Published in Uncut, Review of the Year 2024

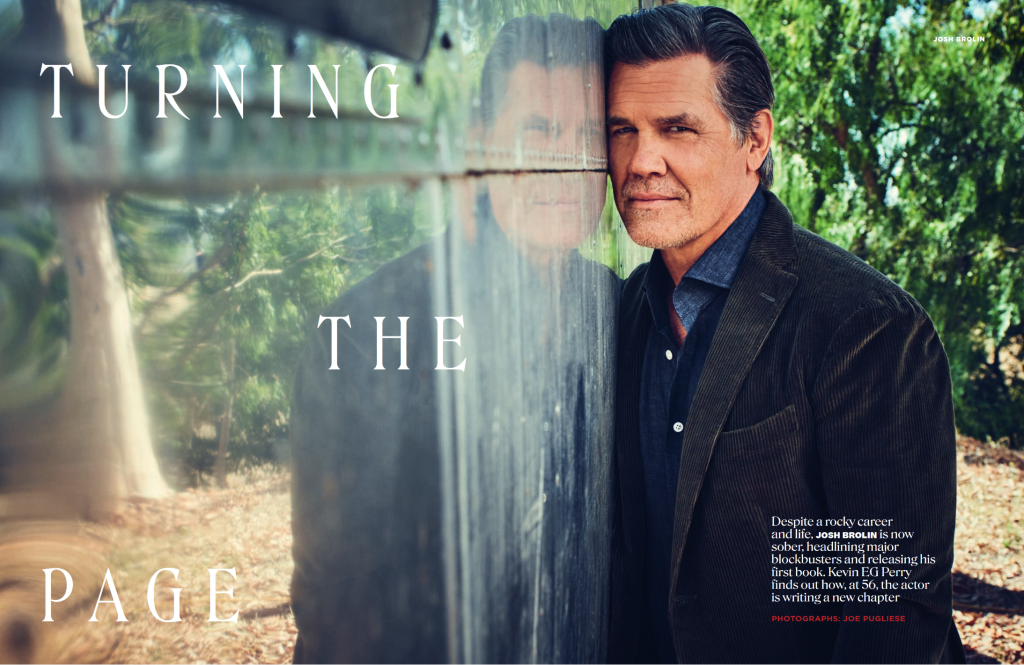

Josh Brolin slows his big black pick-up truck to a crawl as soon as he spots the injured deer on the mountain road ahead of us. He gives the wounded animal a wide berth and pulls up alongside a sheriff already on the scene, exchanging a few words of concern and expressing brotherly solidarity with the lawman’s watchful task. A moment later we pull away, continuing our winding descent from the remote Malibu film ranch where the 56-year-old has spent the morning being photographed for the cover of this month’s Vera. For the first time in the few hours we’ve spent together, Brolin falls into a contemplative silence.

The Oscar-nominated star of No Country For Old Men and Avengers: Endgame may have inherited his surname and his good looks from his TV-famous father, James Brolin, but he wasn’t born into a movie career. Rather than spending his childhood amid the glitz and sheen of Hollywood, Brolin grew up with dirt under his fingernails on a ranch outside Paso Robles, several hours north up the California coast, where his fierce and unpredictable mother Jane Cameron Agee kept a sort of menagerie.

“Whether I was birthing mountain lions, or cleaning wolf cages, or feeding 65 horses at 5:30 in the morning at eight years old… it was a pain in the ass,” Brolin tells me with a grin that breaks through his powder-white goatee. “But I look back on it now and I’m happy. Once directed properly, it gave me the ability to face fear in a very productive way… like with writing this book.”

The book in question is From Under The Truck, Brolin’s soon-to-be-published memoir that’s about as far from a clichéd celebrity autobiography as you’re ever likely to lay eyes on. He calls publishing it: “The scariest thing I’ve ever felt in my life.” It’s a raw, surprising and deeply affecting work from a man who dreamed of being a writer long before he ever stumbled his way into his father’s profession. “It’s what I’ve always loved, number one,” he tells me earnestly about writing. “I’ve never not done it every day.”

From Under The Truck throws out conventions like chronological time to skip back and forth between tales of love and loss, professional victories undone by alcoholism, childhood trauma and drug-fuelled teenage escapades. There are skittering poems, romantic vignettes and keenly-observed dialogues that read like kitchen-sink dramas. At the heart of it all there’s Jane, a hard-drinking, rabble-rousing, larger-than-life character who preached the gospel of country-and-western and raised her son to be an ass-kicker in her own image before driving drunk into a tree and dying at 55. “I had no plan to write a book. I just started writing, and then when I finished I realised I was 55,” Brolin says softly. “I went: ‘Jesus Christ, I thought my mom was old when she died.’ I thought she’d lived a good, full life. I realised she was young, super young. There was a whole other life to be lived.”

Brolin’s own life is proof of the possibility of second acts, and even further reinventions beyond that. At 13 he was dropping acid in the Santa Barbara suburb of Montecito, a member of a punk rock surf crew known as the Cito Rats, watching friends die young and assuming a similar fate awaited him. When his mother predicted he’d follow in his father’s footsteps, he pushed back hard. “I don’t know if I’ve ever told anybody this,” he says, running a hand through his salt-and-pepper hair. “At one point she said: ‘You know you’re going to be an actor.’ I had no interest in acting. Zero. I didn’t care for what my dad did. It made him go away a lot. The fluctuations in money made no sense to me. I hated that she said that. It made me hate it even more.”

Things changed when he took a high school improv class. He liked making people laugh by transforming into someone else, liked having to think on his feet. When he was kicked out of home he went to stay on his dad’s couch. “I just started going on audition after audition,” he remembers. “Maybe the Brolin name made people curious, but I also know people tried to stop me getting jobs because I was Brolin’s son. The Goonies was like the 300-and-something audition. I went back in six times because they wanted to make sure I was right for that part.” He was, and a bandanna-wearing 17-year-old Brolin made his screen debut in the much-loved adventure classic in 1985. “It was a silver platter experience,” he says. “It was all downhill after that!”

Almost before he realised it, Brolin’s promising future was behind him. He followed the The Goonies with a string of forgotten, forgettable films. “What did I do after Goonies?” Brolin asks rhetorically. “I was in the business 22 years and nobody cared.” In the book, Brolin juxtaposes his memories of Goonies with his impressions of landing the lead role in the Coen Brothers’ Oscar-winning No Country For Old Men over two decades later. “Those are the two milestones,” he explains.

The role remade his career overnight. “Before No Country I wasn’t making any money,” Brolin says matter-of-factly, explaining he took up day trading to support his two kids from his first marriage to actress Alice Adair. “I was always a numbers person, the geek in school that would ask the math teacher for extra work, so I was good at it. I realised I was watching fear and greed, and success had everything to do with discipline. I made more money trading than I’d ever made from acting up to that point.”

After No Country, he had his pick of roles and specialised in deconstructing masculine archetypes. He earned an Oscar nomination in 2009 for rendering the “pathetic” Dan White sympathetic in Gus Van Sant’s Milk, and gave vivid life to the chocolate-banana-inhaling, hippie-stomping cop “Bigfoot” Bjornsen in Paul Thomas Anderson’s sublime stoner noir Inherent Vice. Days before shooting the latter, Brolin and his now-wife Kathryn Boyd were on a drunken night out in Costa Rica when a stranger stabbed him in the gut. Only the fluke that the blade went directly into the thick umbilical ligament around his belly button saved his life. “I’m not going to win the lottery,” he says, shaking his head with a laugh at his luck. “I just get to live.”

It was one of many moments that convinced Brolin, in 2013, that it was time to get sober. “I’m not proud of a lot of stuff I did,” he reflects. “I was pretty crazy back then. I was very reactive when I drank.” He recognised the darker sides of his mother’s character in himself, and realised he didn’t want his story to end the way hers had. “Having a mother like Jane was amazing, but it was also awful,” he says. “I don’t really wish that on anybody.” He wanted something different for his own kids. “It wasn’t necessarily a conscious choice, but it’s about breaking that chain. I think they thought: ‘He’s a good dude, but he’s crazy.’ That was the general perception. When I first got sober, Eddie Vedder said to me: ‘Surprise everyone with a happy ending.’”

So he did. There were the blockbuster roles as Thanos, the finger-snapping baddie bent on wiping out half of all life in the box office-conquering Avengers films, and meaty collaborations with Denis Villeneuve in the tightly-wound thriller Sicario and both instalments of sci-fi epic Dune. More importantly, for Brolin, there was the chance to prove himself the writer he’d always hoped to become. Along with the memoir he’s written a play, A Pig’s Nest, also partly inspired by his wild, wildlife-filled upbringing. Meanwhile, at home, he sees bright flashes of his mother’s sense of freedom in his two young daughters, whose toy unicorns and baby dolls are strewn colourfully around inside the

truck.

We’re finally nearing the base of the mountain. As we hit the layer of fog that lingers above the Pacific Coast Highway, our phones chirrup to life to let us know we’ve returned to the zone of phone reception. I tell Brolin he can drop me anywhere I can call a car, but he won’t hear of it. He’s already decided he’s driving me home himself, hours out of his way. Maybe because he can’t bring himself to leave me stranded on the roadside, like the deer up the mountain. Maybe because he hasn’t finished telling me about the surprise of a happy ending.

Right before his mother died, in 1995, he was visiting her at home when he found her crying in the kitchen. Not from pain, but from pride. She was developing a TV idea about animal rescues, and for the first time in her life felt she was being taken seriously. “Her whole life she had felt like the woman with the beard, the snake with two heads,” Brolin explains. “She was just opening up to the fact that maybe she wasn’t just a freak… and then she died. For me to live that out, and to get past my own reactive Cito Rat mentality… there was survivor’s guilt for a while, but now it’s up to me to celebrate every moment I get to keep going.”

The old stereotype that Los Angeles is a shallow place obsessed with appearance and ephemeral beauty doesn’t hold much water when measured against the impressive number of world-class museums the city has to offer. Not only are the following institutions filled with fascinating treasures, artefacts and artworks from around with world, they’re often based in truly beautiful buildings in their own right, and home to relaxing gardens, sun-kissed courtyards and unparalleled views. These are the museums that are not-to-be missed in the City of Angels.

Los Angeles might be most readily associated with Hollywood’s celluloid dreams, but it’s also heaven for art collectors. The city is dotted with a panoply of contemporary galleries, ranging from purpose-built spaces to converted studios and strip-malls. Here you’ll find emerging American artists side-by-side with the best international talent, and museum-quality collections vying for room beside urgent and thought-provoking street art. Los Angeles, famously, is a patchwork of contrasting scenes and neighbourhoods, but one thing that unites them all is that this has always been a place to see and be seen. That’s never been more true than at these trailblazing art galleries.

“Well, I’ll be damned,

Here comes your ghost again…”

Joan Baez, also known as the “Queen of Folk”, is halfway through writing a song one day when she gets a call from Bob Dylan. It’s 1974; almost 10 years after their relationship ended. The song went on to become the iconic ‘Diamonds and Rust’, an outpouring of memories from their time together in the early sixties.

Music writer Kevin EG Perry tells the story behind Baez and Dylan’s relationship, how they shaped each other’s worlds, and how this song came into being a decade later. Folk legend Judy Collins, also a good friend of Joan Baez, shares old memories of Newport Folk Festival alongside more recent memories of performing ‘Diamonds and Rust’ with Baez at her 80th birthday. And we hear from people whose lives have been touched by the song. Classicist Edith Hall listened to ‘Diamonds and Rust’ on repeat when she ended her first marriage, on the night that the Berlin Wall fell. And writer John Stewart looks back on a heady relationship from his early twenties, which was always bound up with the lyrics of this song. Decades later, this formative time in his life continues to resonate with diamonds, rust, and gratitude.

Producer: Becky Ripley

They were supposed to be real-life fountains of youth. In March 2000 the term “Blue Zone” was first used to describe Sardinia, an Italian island that appeared to be home to a statistically improbable number of people living past the age of 100. In the decades since, four more areas have been identified around the globe where locals apparently have an increased chance of becoming a centenarian: Okinawa in Japan; Nicoya in Costa Rica; Ikaria in Greece and Loma Linda in California. These so-called Blue Zones have inspired countless studies, cookbooks, travel stories and even their own Netflix documentary series (2023’s Live to 100: Secrets of the Blue Zones). The trouble is, the outlandish claims about the life-giving properties of these regions just don’t stand up to close scrutiny.

Last month, Dr Saul Newman of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing was awarded the Ig Nobel Prize for his work debunking Blue Zones. Newman’s investigation into serious flaws in the data about the world’s oldest people saw him take home an award that has been handed out since 1991 for scientific research that “makes people laugh, and then think.” Newman says that when he looked into the claims about Blue Zones he found a pattern of significant data being routinely ignored if it didn’t fit the desired narrative, and statistical anomalies that could be better explained by administrative errors or cases of pension fraud. “It’s as if you gave the captain of the Titanic nine goes at it and he’s smacked into the iceberg every time,” Newman tells The Independent of the research. “What’s most astounding is that nobody in the academic community seems to have thought it’s ridiculous before this. It’s absurd.”

Take Sardinia, the original Blue Zone. While it was purported to be home to crowds of centenarians, EU figures show that the island only ranks around 36-44th for longevity in the continent. Many of those who were supposed to have reached very old age in their Italian idyll turned out to in fact be dead, they just hadn’t been reported as such to the authorities. “Sometimes the mafia is involved, sometimes it’s carers,” says Newman. “There’s a lot of cases in Italy where younger relatives have just kept claiming the pension even though granddad’s out the back in the olive garden.”

Bill Gates didn’t see the conspiracy theories coming. The Microsoft co-founder built one of the most immense fortunes the world has ever seen with his foresight about the personal computer revolution, but he never predicted so many people would end up using those machines to cast him as a baby-guzzling, shape-shifting lizard who puts microchips in vaccines and plans pandemics for profit. “I thought the internet, with the magic of software, would make us all a lot more factual,” he laments, a wry smile playing beneath his black-framed spectacles. “The idea that we kind of wallow in misinformation… I’m surprised about that.”

Not that he’s complaining. “I don’t care how I’m perceived,” the 68-year-old assures me over a video call (Microsoft Teams, naturally) from his office in Kirkland, on the banks of Lake Washington, opposite Seattle. So even when “a woman came up and yelled at me that I implanted stuff in her, that I was tracking her” he took it in his stride. “My life is fantastic,” he says. “I’m the luckiest person alive, in terms of the work I get to do.”

Online misinformation troubles Gates not because of his personal reputation, but because it’s the rare problem he doesn’t have an answer for. In his new five-part Netflix documentary series, What’s Next? The Future with Bill Gates, the multibillionaire shares his optimistic vision of a world where scientific innovation rolls back climate change and eradicates deadly diseases while advances in artificial intelligence leave us all free to enjoy perpetual leisure time. It’s just the conspiracy theories that have him stumped. “I feel a bit like we’ve handed that to the younger generation,” he says. “Both to face up to and to figure out: ‘Okay, what’s this boundary between free speech and incitement to violence, or harassment, or just craziness that gets people not to take health advice?’”

Gates is well aware that one reason grotesque and outlandish rumours about him capture the public imagination is because, as he puts it in the show, “extreme wealth brings with it questions about your motives”. He stepped down as CEO of Microsoft in 2000 to establish the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation with his then-wife, aiming to give away “lots of money to save lots of lives”, yet he remains one of the world’s richest people (seventh on the real-time Forbes list, with an estimated net worth of $138bn).

I ask him directly whether he can reassure me that billionaires do have the best interests of the rest of us at heart. His answer doesn’t exactly set my mind at ease. “I’m a huge believer in the estate tax [the American equivalent of the UK’s inheritance tax] and more progressive taxation,” he replies. “I don’t think we should generally generationally let families whose great grandfather, through luck and skill, accumulated a lot of wealth, have the economic or political power that comes with that.”

Not a ringing endorsement of the billionaire class, then. Would he agree that he is too rich? “If I designed the tax system, I would be tens of billion dollars poorer than I am,” he nods. “The tax system could be more progressive without damaging significantly the incentive to do fantastic things.”

Scrubs creator Bill Lawrence has reacted to Vince Vaughn’s comments about R-rated comedies, saying that producers don’t know what they want until they see a formula become a success.

Vaughn recently said Hollywood producers “overthink it” and have become too risk-averse to gamble on R-rated comedies that aren’t based on a pre-existing IP.

Lawrence wrote and produced Vaughn’s new crime comedy series Bad Monkey, which arrives on Apple TV+ on August 14.

An adaptation of the 2013 New York Times bestselling novel by cult Florida crime writer Carl Hiaasen, Lawrence describes the series as the sort of show “you don’t see anymore… banter-driven, R-rated comedies that actually have some real stakes.”

“I hope it works,” Lawrence told The Independent. “Because the second one works, everyone wants it.”

Jonathan Jacob Meijer says he didn’t mean to become The Man with 1000 Kids. For a start, the Dutch sperm donor at the centre of Netflix’s unsettling new three-part docuseries disputes the figure in the title, claiming the real number of donor children he’s helped bring into the world is closer to 600. In the show, the 42-year-old former high school teacher and Crypto trader is portrayed as a zealot determined to spread his seed as far and wide as possible. Mothers from all over the world, who have been having his children since 2007, speak out against him. “I never had the idea to have 100 children or 500 children,” he tells me, speaking down the line from the Netherlands. “It happened step by step. Many donors want to be in the news, but for me if nobody knew about me that would be absolutely fine. Now they do know about me, so I want to explain my side of the story.”

Meijer’s journey to become one of the world’s most prolific sperm donors began when he was at college, where he got talking to a friend who was unable to have children of his own. “He was the first person to put the idea of sperm donation in my mind,” recalls Meijer. A period of introspection followed, as he weighed up how becoming a donor could change his life. A year later in 2007, aged 25, he signed up at a sperm bank. “At first it was really great,” he remembers. “I knew that the people who got my sample would be super happy, and they’d create a family. That’s something meaningful and real.” As he became more at ease with the idea of being a donor, he began to see it as a shame that he had to remain anonymous. “I thought it was a pity I couldn’t meet people and see the smiles on their faces,” he says. “Then I read about websites where you could donate privately, and I realised it was something I wanted to do as well. It felt more complete to me.”

He posted adverts with photographs showing off his long, blonde hair, on Dutch websites where women sought out sperm donors, explaining who he was and his motivations. Right from the start, he says the response was overwhelming. “From the moment I put up the advertisement, an hour later there were four or five emails already. That would go on the whole day,” he explains. “People think I had this plan from the start, but I thought I’d maybe help one or two people.” Instead, he says he found himself filtering through masses of responses. “I know people think I’m crazy and that I help too much, but in my opinion I was super selective,” he says. “People really don’t understand the shortage of donors.”

When Kiefer Sutherland announced the death of his father, Donald Sutherland, at the age of 88, he called him “one of the most important actors in the history of film”. If the claim sounds hyperbolic, it is borne out by celluloid history. The elder Sutherland’s film career began in the early 1960s and spanned seven decades and more than 150 features to the present, with his final performance coming in last year’s western series Lawmen: Bass Reeves. His CV includes classics across several genres, including the 1970 anti-war satire M*A*S*H, the 1973 thriller Don’t Look Now, and his more recent appearances in The Hunger Games. At 6ft 4in, he was a towering presence on screen and cast a lengthy shadow.

Donald McNichol Sutherland was born in the Canadian east coast seaport of Saint John, New Brunswick on July 17, 1935. His parents were Dorothy and Frederick, who ran the local gas, electricity and bus company. His first word, he once told Esquire, was “neck”. “My mother turned around and said, ‘What did he say?’” Sutherland recalled. “My sister said, ‘He said, neck.’ My neck was killing me. That was a sign of polio. One leg’s a little shorter, but I survived.”

Joan Baez was 28 years old and six months pregnant when she walked out on stage to headline Woodstock in August 1969. It was late enough that Friday had become Saturday, so she greeted the tired and tripping masses with a bright: “Good morning everybody! Thank you for hanging around.” Over the next hour she held them spellbound with songs written by the likes of Willie Nelson, The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, having helped to usher Dylan into the limelight just a few years earlier when she invited him on stage with her at Newport to duet on the protest anthem “With God on Our Side”.

Only one song, “Sweet Sir Galahad”, was a Baez original. “It’s the only song I’ve ever written that I sing anywhere outside the bathtub,” she announced over the mud. “Because I’m just smart enough to know that my writing is very mediocre.”

Baez no longer thinks her writing is mediocre, but this revelation came to the 83-year-old only recently. “I started getting more confident about three months ago,” she says, with a musical laugh that lets me see the diamond embedded in gold in one of her teeth. It’s easy to think of Baez as the original long-haired folkie, but these days, with her silver pixie cut and twinkling tooth, there’s a touch of the rock’n’roll pirate about her. “People said to me so many times, ‘But they’re good songs!’ So I went back and listened… and they’re good songs!”

Baez released the last of her 25 albums in 2018, and retired from touring the following year. Today, she’s at her rural home in Woodside, outside Palo Alto in northern California, speaking to me over video call from in front of an antique wooden organ in her kitchen, surrounded by copper pots and candles. She is about to publish her first collection of poetry, When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance, which offers further evidence that Baez’s vivid, expressive soprano and unerring ability to fuel her activist politics with song are far from the sum of her talents.

Jon Bon Jovi takes a sip from a bottle of water and flashes that unblemished smile. The stadium-filling rock star has somehow always managed to retain a reputation for clean living. He may have come of age amid the excess of Eighties hair metal, but the 62-year-old has resolutely steered clear of at least the narcotic element of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. As he tells me via video call from London, it was a bad experience in his youth that kept him on the straight and narrow over the next four decades.

“It was smoking something that was laced with something else, and I remember feeling out-of-body high and thinking, ‘I don’t like this. I don’t feel comfortable with this,’” he explains, leaning forward in his chair. “It was scary, and I was so young that I was glad I had that sort of ‘scared straight’ moment.” At least, when his vocal cords atrophied catastrophically in 2022, he knew it wasn’t due to any drug habit. “I couldn’t blame it on putting anything up my nose,” he laughs. “The only thing that’s ever been up my nose is my finger!”

Years of living healthily have served Bon Jovi well. His heartthrob grin is still intact, and his hair, albeit now a shock of white, has retained its famously tousled “run your hands through it” look. Dressed in a tight black T-shirt, he exudes a youthful ebullience, slipping comfortably into the role of raconteur. There is, though, a touch of pathos to his laughter. The last tour by his group Bon Jovi, one of the world’s most successful rock bands with over 120 million albums sold, came to a grisly end in April 2022 with the singer collapsed on the floor of his dressing room in Nashville, his voice shot. That summer he underwent cutting-edge surgery to repair his vocal cord, fully understanding the risk that he may never tour again.

Wim Wenders’s new film Perfect Days is perhaps the only Oscar nominee in history to be based on a series of Japanese public toilets. Just when you thought we’d exhausted every conceivable type of intellectual property, here comes the German auteur to offer a whole new definition of IP. In 2022, Wenders was approached by the Tokyo Toilet art project, which had commissioned leading architects and designers to create 17 toilets spread across the city’s fashionable Shibuya district. They hoped Wenders might make a documentary about their sparkling new facilities. Instead, he envisioned a simple drama about a man who cleans them.

We get to know Hirayama (Koji Yakusho) through his daily routine: the toilets he cleans thoroughly and methodically, the public baths where he does the same to himself, and the frequent commutes where he listens to his favourite music on cassette tapes that intrigue and baffle the film’s younger characters. These tapes are the key to unlocking his character, so when Wenders decided to open the film with Hirayama sliding in a battered cassette of The Animals’ eerie 1964 recording of “The House of the Rising Sun”, he worried it might not be the right choice.

“I felt I was imposing myself, and that this was cultural appropriation,” says the grey-haired 78-year-old thoughtfully from a hotel room in London, eyes twinkling behind blue-framed glasses. “I said, wait a minute. This is a Japanese character a few years younger than me, can I impose my musical taste? This is not a good thing!”

When Hollywood needs a bad guy, Ben Mendelsohn will answer the call. The 54-year-old Australian was on hand to help Darth Vader develop the Death Star in 2016’s Rogue One, and stomped his way around Sherwood Forest as the Sheriff of Nottingham in 2018’s Robin Hood. His filmography is stacked full of scummy, shady characters who’ll menace your grandmother as soon as look at her, but that’s all a far cry from the thoroughly charming bloke I find myself in conversation with one sunny Friday morning.

“Do you mind if I smoke?” he asks as we settle in. “Does it bother you?” Given that we’re speaking over video call from opposite sides of Los Angeles, I figure I’m probably safe from second-hand smoke. Still, it’s polite of him to ask. He grins impishly as if to say, well, you can’t be too careful these days. “You know,” he says, with a wave of his soon-to-be-lit cigarette, “2024!”

Mendelsohn is at home in Silver Lake, in a navy blue sweater and a pair of black-framed glasses that he habitually removes to gesticulate with, as a sort of counterweight to the cigarette in his other hand. He’s eager to tell me about his latest role, which isn’t a baddie at all. He’s playing the wildly influential French fashion designer Christian Dior in the Apple TV+ series The New Look, which premieres tomorrow. The show looks tailored to debut as the perfect date show for Valentine’s Day: part haute couture biopic, part Second World War thriller. “Dior is a beautiful guy to play, with his reserve of strength, his fragility and integrity,” says Mendelsohn. “We all know his name, but no one knows anything about him, really.”

George Clinton reflected on the highs and lows of his seven-decade career in music as he was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on Friday (19 January).

The funk pioneer, 82, was honoured with a ceremony that featured speeches from Red Hot Chili Peppers singer Anthony Kiedis, legendary Motown songwriter Janie Bradford and civil rights lawyer Ben Crump.

Hundreds of fans thronged down Hollywood Boulevard outside the Musician’s Union to witness the unveiling of the 2,769th Walk of Fame star.

“This feels good as shit,” Clinton announced. “I’m proud as hell.”

Clinton, who grew up in Plainfield, New Jersey before becoming a songwriter for Motown Records in the 1960s, pointed out that he hasn’t always received such plaudits.

“I learned early on in this journey that you are only as big as your latest hit,” said Clinton. “So you had to keep things in perspective, to keep from getting a big head. I found out that there would be times when it seemed like everyone knew your name. Then were times when no one knew you. I learned to respect the balance.

“If I needed to hear my name spoken out loud, I would go to the airport and page myself! That’s how fickle the ego is. Sometimes, I might be alone in the mirror and think: ‘I’m all that, I’m a bad motherfucker!’ Then I go ahead and flush the toilet along with the rest of the shit!”

From the moment he first laid eyes on it, Steven Donziger knew he had to do something about the oil. It was 1993, and the newly graduated human rights lawyer was in Ecuador investigating allegations that Texaco had dumped billions of gallons of toxic waste in the Amazon rainforest.

“I expected to see pollution, but I was shocked at the level of it,” he remembers now. “It was just blatantly out there on the floor of the jungle. Olympic swimming pool-sized lakes of oil that had been placed there deliberately by Texaco, then left and abandoned. They were leaching into the soil. There were pipes draining into the streams and rivers that people were drinking out of. It was obvious it was an apocalyptic nightmare.”

That moment lit a fire in Donziger that still burns to this day, 30 years on. Beneath swaying palm trees in a hotel bar in Santa Monica, the 62-year-old is speaking passionately about the case that consumed his life. At 6ft 4in, with close-cropped grey-white hair, he cuts a commanding but good-humoured figure, especially considering that until a few months ago an ankle tag had kept him confined to his Manhattan apartment for 993 days.

Luna Luna, like a dream, almost vanished from memory. In 1987, in Hamburg, the Austrian pop-star-turned-artist André Heller threw open the gates of a one-of-a-kind fairground. Inside, wandering circus acts performed in front of carousels and carnival rides designed by a crew of the greatest artists of their time. Some were already world famous, like Salvador Dalí, David Hockney and Roy Lichtenstein. Others were eccentric Europeans or the rising stars of the New York street art scene: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf and Keith Haring. That summer, 300,000 lucky visitors swarmed into the park, immersing themselves in colourful, radical, witty, sometimes scatological art. Then, like a circus leaving town, Luna Luna packed up and disappeared.

Himesh Patel began his acting career in a state of panic. It was 2007, and on the morning of the then 16-year-old’s final GCSE exam, he received a phone call asking him to audition that afternoon for a role on EastEnders. The moment he finished the test, his dad rushed him to the casting. It was only as Patel read the character description that his nerves subsided. He was up for the part of Tamwar Masood, a somewhat geeky, studious boy with an older sister, whose parents ran a post office. All of that was true of Patel, too, and he aced the audition. He was a working television star before he’d even started his A-levels, but his real-life parents weren’t going to let him get swayed by glitz and glamour.

“I did the paper round until I was 21,” remembers Patel now, a little incredulously. “For five years of doing EastEnders, I was still doing the paper round. I hated it at the time, but looking back it kept me in check and stopped me getting carried away with being on telly and being mildly famous.”

Patel spent nine years on the long-running BBC soap, taking Tamwar from a bit-part character to a much-loved fan favourite who unexpectedly became a stand-up comic and married Danny Dyer’s onscreen daughter. Since leaving the show, he’s continued to confound expectations: first, by landing the lead in Danny Boyle’s Beatles-inspired romcom Yesterday, then by popping up as a suave fixer in Christopher Nolan’s Tenet and as Jennifer Lawrence’s journalist boyfriend in the end-of-the-world satire Don’t Look Up. In some ways, his rise is a remarkable one; in others, it is perfectly comprehensible. Patel is a natural everyman, with a quiet charisma and an earnestness that acts as a sort of narrative lightning rod. No matter how unfamiliar the world or outlandish the plot twist, Patel can ground it, make it real.

Danny Trejo knows he’s being watched. Glancing over his shoulder, the 79-year-old flashes a wide, toothy smile at the women a couple of tables down from us who’ve just clocked the presence of the baddest of all badasses. ‘No way!’ they exhale in unison. Trejo turns back to me, still grinning, and digs a tortilla chip into a mound of guacamole studded with pistachios. ‘Someone once told me I was the most recognisable Latino in the world,’ he says. ‘I went, wait, am I ugly or what?’ He erupts into a throaty laugh that reverberates like gravel in a cement mixer, then shakes his head. ‘Nah, you’ve just been in a lot of movies, holmes.’

To be fair, it’s hard to stay incognito when your face is plastered all over the walls. We’re having lunch at Trejo’s Cantina, a bright, colourful taco joint in the heart of Hollywood, with a full bar and a recurring motif in its choice of artwork. Trejo’s moustachioed mug stares out from hot-sauce bottles, staff T-shirts and the sign above the door. In the toilets, murals depict just some of his more than 400 film, television and video game roles: thrusting open a trench coat full of blades as Mex-ploitation action hero Machete, taking the mic in From Dusk Till Dawn, his severed head riding across the desert on a tortoise in Breaking Bad. If you didn’t recognise Danny Trejo in this place, you never would.

The quintessential screen tough guy opened his first taqueria a few miles south of here on La Brea Avenue in 2016, and now has five Trejo’s Tacos locations dotted across Los Angeles. Next he has his sights set on London, specifically a prime spot on Portobello Road. He fell in love with the city a decade ago while shooting Muppets Most Wanted. ‘I stayed there for about four weeks,’ he remembers. ‘Me and Ray Liotta walked all over. It was a joy. People are so friendly, especially because me and Ray are pretty recognisable. We went to see Buckingham Palace and were complete tourists. But both me and Ray said: “They need some Mexican food here!”’

This June, when Tupac Shakur belatedly received his star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, a crowd of hundreds turned out for the occasion. Pressing up against steel barricades, they rapped his songs and chanted his name. Almost three decades after his death, Shakur still feels powerfully alive. He was a star for just five years, from the release of debut album 2Pacalypse Now in 1991 to his death in 1996 at just 25 in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas, for which nobody was charged until a few months ago. Despite the brevity of his time in the spotlight Shakur released four albums – three of which went platinum – and appeared in six films. That work – and the 75 million record sales that followed – have ensured a kind of immortality. It’s no coincidence Dr Dre and Snoop Dogg brought him back as a hologram for Coachella a decade ago. Apparently untroubled by death, Shakur has always stayed relevant.

While Shakur may now be an icon to millions, when Staci Robinson first met him he was just an incredibly confident 17-year-old with a notepad full of ideas. They attended the same high school, a few years apart, and Robinson went on to become a novelist and screenwriter. They kept in touch, with Shakur inviting Robinson to join a scriptwriting group he was planning to put together out of a desire to create female characters with authentic perspectives and voices. The first meeting was scheduled for 10 September 1996, three days after Shakur was shot and fatally wounded.

A few years later Shakur’s mother Afeni, who died in 2016, asked Robinson to write a book about her son. After months of interviews with those who knew him best the project was put on hold, where it remained until Robinson’s involvement in last year’s museum exhibit Wake Me When I’m Free and this year’s documentary miniseries Dear Mama. As with those projects, her newly published Tupac Shakur: The Authorized Biography takes Shakur off his pedestal as one of the greatest rappers of all time and instead lets us see him as a mother’s son, shaped first by Afeni’s revolutionary politics and then often again by the women he spent time with.

Shortly before the outbreak of the pandemic, Danny Brown sold his house in the suburbs and moved to a penthouse apartment in downtown Detroit. “I’d just went through a break-up,” explains the 42-year-old underground rap maverick, his voice mellow as it drifts down the line. “I was moving there because there were more parties. I was going down there to be a ho! To party and shit.” He chuckles quietly to himself. Things didn’t quite work out that way. “When everything got locked down,” he remembers, “I just found myself in this big-ass penthouse apartment. Alone.”

Brown, newly single and approaching 40, threw himself into his writing. “I was just doing something to stay busy,” he says. “Music has always been like a form of therapy for me, so I just was getting my feelings out.” During those surreal days of lockdown, he found his mind drawn back to where he’d been ten years prior. It was Brown’s second album ‘XXX’, released in 2011 shortly after he turned 30, that made him a star. An audacious autobiographical concept record with an A Side of party songs and a B Side filled with more

thoughtful, contemplative bars, he wondered if he could repeat the trick for his 40th. “It was just like a: ‘Can I do it again?’ type of feeling,” he says. “When most people have a breakout project, people just know them for that and think: ‘They can’t do that shit again!’ It was me proving to myself that I can still make that kind of music.”

The result is Brown’s electrifying sixth ‘Quaranta’ – named for the Italian word for 40, as well as a nod to its birth during quarantine. Living just around the corner from his studio, a house on Detroit’s Grand Boulevard, on the same strip as the Motown Museum, meant Brown never had to look far for inspiration for Side A. “It was like a non-stop party, man,” he says. “I was always getting fucked up.” That attitude bleeds into songs like ‘Tantor’, which Brown recorded while in the midst of a deep acid trip. “I was super into Parliament at the time, and we talked about how George Clinton would take acid, get in front of the mic and just start saying shit,” he remembers, “So that was really the first song I never wrote. I just took a lot of acid, stood up to the mic, and it came up. I mean, I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone. I’m not trying to glorify it or anything, but I was still deep in my addiction at the time.”

In the gloomy grandeur of a Spanish Gothic theatre in downtown Los Angeles, singer Ian Astbury and guitarist Billy Duffy are reaching into the deepest recesses of their back catalogue. As the songwriting partnership at the heart of The Cult, the pair helped pioneer the first wave of Gothic rock and went on to become one of the decade’s biggest and most influential bands, filling stadiums and in heavy rotation on MTV. But before any of that, they were a post-punk band called Death Cult, making raw, impassioned music that howls viscerally about the plight of Native Americans and the horrors of war. Tonight is a resurrection of sorts, a one-off American show ahead of a UK tour. Before the set closes with the majesty and mass euphoria of 1985’s “She Sells Sanctuary”, Astbury pauses for just a moment. “Thanks,” he says, his face smeared with white make-up and sweat, “for the rebirth of Death Cult.”

A week later, Astbury meets me for a curry at a hole-in-the-wall Indian restaurant in Hollywood beneath the Capitol Records Building. Dressed head-to-toe in black, the 61-year-old may have mountains of stories – from rock’n’roll hijinks to seeking spiritual enlightenment among the monks of Tibet – but he maintains a healthy aversion to nostalgia. “I don’t really live in a time machine,” he tells me, digging into a plate of saag chicken, rice and vegetables. “If you come to my house, I don’t have any discs on the walls or photographs and memorabilia. Actually, in 1995 I put it all on the barbecue and set it on fire.”

The decision to return to Death Cult after 40 years might seem counterintuitive, then, but for Astbury it felt like too poignant and auspicious an opportunity to pass up. “The 25th anniversary? Whatever! 30th? No. But this time I felt something different,” he says. “For Billy and I, it’s been incredible, because we go, ‘Oh, this is our DNA, where we came from.’”

Joni Mitchell and Leonardo DiCaprio were among those who gathered to celebrate the life and music of the late The Band guitarist and singer-songwriter Robbie Robertson last night (15 November).

The memorial, held at Robertson’s longtime Los Angeles studio home The Village, included a moving tribute from director Martin Scorsese and performances of Robertson’s music from Jackson Browne, Citizen Cope, Angela McCluskey and others.

Robertson died after a long illness on 9 August, aged 80.

Scorsese and Robertson first met while making The Band’s legendary concert film The Last Waltz. “I guess when all is said and done it was a kind of folie à deux,” said Scorsese in his eulogy. “That is, two individuals came together and did something that on their own they wouldn’t have done.”

Initially planned as simply a live recording of the group’s 1976 farewell concert, Scorsese and Robertson spent two years working on the film together. “During those two years Robbie stayed in the house, we had informal classes,” Scorsese remembered. “Music class for me, film class for him. He introduced me to obscure blues music, gospel, and the Sacred Harp Singers. I introduced him to Sam Fuller movies, Pasolini’s Accattone, Visconti… We really shared what we loved.”

The pair continued to collaborate on films including 1980’s Raging Bull, 1995’s Casino and 2016’s Silence. Scorsese recalled Robertson sending him four CDs full of musical suggestions for 2006’s The Departed. The opening track was Dropkick Murphy’s ‘I’m Shipping Up to Boston’, which Scorsese ended up using repeatedly in the film.

Most recently, Robertson composed the music for Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. A medley from the score was performed at the memorial by an orchestra conducted by Mark Graham. Other musical performances included Angela McCluskey singing ‘Whispering Pines’, Jackson Browne covering The Band’s ‘Caledonia Mission’ and a singalong finale of ‘The Weight’ featuring Browne, Jason Isbell, Blake Mills and Tal Wilkenfeld.

Welcoming guests to the event, The Village Studios owner Jeff Greenberg recalled the effect Robertson could have on the bands who came to record while he was around.

“Everybody who ever came here wanted to go so hi to Robbie,” he said. “‘Robbie, so-and-so’s here, they want to see you.’ ‘Sorry, tell them I’m busy.’ Occasionally he would bestow his presence on people, like Elton John, Leon Russell or U2. One little group was here, I couldn’t believe, he went down and say hi to Wolfmother. It was like they’d been kissed on the forehead by God. They’re still glowing.”

It’s a Wednesday night in October, and the mall belongs to Taylor Swift. The Grove, one of Los Angeles’ most popular high-end shopping centres, has been shut down all day in preparation for a very special film première. Or rather, premières. When Taylor Swift takes over a cinema, she doesn’t use one screen. She uses 13.

For some of those in attendance, tonight is their first chance to witness a multi-faceted stage spectacular they’ve previously been unable to see in person. For others, it’s an opportunity to relive what might just have been the best night of their lives. Together, they sing. They hoot and they holler. The aisles fill with dancers. “It was like being back at the tour!” says Chloe, a dedicated Swiftie who was invited to attend the screening. “I loved it so much! Taylor is always so dedicated to her fans and to her craft. All she wants to do is satisfy the fans, and she does it every single time!”

When Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour was officially released the following day, you could find perfectly satisfied Swift fans singing their hearts out at cinemas across the planet. In the US, The Eras Tour racked up $96 million in ticket sales in its opening weekend alone, smashing the previous concert film record of $73 million set by Justin Bieber’s Never Say Never back in 2010. The following weekend it held firm at top spot, beating Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon and in the process becoming the first concert film in history to spend two consecutive weeks at the pinnacle of the cinematic box office.

Pete Townshend had a vision. In 1970, in between writing Tommy and Quadrophenia, the then 25-year-old guitarist and songwriter started work on a rock opera set in a Britain suffering ecological collapse. With pollution choking the air, an autocratic government keeps the population docile with a constantly streaming entertainment network known as “The Grid”. Townshend called this ambitious project Lifehouse, but when plans for a movie version fell through and it became clear that even his bandmates were struggling with the convoluted plot, he admitted defeat and repurposed the bulk of the music for a conventional rock album, Who’s Next. Bookended by a pair of indelible anthems, “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again”, the record, born of compromise, is often considered The Who’s finest work.

Now, over half a century later, the band have released an expansive 11-disc box set, showcasing not just the majesty of Who’s Next but also a trove of Townshend’s home demo recordings that sketch out what Lifehouse – now called Life House – might have been. The timing seems apt. On the day Townshend and I speak over video call, the prime minister has just announced the rollback of a swathe of key environmental policies across the UK. As miserable as the news is, I can’t help but ask whether Townshend gets some sense of vindication from knowing he saw this future coming all those years ago.

“Fuck!” he replies, gloomily. He’s at home in the English countryside, wearing a black beanie and some serious-looking headphones. His white goatee is neatly cropped, and he has the air less of a veteran rock star than of a particularly curmudgeonly academic. “I don’t know about Rishi Sunak,” he continues. “I don’t know about the Tory party, per se. They say, when you get older, you drift from being on the left to on the right. I suppose there was a gentle drift with me. I’m 78, and between 60 and 70 I think I was starting to drift slowly to the right, but… fuck!” That expletive is followed by a reckless outburst of anger: “I would line them all up and shoot them.”

The arrival of a new Rolling Stones album is a momentous occasion. Yesterday afternoon (September 6), at an exclusive event at east London’s Hackney Empire, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood confirmed that the 24th Rolling Stones album ‘Hackney Diamonds’ will arrive next month on October 20. It brought to an end weeks of speculation following a cryptic newspaper advert published a couple of weeks ago that had led an excited friend to text me: “I’m hoping this ‘Hackney Diamonds’ bollocks is what I want it to be!”

You see, new Rolling Stones albums are things worth getting worked up about. For a start there hasn’t been one for 18 years, which is so long ago that back then I had to go to Woolworths the day it came out to buy it on CD, like we used to in the old days. For most bands that would be a lifetime ago, for the Stones it’s a long weekend. After all, they’ve been putting out albums for almost six decades.

Making wine in California is a competitive business. While the north of the state is home to some of the most celebrated grape-growing regions in the world, in the last few years many young winemakers who’ve found themselves priced out of Sonoma and the Napa Valley have instead been flocking south to the Santa Ynez Valley. Centrally located in Santa Barbara County, this up-and-coming area has established itself as a cooler, more boutique and (somewhat) more affordable alternative to its powerhouse northern neighbours.

It helps, too, that Santa Ynez is just a couple of hours’ drive from Los Angeles. This prime location has helped the area attract a host of creatives drawn by the more relaxed pace of life and the temperate weather. The Santa Ynez Valley benefits from a geographical quirk: in California, most mountain ranges – and thus valleys – run north to south. In Santa Barbara County, however, the valleys run east to west due to shifts in tectonic plates some 20 million years ago. This means that every morning the area is cooled by a sea breeze, creating a highly desirable climate – and making it a world-class location for growing grapes like Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

The valley comprises six hamlets, each with its own distinctive character. There’s the quaint, Danish-inspired village of Solvang; the historic town of Santa Ynez; the tiny, tasting-room-filled Los Olivos; the growing towns of Ballard and Buellton; and Los Alamos, which is steeped in real-life cowboy heritage. The way the surrounding land is used is another thing that sets the Santa Ynez Valley apart from the more well-known northern Californian wine regions.

“In Sonoma, you have farm country,” explains Daisy Ryan, executive chef and co-owner of Michelin-starred foodie destination Bell’s in Los Alamos. “Down here, it’s ranch country. That history runs deep.”

Rage Against The Machine guitarist Tom Morello played a surprise set on the picket line in front of Paramount Studios in Hollywood today (August 14).

SAG-AFTRA – Hollywood’s largest union, which represents 160,000 actors and performers – and the Writers Guild of America (WGA) are both currently on strike as they seek an increase in base pay and residuals in the age of streaming. They are also hoping to negotiate safeguards against the unregulated use of artificial intelligence in the film industry.

Speaking before the performance, Morello told NME he wanted to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with striking actors and writers: “They’re making history here on the sidewalk in front of Paramount Studios and I’m here to support them and express my solidarity.”

The guitarist, who described himself as a “proud union man”, applauded the actors and writers for “flexing their power and showing what solidarity means.”

He added that the ongoing strikes in the entertainment industry are part of a wider movement of organised worker power across the country that some have dubbed ‘Hot Labor Summer’. “In the United States right now, we have the biggest wave of strikes and organising in about 40 years,” said Morello. “In town right now, we also have hotel workers out [on strike] as well, so the picket lines are hot!”

Morello’s 15-minute set included ‘Union Song’, ‘Hold The Line’, ‘Union Town’ and a cover of Woody Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land’. “I’ve made music throughout my entire life to be played on picket lines and on the front lines,” said Morello. “So today is just one more day at the office with regards to that.”

Paris Texas are just about ready to get off this planet. On ‘Mid Air’, the LA punk-rap duo’s thrill-packed debut album, they trade bars about escaping this doomed rock by saving up enough cash for a one way ticket to Mars. “The sun is whoopin’ everybody’s ass,” they lament. “Earth finally threw in the towel.”

On a blazingly hot afternoon in downtown Los Angeles, it isn’t hard to see how the pair arrived at that apocalyptic conclusion. The sun is indeed whoopin’ everybody’s ass today. In a warehouse studio booked out for their NME cover shoot, rapper-producer Louie Pastel has his shirt off and a weathered MTV cap pushed back on his head. He’s holding a cigarette in one hand and DJing from his phone with the other.

The sounds filling the room are as eclectic as you’d expect of a group that have drawn comparisons with Odd Future and Death Grips but who defy easy categorisation. We hear Louisiana rapper Autumn!, then Brazilian psychedelic samba from Novos Baianos and Radiohead’s acoustic version of ‘Creep’. Beside him, his comrade Felix is weighing up the pros and cons of filming vs photo shoots. “In videos you’re in constant movement, so you’re not stuck on one dumb face,” he ponders. “Models are crazy! I don’t know how they do it.”

Glancing around at his surroundings, it isn’t hard to see why LaKeith Stanfield might, as he puts it, ‘feel adrift in history’. We’re sitting on wooden chairs in a cottage on the grounds of a Pasadena hotel that dates back to the Gilded Age. Stanfield has been living here for the past few weeks while he remodels his nearby home to mimic its rustic aesthetic: exposed oak beams, heavy velvet curtains, wrought iron pokers beside the fireplace. ‘I like feeling like I’m in a different time,’ he says. ‘That’s how this hotel makes me feel.’ It is, he says, his hideaway from the modern world. ‘I’m trying to find a hole and stay there,’ he smiles. ‘Especially these days, I’m really enjoying the things that matter, like family. Building my family and having those moments of sacredness is really important.’

Let’s bear with him for a moment, shall we? ‘I don’t know if it’s start-middle-end,’ he muses, his voice low and languid. ‘I view it as a revolution in a circle, a neverending loop.’ The 31-year-old (at least by conventional calendars) found himself pondering this concept on the set of his spooky new Disney movie, Haunted Mansion. ‘If you think about it like that, technically we’re ghosts,’ he continues. ‘The question is: do you want to be a good ghost or a bad ghost? You’re in someone’s dream right now, and you’re either haunting it or making it more pleasurable. My thing is: let’s make people’s dreams a little bit more fun and cooler, make them feel good if we can.’

Over the past decade Stanfield has established himself as the most compelling, charismatic and idiosyncratic actor of his generation. His lethargic charisma is endlessly malleable, allowing him to drift through time to play an Old West outlaw in The Harder They Fall or a 1960s FBI informant in Judas and the Black Messiah (earning an Oscar nomination in the process). He is best known, though, as the otherworldly Darius, who spent four seasons of Atlanta as the trippiest, most heartfelt character on television.

This June, Liam Fender and his superstar brother Sam fulfilled a long-standing family ambition in a most unexpected way. “The Fender family is all Newcastle United mad, and all really good footballers: my dad, my uncles, my granddad was semi-professional,” explains Liam, speaking over video call from the spare bedroom at home in North Shields. “I came along and I’m fucking useless. I was that shit at football, I got bullied by a PE teacher! It soured the whole thing for us, and Sam’s by no means a footballer. So there was something quite heartening and amusing about the fact that the two shittest footballers in the family are the ones who can say we’ve played at St James’ Park!”

During those two sold-out nights at Newcastle’s Cathedral on the Hill, Liam joined Sam (who’s 9 years his junior) to duet on Bruce Springsteen’s slow-burning 1984 classic ‘I’m On Fire’. Now, Liam is preparing to release debut EP ‘Love Will…’, a rich collection of ballads and bawlers that showcases his knack for melody and sharp turn of phrase, as if Richard Hawley were from a bit further North.

Here, he tells NME about digging into the songwriting vaults he’s built up after 20 years of gigging, starting work on his first album and lending his support to a campaign to help men’s mental health in the North East during the cost of living crisis.