‘We used to squat around here,’ says Pete Doherty, gesturing out of the window. ‘Albion Towers. There, the place opposite the Scala.’ ‘That was my little belfry,’ adds Carl Barât. ‘There’s a tiny little room at the top.’ We’re in the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel. It’s the perfect place for The Libertines to complete the circle: a London gothic fantasy. The Sir John Betjeman suite bears the stamp of its current occupants: the table is covered in empty cocktail glasses, one of which serves as a mausoleum for a steady stream of dead Marlboro Lights.

Barât picks up a book of the late poet laureate’s and reads from ‘A Child Ill’: ‘Oh little body, do not die…’ as we wait for our drinks; they’re called Ring of Roses, a potent concoction of vodka, champagne and elderflower. The summer evening is falling outside: all the scene needs is Chatterton dead on the couch. You can never accuse The Libertines of not staying in character.

A lot has happened since Doherty and Barât, along with drummer Gary Powell and bassist John Hassall, first stuck a needle in the arm of British rock ’n’ roll. Among music’s millionaire rappers and business-class casuals, the Libs wore their wit and mercurial intelligence on their sleeve. The press loved them: in 2002 the NME put them on the cover before they’d had a record out. Their vision of an English ‘Albion’ was a composite of Pete & Dud, ‘Steptoe and Son’ and ‘Oliver!’, with a distinctive London seediness and swagger. At their heart was the singular relationship between Doherty and Barât: loving, co-dependent, doomed. If Britpop had looked to the ’60s, the Libs were the Romantic poets, more Keats than Kinks.

And like the Romantics, they carried the shadow of their own destruction. They were – initially in the best possible way, subsequently in the very worst possible way – a shambles. Within two years of the release of their acclaimed debut, ‘Up the Bracket’, they had disintegrated in a mess of drugs, amateur burglary and prison. Doherty was appointed artist-in-residence to the tabloid media. A reunion looked unlikely.

But now they’re back, with a third album, ‘Anthems for Doomed Youth’. Recorded at Karma Sound Studios in Thailand, close to where Doherty recently completed rehab, the record represents a chance at redemption. After a triumphant set at Glastonbury, they’re headlining Reading Festival and Leeds Festival, and their return is a breath of smoky air to 2015’s clean-living music scene. Maybe we need their uncompromising devotion to the spirit of rock ’n’ roll more than ever. As new single ‘Gunga Din’ snarls: ‘It feels like nothing’s changed/Oh, fuck it, here I go again…’

Does this city inspire you?

Carl: ‘It’s endlessly a source of inspiration. It’s home, isn’t it?’

Pete: ‘My girlfriend has never lived in London, so all the time, when I take her out, I’m telling her stories and reliving things. It must get a little bit annoying for her after a while – “You worked there as well?”’

Was there a moment when the band’s relationship clicked again after the initial awkwardness of getting back together?

Carl: ‘By the time we were in Thailand there was no awkwardness. We were just really eager to get on with [recording the album]. I guess it all clicked when we pressed record and started playing “Gunga Din”…’

Pete: ‘Yeah, that’s true. Just playing together in a room like that.’

Have you noticed changes in each other?

Pete: ‘I never really used to take much notice before, but now we’re being asked to analyse the changes and the differences, just to placate the naysayers. I’m scared to share a microphone with him now because people say it’s a gimmick. Sometimes I do rush over [to the mic], but that’s only because after you’ve had a few drinks and smoked a certain amount you get that really nice smell on your breath. You know, like when your lover has got that winey, smoky taste. Not that Carl’s my lover… I’d rather toss off a frog.’

Carl: ‘That’s why he moved to France.’

Speaking of the two of you as lovers, have you read any Libertines fan fiction?

Pete: ‘Don’t mention that! He gets really annoyed.’

Carl: ‘I wouldn’t even know where to look for it.’

Pete: ‘He’s lying. Someone pointed us in the direction of it. It’s fucking weird, man, isn’t it? A lot of effort has gone into it. There’ll be a poetic stream of consciousness and then suddenly, BANG! My cock will appear in Carl’s ear. I think it must be written by someone close to us, because apart from the actual sex side of things, which obviously isn’t true, some of it’s quite close to life.’

You seem to be getting on better now. Are you older and wiser?

Carl: ‘I think we just understand things a bit better. We called down the thunder, and by fuck did we get it: like a piledriver that squashed the four of us. Now we’re realising a bit what things mean. How little time there is.’

Pete: ‘Maybe it’s the opposite. Maybe we really understood what things meant then, but things are different now in all our worlds. Carl’s got two little children who he loves. They call him daddy, because, well, that’s what he is. He’s a different person. There’s something in his eyes that wasn’t there before. Something fast approaching happiness.’

Now you’re back together, I see you’re still finishing each other’s…

Carl: ‘…Sandwiches.’

Exactly. How did you deal with being in the tabloids all the time?

Pete: ‘To be honest I’ve always been more of a TLS reader myself. I never really bothered. Sometimes you can’t avoid it, when it’s in your face when you’re buying milk.’

Carl: ‘I’m more interested in the crossword.’

Pete: ‘Or you find yourself in the fucking dock because someone’s taken a picture of you from a funny angle that makes it look like you’re doing something you’re not. The tabloids can fucking kiss it, man. As soon as I get 12 Number Ones I’ll buy them out and have a huge bonfire. All the fucking journalists will be tied up, gagged and bound in flammable gaffer tape. All the people saying “Pete Doherty’s put on weight”: they’ll see! I’ll lose a stone as the sweat pours from me while their carcasses go up in flames. The squeals of their last breaths…’

Carl: ‘It’s been a long day.’

You’re headlining Reading Festival. Will that feel like a homecoming?

Carl: ‘Reading is always a homecoming. It’s where I first stood in the mud and didn’t understand why someone was shouldering me to the ground. I got up with a bloody nose and realised that it was fun. It was abrasive love, and that’s what people do in front of a band that they love.’

Is there a pressure on you returning to the fans after ten years?

Carl: ‘A lot of them weren’t there then. You see a lot of 15-year-olds in the front row. We’ve just got to do what we do. If what we do is true but it isn’t good enough, then that’s a whole different issue.’

Pete: ‘Pressure really only exists when you have two opposing forces. If all the forces are pushing in the same direction then you just let the energy flow, and utilise it. There’s no one out there now to prove anything to.’

Does it feel more permanent now?

Carl: ‘We’re forever in the moment. There never has been any permanency to our state of mind.’

What advice would you give to a young band just starting out?

Pete: ‘You should start that question “Is there any advice…”’

Is there any advice…?

Pete: ‘No.’

Carl: ‘Nothing apart from “Keep the faith!” It’s the hardest thing in the world, and the easiest.’

Pete: ‘Just don’t listen to the naysayers who say that it’s a crap idea to put on this certain event at this certain place. Just do it. Play the really dodgy pub at the end of the street. You could meet a songwriting partner. You could get a blowjob. I don’t know.’

Carl: ‘You could get both, if you read the fan fiction.’

Do you still get nerves before big shows?

Pete: ‘That ain’t even the word, mate. “Nerves” ain’t even the word. Heebie-jeebies.’

Carl: ‘Fucking fear. Terror.’

It hasn’t changed with age?

Pete: ‘The day we just skip on [stage], we’ll knock it on the head.’

Carl: ‘That is the metaphor of “The Elves and the Shoemaker”. At the end, they’re given clothes and they all go away happy.’

Pete: ‘That’s what we’re looking for. The day the demons go away.’

Carl: ‘Then we won’t need to play songs any more.’

So that’s The Libertines in 2015: the same but different, as vital as ever. How long they will hold it together this time is anyone’s guess. ‘Gunga Din’ also contains a warning: ‘The road is long/If you stay strong/You’re a better man than I.’ What makes The Libertines unique also makes them uniquely fragile. The Ring of Roses cocktails arrive. ‘Chew the elderflower,’ advises Doherty. Then: ‘How old are you?’ ‘Twenty-nine,’ I reply.

He leans in conspiratorially. ‘Got any drugs?’

Originally published in Time Out, 25 August 2015.

Read in Russian at Time Out Moscow.

Marvel at Morocco’s mystical master musicians

Marvel at Morocco’s mystical master musicians

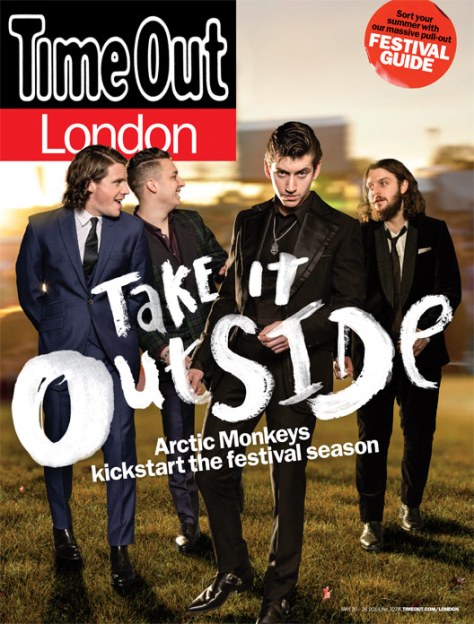

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

I’m sat in a coffee shop just off Shoreditch High Street when Alex Turner walks in, removing a pair of Ray Bans as he steps through the door. Everyone here is far too cool to stare, but there are turned heads and lingering looks as he makes his way to my table. He doesn’t swagger or strut. He’s wearing a brown suede jacket and skinny jeans, but what sets him apart are the details: the dark quiff that could have been sculpted by the King himself and the insouciance that can only really come from having headlined Glastonbury twice by the age of 27.

Rudimental are four impossibly upbeat boys from Hackney who are the new kings of the all-night party anthem. Last year’s debut album ‘Home’ was packed with more bangers than a family-size toad in the hole, and it rightfully earned them three BRIT Award nominations: Best Group, Best Album and Best Single (for ‘Feel the Love’).

Rudimental are four impossibly upbeat boys from Hackney who are the new kings of the all-night party anthem. Last year’s debut album ‘Home’ was packed with more bangers than a family-size toad in the hole, and it rightfully earned them three BRIT Award nominations: Best Group, Best Album and Best Single (for ‘Feel the Love’).

‘It’s got lust and love and danger and jealousy on it. It feels “red”.’ Sadly, Katy B is not talking about the Big Red pizza bus where we’re sat in Deptford. She’s describing her second album ‘Little Red’, the follow-up to her rave-igniting, Mercury Prize-nominated 2011 debut ‘On a Mission’. After digging in to a rocket-loaded Giardiniera pizza, the south London R&B icon opens up about dating, dancing and her past life as Peckham’s answer to Vinnie Jones.

‘It’s got lust and love and danger and jealousy on it. It feels “red”.’ Sadly, Katy B is not talking about the Big Red pizza bus where we’re sat in Deptford. She’s describing her second album ‘Little Red’, the follow-up to her rave-igniting, Mercury Prize-nominated 2011 debut ‘On a Mission’. After digging in to a rocket-loaded Giardiniera pizza, the south London R&B icon opens up about dating, dancing and her past life as Peckham’s answer to Vinnie Jones.