1. Party on, dudes

Holzmarkt, Germany

When Berlin’s fabulous open-air venue Bar25 closed in 2010, it was with a five-day party and a great deal of sadness. The club had helped rejuvenate a barren patch of industrial wasteland by the river Spree and it seemed inevitable that the now-prime real estate would be sold to investors.

Except, the story didn’t end with the sprouting of luxury high-rises. Instead, the land was leased back to Bar25’s owners, who set about envisioning a collectivist utopia – the perfect society in microcosm – on the riverbank where East Germany once met West. It would be a place where anyone could contribute and feel well looked after in return, where the planet’s resources and wildlife would be preserved, and where the party wouldn’t have to stop.

It took Juval Dieziger and Christoph Klenzendorf eight years but finally, this spring, their dream became reality with the opening of Holzmarkt. At first glance it’s simply the site of a great riverside bar, Pampa, and a club, Kater Blau, with an onsite restaurant, Katerschmaus – all popular with locals. But look beyond the beers and music, and you’ll find a ramshackle urban village, built out of wood and recycled materials, and hiding a nursery, doctor’s surgery, children’s theatre and cake shop. If you have some form of expertise – from medical knowhow to circus skills – Holzmarkt is the place to barter with it.

“Holzmarkt wants to attract people from all over the world and delight, inspire and connect them,” say the founders. “Here, they will find peace and fun, work and entertainment… For us, sustainability and change are not a contradiction.” The 12,000sqm site has four entrances and no gates. It’s open to all, even animals, with specially designed riverbank portals for use by beavers, ducks and otters. “Jointly, citizens and the city have won,” the owners add. “Holzmarkt will be a sanctuary for humans and beavers alike.”

2. Embrace woolly ideas

Lammas, Wales

“It’s totally possible to live a first-world lifestyle without it costing the Earth,” says Tao Wimbush, one of the founders of the Lammas Ecovillage in Pembrokeshire. His statement’s true in both senses – since 2009, Wimbush’s comfortable existence has been as cheap as it is sustainable.

Lammas is ‘off-grid’, meaning members of this pioneering community create their own power and rely on their skills to solve problems. Not that there are many within this lush enclave on the UK’s western edge. Happy cows chew the cud, the soil bursts with fresh produce and beautiful houses spring up without the help of any big development companies.

“In the village, we’ve all got computers, internet, washing machines, stereos…” Wimbush points out. The difference is that residents know exactly how much of the community’s solar and hydroelectrically generated power each appliance needs. “I’ve got two teenagers and they know that when they turn on their hairdryer it’s going to take 900 watts of power, so they check it’s available before they turn the hairdryer on. If it’s not, they can reroute power by turning off other appliances.”

Eating organic isn’t an optional luxury, it’s a necessity and houses are literally packed with natural materials. “We insulate our homes with sheep’s wool. It came straight off the sheep’s back and into a cavity in our timber-framed house,” says Wimbush. “We’ve proved that it’s totally possible to build affordable, healthy, high-performance houses with local, naturally available materials. The house I’m living in cost £14,000 [€16,000] and is more effectively insulated than the average suburban home.” It goes to show: it’s better to keep a sheep than be one.

3. Put your art into it

Christiania, Copenhagen

Pothole repairs are an issue that all towns face, but a workaday chore? Not in the ‘free town’ of Christiania. The autonomous neighbourhood in Copenhagen is famous Europe-wide, not least for its relaxed approach to cannabis, but also for its louche and lovely aesthetics. Here, potholes are as likely to be filled with marble mosaics or glazed tiles as asphalt.

“Beauty is just as important as function,” says Britta Lillesøe, an actress and the chairwoman of the Christiania Cultural Association. “Christiania is a town for people expressing themselves artistically in everyday life.”

Ever since it was founded as a squat in 1971, Christiania has attracted those who don’t feel they fit in anywhere else. “We accept and tolerate deviant ideas and behaviour, because we know that by judging others we judge ourselves,” says Lillesøe. “Being different is a way to be yourself.” However, those differences have a way of binding people together – forming what she calls an ‘urban tribe’. “Individualism and collectivism come together in the tribal spirit, which is beyond the political,” she says. “It honours tradition and yet despises worn-out ways. We are a bridge between the prehistoric and the future, between the shamanistic vision and the age of Aquarius.” Couldn’t have put it better myself.

4. Don’t stop till you get enough

Marinaleda, Spain

In 1979, 2,500 labourers in Andalusia found they had no land, no prospects and nothing left to lose. All around them they saw fields that weren’t being farmed and they decided to act.

It took 12 years of relentless protests, including whole-village hunger strikes, occupations of the farmland they were demanding and a march to the Andalusian capital, Seville, but by the turn of the 90s, the battle had been won and the land around the village of Marinaleda was handed over.

“Eventually, the local government decided it was more trouble than it was worth, bought the land from a duke and gave it to the people,” says journalist Dan Hancox, whose book The Village Against the World details the labourers’ struggles. During the almost three decades since, the people of Marinaleda have created their own narrative. “They have their own TV channel and radio station, which might sound ridiculous for a village of 2,500 people, but that’s what makes it fascinating,” says Hancox. “They party together at their own feria [festival] in July, which always has a revolutionary theme – one year it was Che Guevara. The village even has its own colour scheme: green for their rural utopian ideal, red for the workers’ struggle and white for peace.”

Che would surely approve.

5. Make love not war

Metelkova, Slovenia

The army barracks in the centre of Slovenia’s capital, Ljubljana, have not historically been the sort of place you’d want to spend a night on the tiles. Built by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 19th century, they have at various times been home to soldiers from Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and the authoritarian Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, none of whom were renowned for being much fun at the disco – which explains the glorious irony that since 1993 the barracks have been transformed into Metelkova, a home for artists and one of the most successful urban squats in the world. Moreover, the alternative city-state was home to Ljubljana’s first gay and lesbian clubs – Klub Tiffany and Klub Monokel respectively – and has since been used as a base for a whole variety of campaigns against racism and other forms of abuse. Even the mayor of Ljubljana, Zoran Janković, has been won over by the squat.

“Metelkova is a centre of urban culture,” he said in 2015. “It’s a place for critical reflection, civic engagement – and with its activities, it is establishing Ljubljana as an area where ideas of all generations can freely flow.”

If former Nazi army bases can become beacons of hope and togetherness, surely anywhere can.

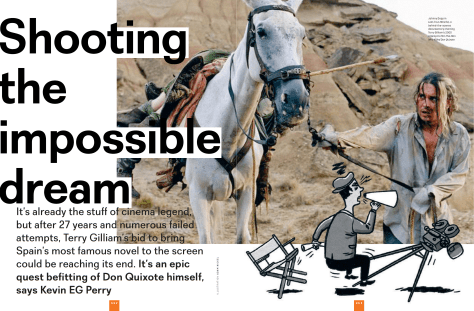

There are dark storm clouds gathering… F-16 fighter jets boom overhead, the thunderous sound of their engines interspersed with all-too-real thunderclaps. Johnny Depp is locked in a chain gang, scuttling sideways across the stark desert of the Bardenas Reales, in north-eastern Spain, but the microphones can’t pick up what he’s saying over the noise. The group approach the veteran French actor Jean Rochefort, poised atop a horse that refuses to move even when a member of the film crew gives a weighty push to its buttocks. Rochefort shifts uncomfortably in the saddle, feeling pain shoot through him from a herniated disc in his back. Finally, the storm breaks. It’s the only thing on this film set working on cue. As the rain lashes down, transforming the desert into a pit of quicksand, the director tilts his head back and roars into the heavens. “Which is it?” Terry Gilliam demands of the storm, “King Lear or The Wizard of Oz?”

There are dark storm clouds gathering… F-16 fighter jets boom overhead, the thunderous sound of their engines interspersed with all-too-real thunderclaps. Johnny Depp is locked in a chain gang, scuttling sideways across the stark desert of the Bardenas Reales, in north-eastern Spain, but the microphones can’t pick up what he’s saying over the noise. The group approach the veteran French actor Jean Rochefort, poised atop a horse that refuses to move even when a member of the film crew gives a weighty push to its buttocks. Rochefort shifts uncomfortably in the saddle, feeling pain shoot through him from a herniated disc in his back. Finally, the storm breaks. It’s the only thing on this film set working on cue. As the rain lashes down, transforming the desert into a pit of quicksand, the director tilts his head back and roars into the heavens. “Which is it?” Terry Gilliam demands of the storm, “King Lear or The Wizard of Oz?” The first disaster struck quickly, when Eberts’s promised $20 million fell though. It would be 11 years before filming began, a period in which Gilliam made The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys(1995) and Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas (1998). It was on the latter that Gilliam believed he’d found his leading man. After his Gonzo odyssey as Raoul Duke, Johnny Depp was lined up to play Grisoni. His then partner, Vanessa Paradis, was cast as his love interest and Rochefort was Gilliam’s Quixote. With Depp as the lead, the film secured a budget of $32.1m and began shooting in Spain.

The first disaster struck quickly, when Eberts’s promised $20 million fell though. It would be 11 years before filming began, a period in which Gilliam made The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys(1995) and Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas (1998). It was on the latter that Gilliam believed he’d found his leading man. After his Gonzo odyssey as Raoul Duke, Johnny Depp was lined up to play Grisoni. His then partner, Vanessa Paradis, was cast as his love interest and Rochefort was Gilliam’s Quixote. With Depp as the lead, the film secured a budget of $32.1m and began shooting in Spain. Working together, the pair have raised a budget of €17m and secured what Gilliam calls “the perfect cast”. He says lead Adam Driver is “the first actor involved in this project who’s actually reading the book”, while adding, “Thank God for Star Wars”, for transforming the former Girls actor into a bankable leading man. He adds that Palin will be ideal for Quixote because, while the character is “old, ridiculous, foolish [and] a pain in the ass… You’ve got to love him…”.

Working together, the pair have raised a budget of €17m and secured what Gilliam calls “the perfect cast”. He says lead Adam Driver is “the first actor involved in this project who’s actually reading the book”, while adding, “Thank God for Star Wars”, for transforming the former Girls actor into a bankable leading man. He adds that Palin will be ideal for Quixote because, while the character is “old, ridiculous, foolish [and] a pain in the ass… You’ve got to love him…”.

While the island’s unique geography is part of its draw, the country also has a busy cultural calendar. Here, its small size is a definite advantage. Halla Helgadóttir, who runs Iceland’s design week in March, says that designers from a variety of disciplines come here to share ideas; while Stella Soffía Jóhannesdóttir, of the Reykjavik International Literary Festival, tells an anecdote that illustrates just how intimate their events are. “When David Sedaris spoke here, he said he was used to audiences of 3,000. Here, he spoke to 100 people,” she says. “That makes our festival an opportunity to meet your favourite authors in very unusual circumstances.”

While the island’s unique geography is part of its draw, the country also has a busy cultural calendar. Here, its small size is a definite advantage. Halla Helgadóttir, who runs Iceland’s design week in March, says that designers from a variety of disciplines come here to share ideas; while Stella Soffía Jóhannesdóttir, of the Reykjavik International Literary Festival, tells an anecdote that illustrates just how intimate their events are. “When David Sedaris spoke here, he said he was used to audiences of 3,000. Here, he spoke to 100 people,” she says. “That makes our festival an opportunity to meet your favourite authors in very unusual circumstances.”