark Ronson. Somewhat extravagantly, Ronson has hired out the entirety of the Hammersmith Apollo for the week as a practice room. Presumably he can afford it, though. “Have you ever heard of a little song called Uptown Funk?” jokes Parker.

It’s a few days before Glastonbury, and Kevin Parker – the 29-year-old Australian musical polymath behind Tame Impala – is in west London rehearsing for his appearance at the festival with Mark Ronson. Somewhat extravagantly, Ronson has hired out the entirety of the Hammersmith Apollo for the week as a practice room. Presumably he can afford it, though. “Have you ever heard of a little song called Uptown Funk?” jokes Parker.

Ships, churches, car parks, roofs, drained swimming pools, bank vaults, derelict coaches… Exploding Cinema will put on a film screening just about anywhere in the UK. Well, except for actually in a cinema. It’s been 23 years since the London-based democratic collective was founded in a squatted sun tan oil factory in Brixton. Since then they’ve screened more than 1,000 films, taking in everything from French pop hits subtitled with anarchist philosophy to darkly surreal shorts. One thing remains constant: their dedication to screening everything and anything they get sent.

Ships, churches, car parks, roofs, drained swimming pools, bank vaults, derelict coaches… Exploding Cinema will put on a film screening just about anywhere in the UK. Well, except for actually in a cinema. It’s been 23 years since the London-based democratic collective was founded in a squatted sun tan oil factory in Brixton. Since then they’ve screened more than 1,000 films, taking in everything from French pop hits subtitled with anarchist philosophy to darkly surreal shorts. One thing remains constant: their dedication to screening everything and anything they get sent.

For a country of 1.25 billion people, India has never been a major stop on the international live music circuit. Sure, there’s been a smattering of heavy metal gigs and a one-off Beyoncé show in Mumbai in 2007, while Sting can always be counted on to throw in a sitar concert between yoga retreats, but low ticket prices and high production costs mean that big tours by the likes of U2 and Rihanna have traditionally bypassed the country.

For a country of 1.25 billion people, India has never been a major stop on the international live music circuit. Sure, there’s been a smattering of heavy metal gigs and a one-off Beyoncé show in Mumbai in 2007, while Sting can always be counted on to throw in a sitar concert between yoga retreats, but low ticket prices and high production costs mean that big tours by the likes of U2 and Rihanna have traditionally bypassed the country.

At first, Yung Lean’s Yoshi City video is just like any other young up-and-coming rapper’s. The teenager hangs out of a moving car surrounded by his crew. There’s a phone in his hand, a fag in his mouth. But the familiar rap tropes are scrambled into a kind of super-internet pastiche. His ride’s a sensible Smart car; his crew, sullen adolescents from Stockholm who call themselves the Sad Boys. Beside him sits not Cristal but a bright pink My Little Pony. And there’s Lean himself: a chubby-cheeked cherub, more Directioner than Chicago South Side, who deadpans about being a “lonely cloud”. “We just thought it was funny,” he says later. “I’m not really into My Little Pony, I’m not a ‘Brony’, just to clear that up.”

At first, Yung Lean’s Yoshi City video is just like any other young up-and-coming rapper’s. The teenager hangs out of a moving car surrounded by his crew. There’s a phone in his hand, a fag in his mouth. But the familiar rap tropes are scrambled into a kind of super-internet pastiche. His ride’s a sensible Smart car; his crew, sullen adolescents from Stockholm who call themselves the Sad Boys. Beside him sits not Cristal but a bright pink My Little Pony. And there’s Lean himself: a chubby-cheeked cherub, more Directioner than Chicago South Side, who deadpans about being a “lonely cloud”. “We just thought it was funny,” he says later. “I’m not really into My Little Pony, I’m not a ‘Brony’, just to clear that up.”

I’ve been in shock twice in my life. The first time was when my best friend broke his arm playing five-a-side football. It was a nasty break. The bone came through the skin and he lost a lot of blood. I helped him out of the school hall on a rush of adrenaline. It was only later, after the ambulance had gone, that I started to feel breathless and my hands shook uncontrollably.

I’ve been in shock twice in my life. The first time was when my best friend broke his arm playing five-a-side football. It was a nasty break. The bone came through the skin and he lost a lot of blood. I helped him out of the school hall on a rush of adrenaline. It was only later, after the ambulance had gone, that I started to feel breathless and my hands shook uncontrollably.

Losing your job is rarely pleasant, but simultaneously losing your employment, your cultural traditions and a way of life that supports whole communities is a worse redundancy package than most. For hundreds of thousands of Indian silk weavers, this is a reality which has seen the jobless forced into such desperate measures as selling their blood or even their own children to make ends meet. Death from starvation is common, although many take their own lives first.

Losing your job is rarely pleasant, but simultaneously losing your employment, your cultural traditions and a way of life that supports whole communities is a worse redundancy package than most. For hundreds of thousands of Indian silk weavers, this is a reality which has seen the jobless forced into such desperate measures as selling their blood or even their own children to make ends meet. Death from starvation is common, although many take their own lives first. Waiting at home in the village of Damodarpur 15 km from Varanasi is Bhaiya’s father, Hari. He is a master weaver who in the past decade has seen falling demand, rising costs and increased foreign competition decimate the silk trade. At its peak, it employed a million people in this area. Now, it employs less than half that number. As Hari explains: “A few years ago, everyone in my village was engaged in hand-weaving. Now, most people are unemployed. If everyone had work, then the village would develop automatically. First we need jobs, and only then will come safe water, electricity and roads.”

Waiting at home in the village of Damodarpur 15 km from Varanasi is Bhaiya’s father, Hari. He is a master weaver who in the past decade has seen falling demand, rising costs and increased foreign competition decimate the silk trade. At its peak, it employed a million people in this area. Now, it employs less than half that number. As Hari explains: “A few years ago, everyone in my village was engaged in hand-weaving. Now, most people are unemployed. If everyone had work, then the village would develop automatically. First we need jobs, and only then will come safe water, electricity and roads.”