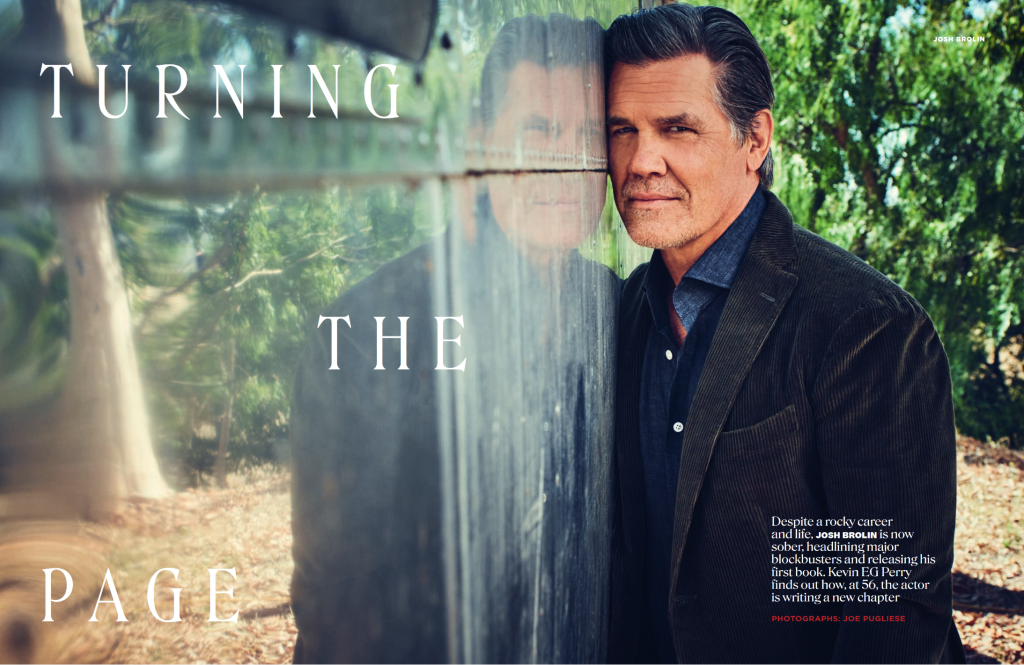

Josh Brolin slows his big black pick-up truck to a crawl as soon as he spots the injured deer on the mountain road ahead of us. He gives the wounded animal a wide berth and pulls up alongside a sheriff already on the scene, exchanging a few words of concern and expressing brotherly solidarity with the lawman’s watchful task. A moment later we pull away, continuing our winding descent from the remote Malibu film ranch where the 56-year-old has spent the morning being photographed for the cover of this month’s Vera. For the first time in the few hours we’ve spent together, Brolin falls into a contemplative silence.

The Oscar-nominated star of No Country For Old Men and Avengers: Endgame may have inherited his surname and his good looks from his TV-famous father, James Brolin, but he wasn’t born into a movie career. Rather than spending his childhood amid the glitz and sheen of Hollywood, Brolin grew up with dirt under his fingernails on a ranch outside Paso Robles, several hours north up the California coast, where his fierce and unpredictable mother Jane Cameron Agee kept a sort of menagerie.

“Whether I was birthing mountain lions, or cleaning wolf cages, or feeding 65 horses at 5:30 in the morning at eight years old… it was a pain in the ass,” Brolin tells me with a grin that breaks through his powder-white goatee. “But I look back on it now and I’m happy. Once directed properly, it gave me the ability to face fear in a very productive way… like with writing this book.”

The book in question is From Under The Truck, Brolin’s soon-to-be-published memoir that’s about as far from a clichéd celebrity autobiography as you’re ever likely to lay eyes on. He calls publishing it: “The scariest thing I’ve ever felt in my life.” It’s a raw, surprising and deeply affecting work from a man who dreamed of being a writer long before he ever stumbled his way into his father’s profession. “It’s what I’ve always loved, number one,” he tells me earnestly about writing. “I’ve never not done it every day.”

From Under The Truck throws out conventions like chronological time to skip back and forth between tales of love and loss, professional victories undone by alcoholism, childhood trauma and drug-fuelled teenage escapades. There are skittering poems, romantic vignettes and keenly-observed dialogues that read like kitchen-sink dramas. At the heart of it all there’s Jane, a hard-drinking, rabble-rousing, larger-than-life character who preached the gospel of country-and-western and raised her son to be an ass-kicker in her own image before driving drunk into a tree and dying at 55. “I had no plan to write a book. I just started writing, and then when I finished I realised I was 55,” Brolin says softly. “I went: ‘Jesus Christ, I thought my mom was old when she died.’ I thought she’d lived a good, full life. I realised she was young, super young. There was a whole other life to be lived.”

Brolin’s own life is proof of the possibility of second acts, and even further reinventions beyond that. At 13 he was dropping acid in the Santa Barbara suburb of Montecito, a member of a punk rock surf crew known as the Cito Rats, watching friends die young and assuming a similar fate awaited him. When his mother predicted he’d follow in his father’s footsteps, he pushed back hard. “I don’t know if I’ve ever told anybody this,” he says, running a hand through his salt-and-pepper hair. “At one point she said: ‘You know you’re going to be an actor.’ I had no interest in acting. Zero. I didn’t care for what my dad did. It made him go away a lot. The fluctuations in money made no sense to me. I hated that she said that. It made me hate it even more.”

Things changed when he took a high school improv class. He liked making people laugh by transforming into someone else, liked having to think on his feet. When he was kicked out of home he went to stay on his dad’s couch. “I just started going on audition after audition,” he remembers. “Maybe the Brolin name made people curious, but I also know people tried to stop me getting jobs because I was Brolin’s son. The Goonies was like the 300-and-something audition. I went back in six times because they wanted to make sure I was right for that part.” He was, and a bandanna-wearing 17-year-old Brolin made his screen debut in the much-loved adventure classic in 1985. “It was a silver platter experience,” he says. “It was all downhill after that!”

Almost before he realised it, Brolin’s promising future was behind him. He followed the The Goonies with a string of forgotten, forgettable films. “What did I do after Goonies?” Brolin asks rhetorically. “I was in the business 22 years and nobody cared.” In the book, Brolin juxtaposes his memories of Goonies with his impressions of landing the lead role in the Coen Brothers’ Oscar-winning No Country For Old Men over two decades later. “Those are the two milestones,” he explains.

The role remade his career overnight. “Before No Country I wasn’t making any money,” Brolin says matter-of-factly, explaining he took up day trading to support his two kids from his first marriage to actress Alice Adair. “I was always a numbers person, the geek in school that would ask the math teacher for extra work, so I was good at it. I realised I was watching fear and greed, and success had everything to do with discipline. I made more money trading than I’d ever made from acting up to that point.”

After No Country, he had his pick of roles and specialised in deconstructing masculine archetypes. He earned an Oscar nomination in 2009 for rendering the “pathetic” Dan White sympathetic in Gus Van Sant’s Milk, and gave vivid life to the chocolate-banana-inhaling, hippie-stomping cop “Bigfoot” Bjornsen in Paul Thomas Anderson’s sublime stoner noir Inherent Vice. Days before shooting the latter, Brolin and his now-wife Kathryn Boyd were on a drunken night out in Costa Rica when a stranger stabbed him in the gut. Only the fluke that the blade went directly into the thick umbilical ligament around his belly button saved his life. “I’m not going to win the lottery,” he says, shaking his head with a laugh at his luck. “I just get to live.”

It was one of many moments that convinced Brolin, in 2013, that it was time to get sober. “I’m not proud of a lot of stuff I did,” he reflects. “I was pretty crazy back then. I was very reactive when I drank.” He recognised the darker sides of his mother’s character in himself, and realised he didn’t want his story to end the way hers had. “Having a mother like Jane was amazing, but it was also awful,” he says. “I don’t really wish that on anybody.” He wanted something different for his own kids. “It wasn’t necessarily a conscious choice, but it’s about breaking that chain. I think they thought: ‘He’s a good dude, but he’s crazy.’ That was the general perception. When I first got sober, Eddie Vedder said to me: ‘Surprise everyone with a happy ending.’”

So he did. There were the blockbuster roles as Thanos, the finger-snapping baddie bent on wiping out half of all life in the box office-conquering Avengers films, and meaty collaborations with Denis Villeneuve in the tightly-wound thriller Sicario and both instalments of sci-fi epic Dune. More importantly, for Brolin, there was the chance to prove himself the writer he’d always hoped to become. Along with the memoir he’s written a play, A Pig’s Nest, also partly inspired by his wild, wildlife-filled upbringing. Meanwhile, at home, he sees bright flashes of his mother’s sense of freedom in his two young daughters, whose toy unicorns and baby dolls are strewn colourfully around inside the

truck.

We’re finally nearing the base of the mountain. As we hit the layer of fog that lingers above the Pacific Coast Highway, our phones chirrup to life to let us know we’ve returned to the zone of phone reception. I tell Brolin he can drop me anywhere I can call a car, but he won’t hear of it. He’s already decided he’s driving me home himself, hours out of his way. Maybe because he can’t bring himself to leave me stranded on the roadside, like the deer up the mountain. Maybe because he hasn’t finished telling me about the surprise of a happy ending.

Right before his mother died, in 1995, he was visiting her at home when he found her crying in the kitchen. Not from pain, but from pride. She was developing a TV idea about animal rescues, and for the first time in her life felt she was being taken seriously. “Her whole life she had felt like the woman with the beard, the snake with two heads,” Brolin explains. “She was just opening up to the fact that maybe she wasn’t just a freak… and then she died. For me to live that out, and to get past my own reactive Cito Rat mentality… there was survivor’s guilt for a while, but now it’s up to me to celebrate every moment I get to keep going.”